Okay, I’ve just seen The Avengers, Marvel’s and Disney’ latest blockbuster superhero movie, and first I want to state: yes, Jack Kirby does get his name in the credits.

In a half-assed way.

The credit line states: “Based on the comic book by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby.”

True enough, as far as it goes. A more honest credit would have read: “The Hulk, S.H.I.E.L.D., The Avengers and Nick Fury created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby; Thor and Loki created by Larry Leiber and Jack Kirby; Black Widow created by Stan Lee, Don Rico, and Don Heck; Captain America created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby.”

(And justice would further be served by the additional line: “Iron Man created by Stan Lee, Larry Leiber, Jack Kirby and Don Heck; Hawkeye and the Black Widow created by Stan Lee and Don Heck.” Don Heck was never a fan-favorite, and has been dead for some years; there’s no constituency for his memory; but his contribution should not be slighted.)

The problem is, as the dominant paradigm now has it, individuals don’t create; only corporations create. And Marvel/Disney would rather slit their entire management’s throats than acknowledge that this fiction, the source of their billions, is based on a lie.

Well, I shan’t continue in my grumpiness — after all, I was hypocrite enough to ignore the boycott of the film initiated by Kirby family supporters such as Steve Bissette.

So how was the movie?

Alan Moore, when asked his opinion of the first Image superhero comics, made an interesting analogy.

He said an old-style superhero comic (say, a Dick Sprang ’50s Batman) could be compared to coca leaf: a mild stimulant. The powerful superhero comics of the seventies, like those drawn by Neal Adams, would be the equivalent of refined cocaine. And the Image comics were the equivalent of crack.

To steal his simile: The Avengers is the crack cocaine of superhero movies. It will stimulate the comics fan into a near-fatal geekasm.

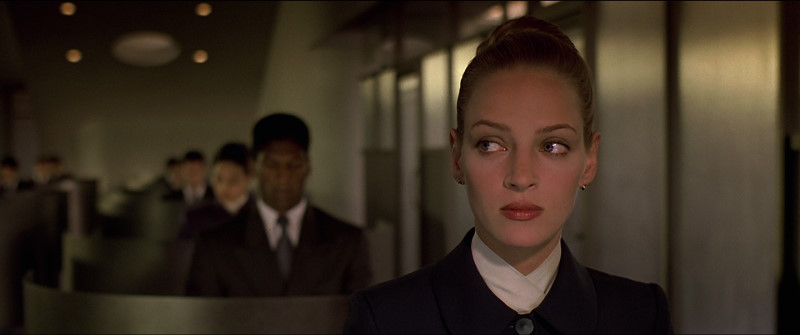

That’s not a criticism, actually; this flick’s an exceptionally well-made distillation of its genre. If you like this sort of thing, this is the sort of thing you’ll like, to quote Abraham Lincoln. It hits all the right notes. Superheroes beating the shit out of each other? Check. Cool, sexy super spy? Check. Neat-oh futuristic equipment and weaponry? Check (The rise of the Shield helicarrier from the ocean to the skies invokes genuine awe.) Nasty-ass aliens, supercilious super villain, awesome costumes (Loki finally gets to see action in his bitchin’ horned helmet), tons of death and destruction, and Cap instructing old Greenskin: “Hulk, smash!”? Check, check, check, check and check!

The film isn’t lacking in non-infantile pleasures, either. The dialogue is crisp and witty — although poor Thor and Captain America are handicapped by having to wax solemn or anguished while the rest of the cast are given all the zingers. The best lines go to Loki (Tom Hiddleston) and Tony ‘Iron Man’ Stark (Robert Downey Jr); one scene between the two makes one think more of Noel Coward than of Stan Lee.

(There are plenty of physical laughs, too, mostly coming from the Hulk. After an incredibly snotty divine put-down by Loki, Greenskin educates him with a beat-down that looks like a violent gag from a classic Popeye cartoon.)

