There are times I read something on the internet and feel this immediate need to respond. I think we’ve all felt that way about topics we care about. Thus is created the comments thread, the message board, and other forms of abbreviated, often argumentative discussions. For me, I don’t always feel capable of forming my thoughts and reactions into a coherent text, especially in a way that avoids being combative (I really don’t want to be that way). So I save links and texts in hopes of later returning to them and making some grand statement, some coherent argument, some well thought out response. But waiting for that time to come is often counter-productive as sometimes making the incoherent statement and getting feedback is where the real discussion and learning comes from.

Writing about the idea of comics and poetry has been on my to-do list for quite awhile. I’ve a note in Evernote from December of 2008 labelled “Comics as Poetry.” The note is just a bunch of collected links to people like Tom Hart, Bill Randall, and Gary Sullivan, all dating from early in 2008. I also have one paragraph of a started post from April 2011, and a never completed review of Warren Craghead’s How to Be Everywhere from February of 2011.

I feel strongly that there is a line of comics poetry that runs through the history of comics, but I always end up getting stuck on how to delimit such a feeling. What is comics poetry? What is poetry? Similar to asking “what are comics” or “what is literature” this is rarely the most productive place to start… and thus, the not starting.

What started me up again this time were two recent articles on the topic: Steven Surdiacourt’s “Graphic Poetry: An (im)possible form?” at Comics Forum and an interview with Bianca Stone at The Comics Journal from this past week. Both immediately set off my desire to respond.

First off, Surdiacourt’s article starts with the term “graphic poetry” which I find unfortunate. I can see the desire to parallel the “graphic novel,” (which he explicitly uses in one definition: “graphic poetry is to the graphic novel, what poetry is to prose”), but I don’t think it is a good idea to work from an already contentious misnomer of a term. Also, “graphic poetry” sounds like something a person in the 1950s would have used to describe “Howl.” Don’t let the children read that graphic poem.

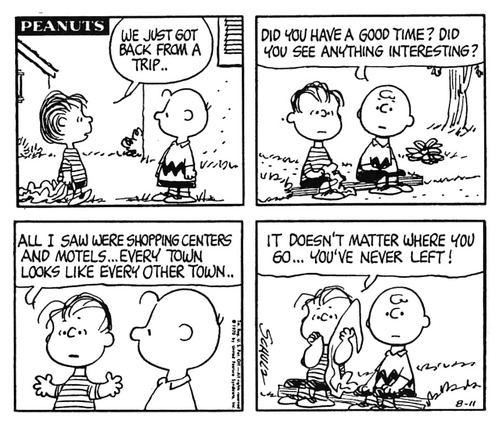

Surdiacourt’s text itself starts off on good footing, discussing the inspiration for the article: an exhibit that featured paired up collaborations between comics artists and poets. He immediately notes the tendency to have the artists illustrating poems, rather than the two truly collaborating. We’ve seen this before with the work published by the Poetry Foundation (here’s the last one in the series with links at the bottom to the others) under the rubric of “The Poem as Comic Strip” (that title alone tells you something). What we find there is a bunch of comic artists (some, like Ron Regé Jr., whose regular work is often comics poetry) illustrating poems by famous poets. It’s quite reminiscent of that bastion of comics greatness Classics Illustrated and not particularly inspiring (see Bill Randall’s column about the series). Of course, this model works for people in the poetry world because it maintains the integrity and primacy of the original poem/words.

Back to the essay at hand, it draws heavily on an article by Brian McHale about narrativity and segmentivity (I’ve only managed to read sections of it via Google Books which seems to cleverly only skip the pages where the primary analysis is done). McHale starts with poetry but turns to comics, spending the majority of the article discussing Martin Rowson’s adaption of Eliot’s The Wasteland as way to compare the two forms’ use of segmentivity and narrativity. Surdiacourt summarizes McHale’s theory:

…this segmentivity is defined as “the ability to make meaning by selecting, deploying, and combining segments” (Rachel Blau DuPlessis quoted in McHale 2010, 28). It’s not merely their gapped nature that connects poetic texts and graphic narratives, but also their shared capacity to play off “segments of one kind or scale […] against segments of another kind or different in scale” (McHale 2010, 28). The best known example of this kind of poetic configuration is obviously the enjambement, a trope in which the grammatical unit of the sentence (measure) is disrupted by the unit of the verse (countermeasure). A similar textual device is used in comics to create or maintain tension by the interruption of the action (measure) at the end of the end of the right hand page (countermeasure). [DB: Those are his ellipses and references.]