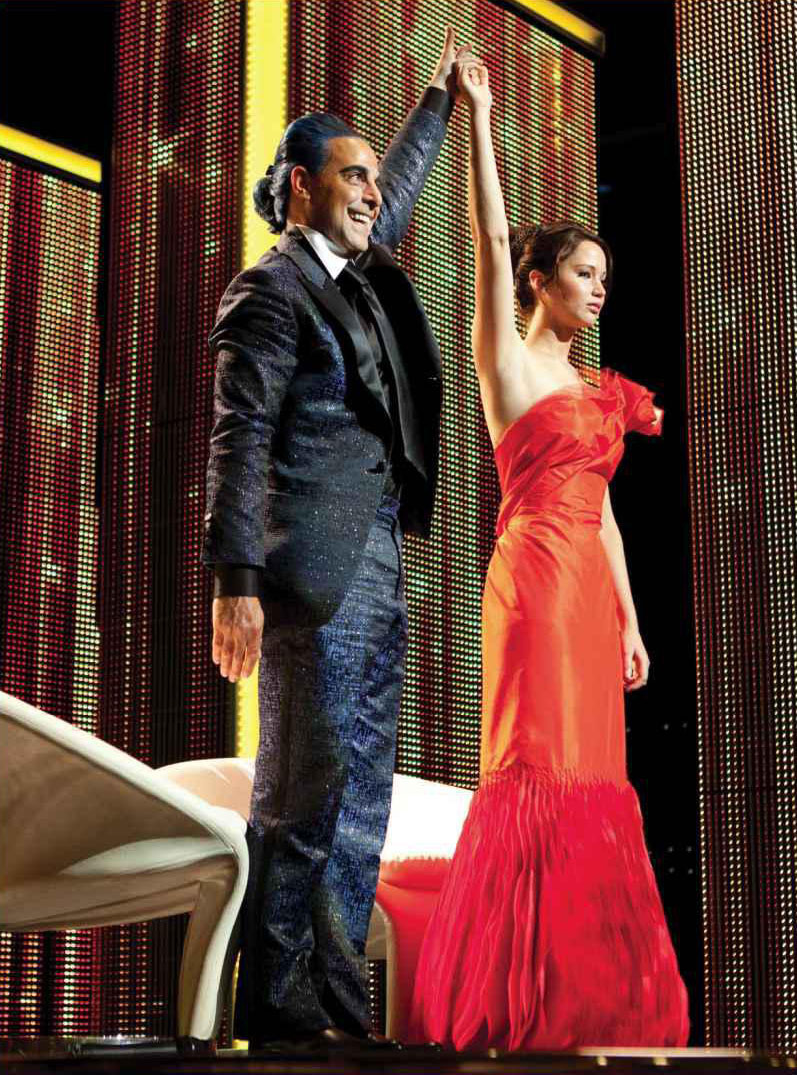

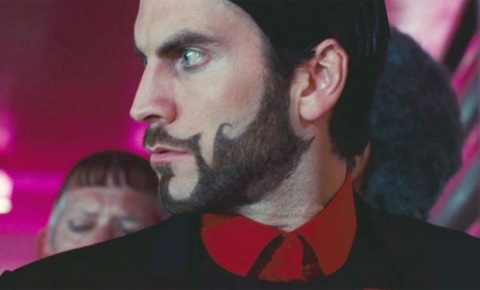

Ah, Loki. An adventure tale is only as good as its villain. The classically-trained British Hiddleston plays the part with such relish that one only sees in hindsight the nuances he brings to the character: there is an under-layer of pain and anguish to his posturing. And, true to both the comics Loki and that of Norse mythology, he relies as much on cunning and the psychological manipulation of his foes as upon brute force.

(I won’t tell why, but the funniest line in the film is Loki’s “I’m listening.”)

Downey somewhat unbalances the flick: as some wags put it, a better title would have been ‘Iron Man III, co-starring the Avengers’. Not that I’m complaining — it’s always a delight when he takes the screen, especially when out of armor.

However, Marvel showed great judgment when they chose Joss Whedon to direct. Whedon has extensive experience in comics and feature films, but I’d wager that he was chosen especially for his experience in television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, where he proved his ability to handle large ensemble casts in fantastic milieus. The script perfectly characterizes every role, far better and more subtly than the comics ever did. It’s a masterpiece of psychological clockwork.

Two of the minor heroes particularly stand out: Hawkeye (Jeremy Renner) and the Black Widow (Scarlett Johansson). There are hints of dark, complex, anguished pasts for both of them. I get the feeling Whedon would have been more than happy to have centered the film on these two.

One surprise, on the other hand, is how overshadowed Thor (Chris Hemsworth) emerges. Frankly, he cuts a poor figure compared to the dashing Stark, the brutish Hulk, the glittering Loki. In Thor, he towered; here, his cape looks tatty, and his previous vikingly cool beard makes you think now that he was too rushed to shave that morning.

The fights, the Hulk-smashing, the repartee are all top-notch. In sum, if you want a summer blockbuster where “you can check your brains in at the door”, this is for you.

But we never can do that, can we?

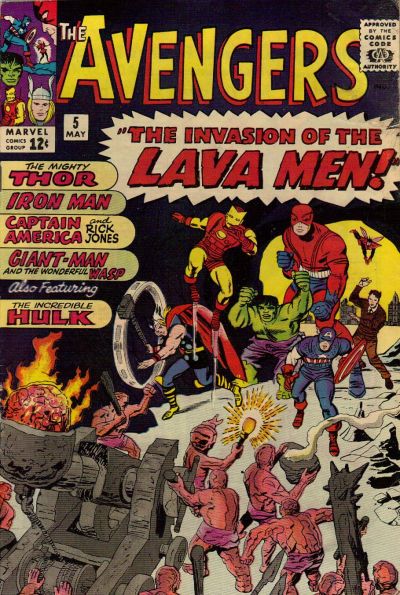

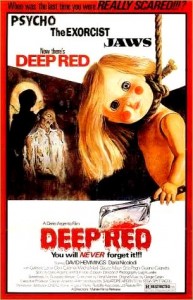

Art by Jack Kirby and Frank Giacoia

The Avengers has special place in my nostalgic pantheon: issue 5 was the very first Marvel comic I’d ever purchased, back in spring 1964, when I was 9 years old. Sure, I was aware of the marketing hook behind it — “Your favorite heroes TOGETHER!”– and didn’t care a whit. Yeah, I’d already seen it with Justice League of America from DC. Loved it there, too.

Looking back, there were troubling aspects to this comic. The Avengers were the élite, and pretty much also the tools of the élite. They were bankrolled by Tony Stark, comics’ epitome of the military-industrial complex; they lived in a mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York — the swankiest address in the world. ( Of the great mansions built there by the “robber baron” capitalists of the 19th century, only the one housing the Frick Collection remains.) They fought commies and aliens and worked with the government. And they were self-selected: the aristocrats of the superhero world.

They resembled nothing so much as an elite private club, like the Yale or Century clubs, floating high above hoi polloi.

The film carries this conceit to the next step, arguably an even more sinister one.

The last half-hour of the movie shows a gigantic battle between the Avengers and an army of extraterrestrial invaders in the streets of Manhattan. And my childish, fannish joy in these shenanigans was overlaid by a feeling of dread — of appallment.

I realized why halfway through: it was the location of this mass destruction that roiled me. A ten-year-old taboo had been shattered, one dating to 9/11. It’s now acceptable once more to depict buildings in New York, and the people inside them, being destroyed.

And this is where my unease was compounded. This iteration of the Avengers wasn’t the old “gentlemen’s club,” obnoxious though that be.

This one was conceived from the start as the auxiliary of a tremendously powerful secret American government defense agency. This élite cadre of superhumans, following the orders of a wise leader, Nick Fury, was there to protect us from unreasoning, fanatic aliens bent on flying into our greatest city and toppling its skyscrapers.

From Space Al-Quaeda.

So that’s my reading of The Avengers. Its subtext, hardly subtly advanced, is the glorification of Homeland Security and of the current security state. Why, even the Hulk, that powerful adolescent fantasy of revolt against authority, meekly goes along with the program. Who are we to gainsay him?

Hmm… maybe I really should’ve checked my brain in at the door. Then again, maybe I did, and just forgot to check it back out…

P.S. I saw this film in Paris, where it was released on April 25; it won’t be in general release in the States until May 5. Such divergences between international release dates are less common than they once were, for two reasons: a) the studios want to discourage piracy, and b) cultural globalisation. It’s only in the past twenty years that France adopted summer as a movie blockbuster season, as it has always been in America: before, summer was given over to b-films and re-releases. (Hey, if you were spending the summer in France, would you want to waste it in a movie theatre watching Hollywood fare?) And gone are the days as recent as 1989, when Warner Brothers had to launch a whole campaign in advance of the Tim Burton movie explaining who Batman was to the French. The crowd I saw Avengers with was wholly familiar with the characters. La coca-colonization culturelle n’est pas morte, helas!

Spoiler alert:

The usual post-credits closer reveals who Loki’s mysterious alien ally is. Yep, it’s Thanos.