Surdiacourt rightly notes that this single criterion is not enough to compare comics and poetry. So, he also (briefly) brings up poetic rhyme in comparison with visual rhyme, braiding, as well as Barthes’ hermeneutic code. All of these can be gappy aspects of comics. In McHale’s article he also briefly discusses film, comparing filmic cuts to poetic segmentivity and the gaps in comics, noting the tendency of classical Hollywood style films to make cuts/gaps as invisible as possible (though one can argue against that when there is a desire to provoke mystery or suspense) in contrast to an Eisensteinian montage where gaps are introduced to force viewers to “make meaning.” I think the latter use of gaps is one place where comics can foreground their constitutive elements (images in sequence) in a similar way that much poetry foregrounds words and sounds.

Unfortunately Surdiacourt focuses on textual segmentivity, and his only example (from Nicolas Mahler) is primarily about the text. He ends on a strange note: “In the end, what and how graphic poetry can be (if it can be at all) remains to be imagined, and drawn of course.” He seems completely unaware of the existence of work that would fit his category, that would even better fit his category than his or McHale’s examples.

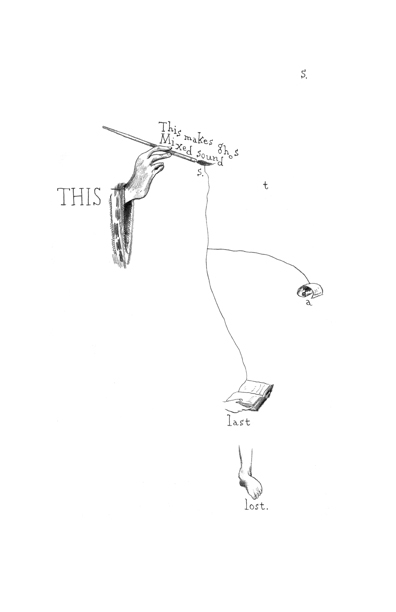

Certainly, looking at any comic by Warren Craghead provides a great example of segmentivity, a gappy aesthetic, and usage of various tactics Surdiacourt mentions. Craghead almost never uses text in the traditional way it is used in comics (balloons, captions), instead he fragments sentences and words into pieces (the word, the letter, respectively) and scatters them across the page. His pages and panels are also visually segmented as he tends to use images that are singular or partial–a single object, part of a larger object or scene–and then connect them visually through composition, lines, and text.

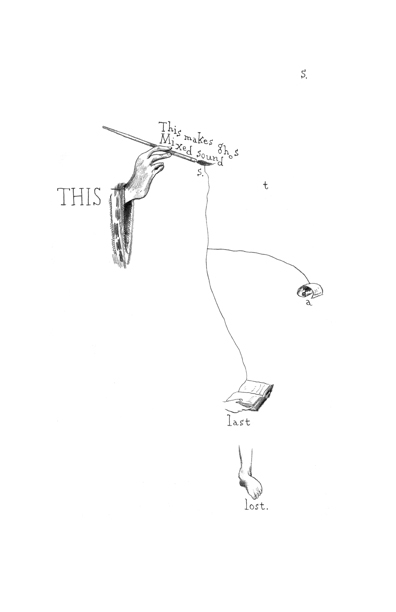

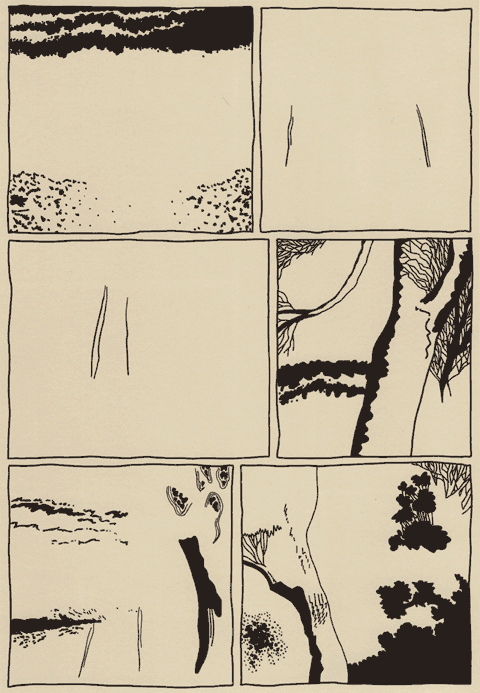

from Warren Craghead’s “This is a Ghost.”

For instance, this page from “This is a Ghost” shows a fragmentation of sentences, words, and imagery. The fragmentation creates a rhythm to the reading as one moves across the page through the multiple sizes and spacing of the text. You can note that the (admittedly out of context) sequence of images is not a “smooth” transition. Also, when read in full (see the references list below for a link to a pdf of the anthology), one finds a use of repetition (both word and image), braiding, and visual rhyme across the comic’s 14 pages. The comic tends to force a different type of reading than a conventional narrative comic that provides a very smooth and transparent reading. Craghead’s comic engenders a closer reading and a tendency to reread nonlinearly as one moves back and forth through the pages trying to decipher its layers (in a sense this echoes the hermeneutic code).

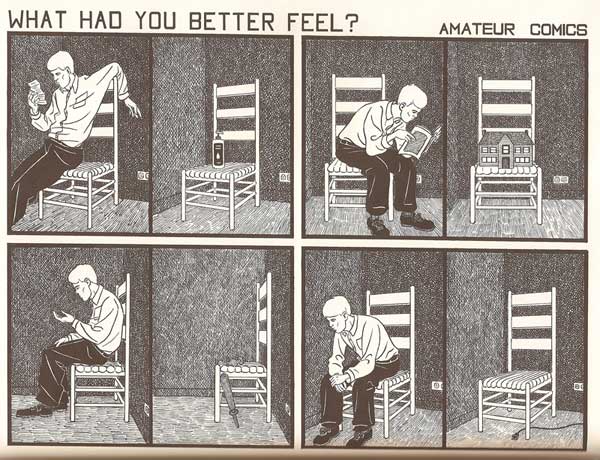

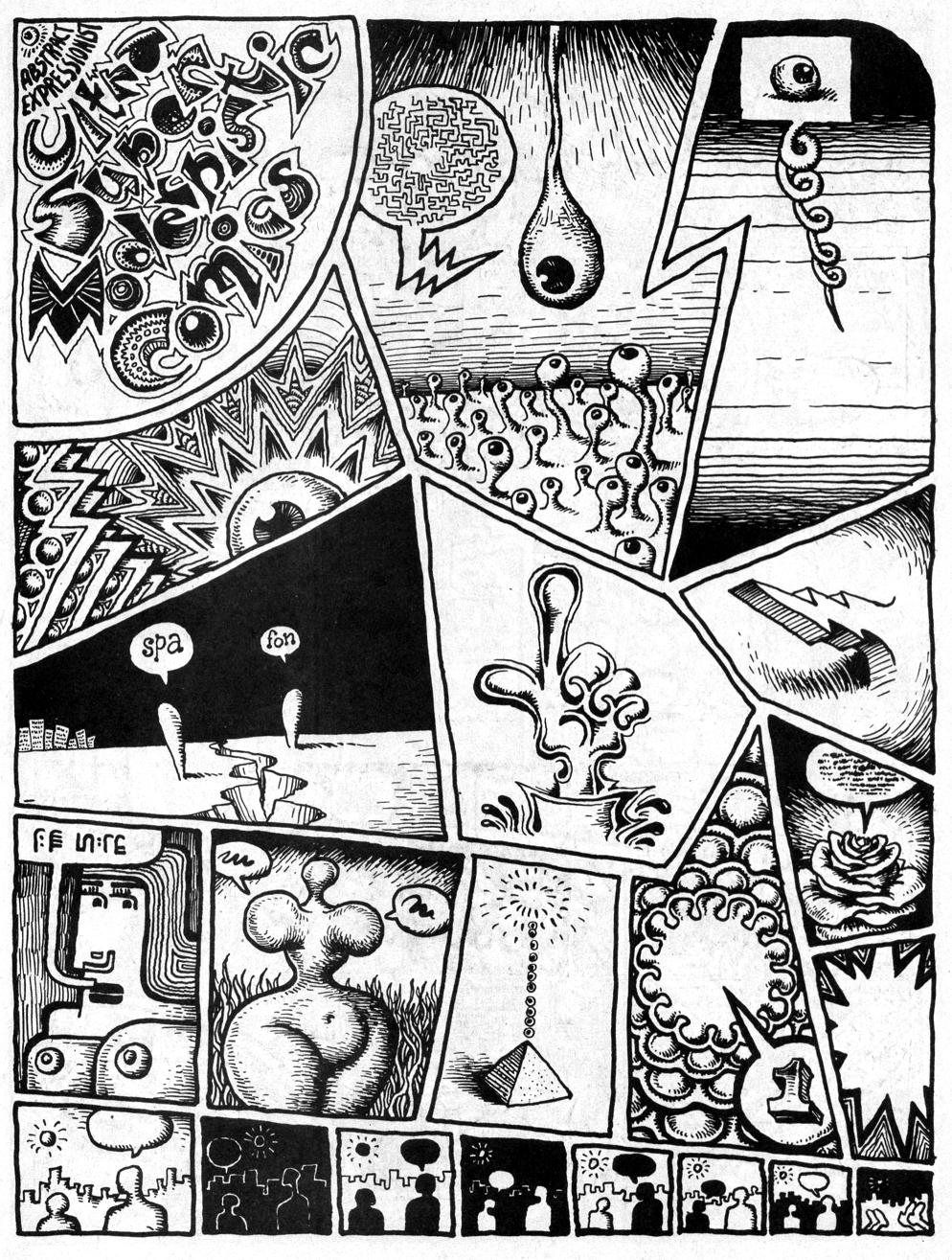

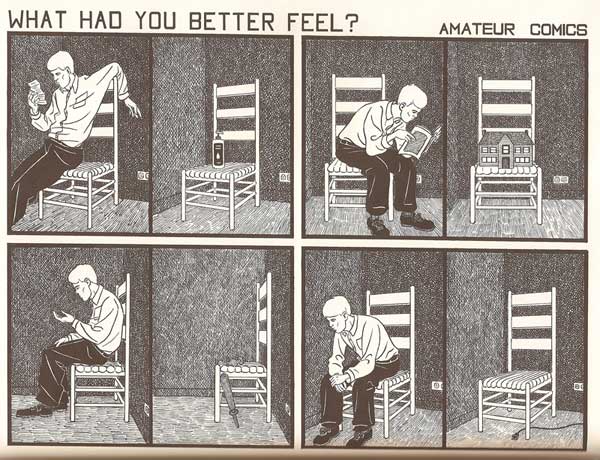

From John Hankiewicz’s “Amateur Comics.”

Much of John Hankiewicz’s work would also fit well as an example for Surdiacourt. For example, his “Amateur Comics” sequence makes use of segmentivity in an unusual way that could mirror McHale’s measure and countermeasure. Each page from the sequence is divided into four groupings of two panels. The groupings’ two panels are divided only by a single line, while the groups are divided by the negative space of the gutter. In most of the pages, the groupings divide up into a panel with a person in the left and one without a person on the right. The left and right also often show different views of the same scene, sharing view across all four groups. In this way, Hankiewicz disrupts one narrative sequence with another, creating a network of potential sequential and spatial readings of the 8 panels on the page. The spatial organization in conjunction with visual content, which at a general level shows alternating imagery, makes use of repetition and creates rhythm within the page and across the sequence of pages. Similarly the two lexias of text across the top of each image (a question beginning with a series of interrogative abverbs and a two word phrase in the form of “[something] Comics”) also form a consistent set of repetitions and variations that can be read across the pages. Without even discussing the specific content of the images, it’s fairly easy to see how one can read “Amateur Comics” as a form of comics poetry.

So, that’s just two artists off the top of my head, and neither are that obscure in the comics world. Both comics provide examples that are considerable more invested in the interaction of text and image in a “poetic” (let’s put my usage of this term aside for now) way than just the text by itself.

I wish that before he decided to posit something that he didn’t think existed, Surdiacourt would have looked for examples of that supposedly nonexistent thing. I’m sure if he looked around a bit he could have found some examples. Certainly, Rob Clough wrote about Hankiewicz’s work as “comics-as-poetry” in The Comics Journal (the online version is easily searchable), and there are often (mostly brief) examples to be found fairly easily.

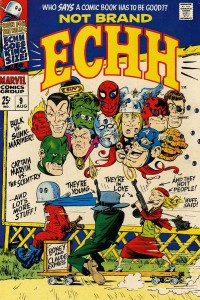

Bianca Stone, who explicitly calls her work “poetry comics” and edits a poetry comic column at The The, was interviewed in The Comics Journal and shows a similar lack of knowledge of artists working in the comics world. Stone’s foregrounding of “poetry” in her terminology does point to her grounding in the poetry world rather than the comics world, so that could be part of the reason (none of the comics she explicitly mentions are outside the mainstream (be it superheroes or “alternative”)). The interview bears this out as she discusses being in an MFA poetry program and not having much interaction with the comics world. (There are a bunch out us out here, Bianca.)

Even her definition of poetry comics points to a focus on text as poetry: “Sequential art that uses poetry as the text.” I realize she is surely simplifying here to have a quick definition, but the concept makes it seem like the work is “poetry + comics” a kind of addition wherein the comics–the images and the iconography and grammar of comics–is an add-on to the poetry, which is text. Some of the work she’s put in her column has born out this conception. To her credit, Stone’s work in her I Want to Open the Mouth God Gave You Beautiful Mutant doesn’t totally play out that formula, though I think it does come through stronger as a poem via the text.

For this reason, I use the term “comics poetry” as a way to foreground the comics aspect, a more succinct locution than Clough’s “comics-as-poetry”. Comics poetry isn’t poetry as text with comics images; it’s the whole comic as poetry. The images, the words, the structure, the rhythm, the page, all of it is used together to create the poetry, to create comics in a poetic register. But, as I mentioned in the beginning, this gets tricky, since “poetry” and “poetic” can mean a lot of things to different people.

In the end that doesn’t really help us identify or discuss how comics poetry differs from any other comics. So, I’ll take that up in part two (later next month), looking at how a few other people have discussed comics poetry or the poetic in comics, and then I’ll offer my own thoughts on the matter with some more specific examples.

References:

- Craghead, Warren. “This is a Ghost.” In Ghost Comics, edited by Ed Choy Moorman. Bare Bones Press, 2009. 151-164. Order the volume or read the pdf: http://edsdeadbody.com/barebones.html

- Dueben, Alex. “A Bianca Stone interview.” The Comics Journal. 24 Aug 2012. http://www.tcj.com/a-bianca-stone-interview/

- Hankiewicz, John. “Amateur Comics.” In Asthma. Sparkplug, 2006.

- McHale, Brian. “Narrativity and Segmentivity, or, Poetry in the Gutter.” In Intermediality and Storytelling edited by Marina Grishakova and Marie-Laure Ryan. De Gruyter, 2010. 27-48.

- Randall, Bill. “Deaf Ears: Poetry, Comics and the Poetry Foundation’s Comics Project.” The Comics Journal #288 (February 2008): 193-5.

- Stone, Bianca. I Want to Open the Mouth God Gave You Beautiful Mutant. Factory Hollow, 2012.

- Surdiacourt, Steven. “Image [&] Narrative #5: Graphic Poetry: An (im)possible form?” Comics Forum. 21 Jun 2012. http://comicsforum.org/2012/06/21/image-narrative-5-graphic-poetry-an-impossible-form-by-steven-surdiacourt/

A few more comic artists who might fit in this vein (for at least some of their work):

Julie Delporte, Oliver East, Franklin Einspruch, Allan Haverholm, Aidan Koch, Simon Moreton, Anders Nilsen, Jason Overby, John Porcellino, Alexander Rothman, Frank Santoro, Gary Sullivan, me, and surely others I am obviously forgetting.