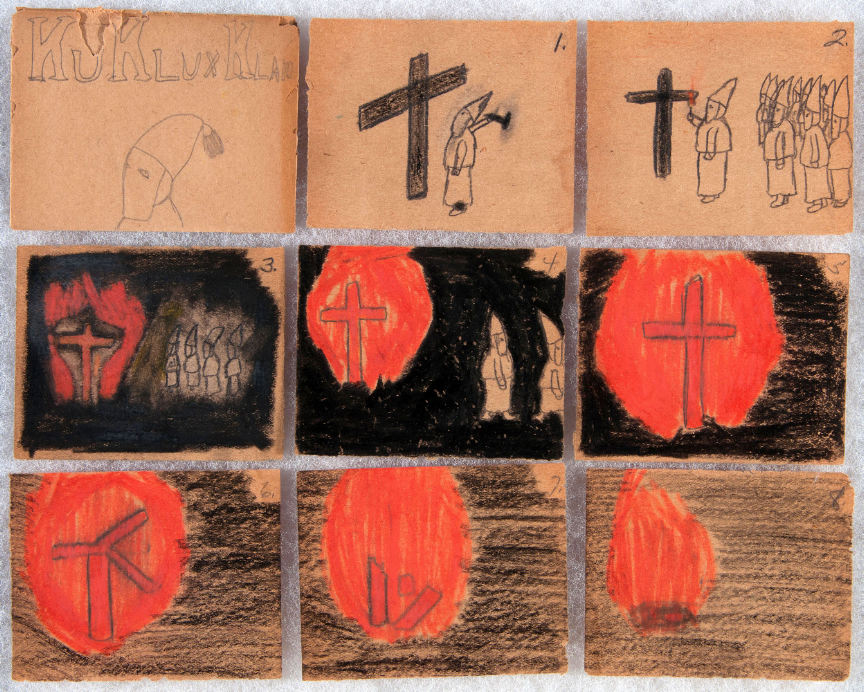

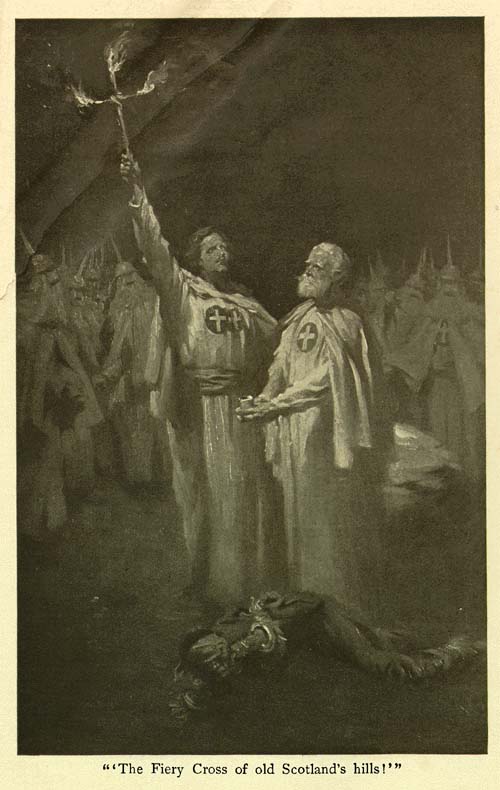

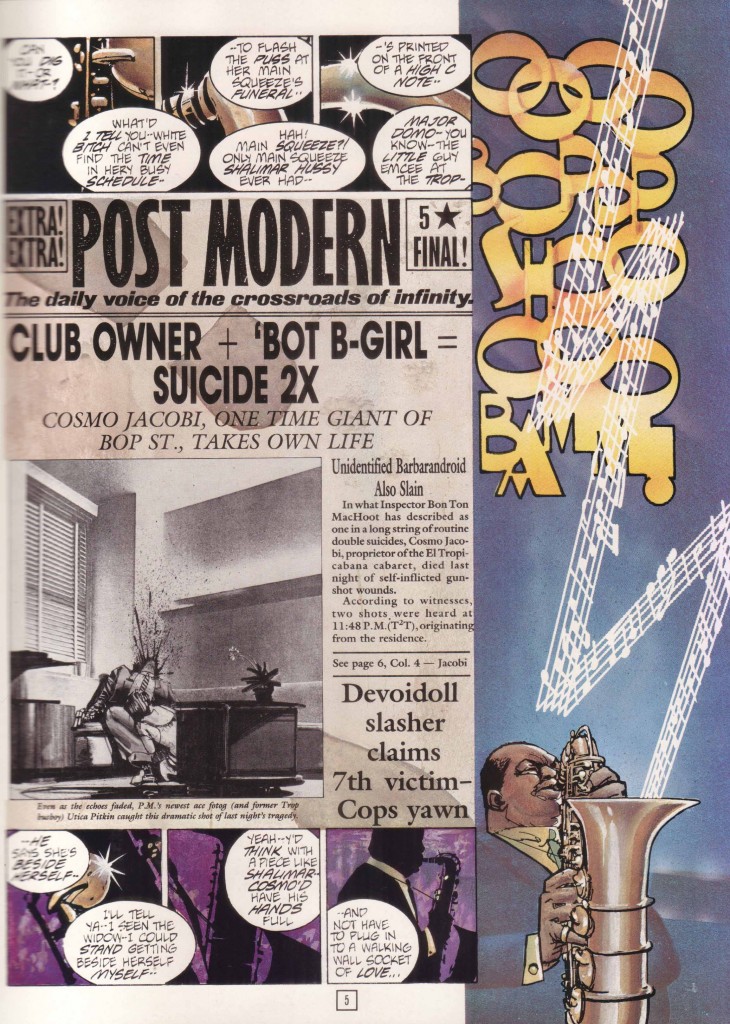

Frank Miller (c. 2016) is the Donald Trump of comics. Not merely because he’s demonstrated some ebullient racism, not because he really hates Muslims, not because of his warped ideas about women, but because of the general incoherence of his vision. The sad thing is that Miller considers Trump a bit of a “buffoon.”

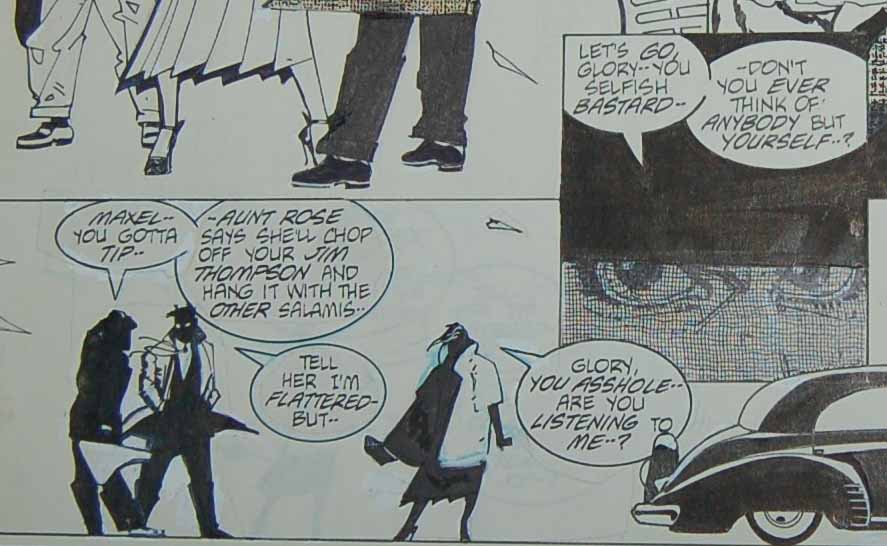

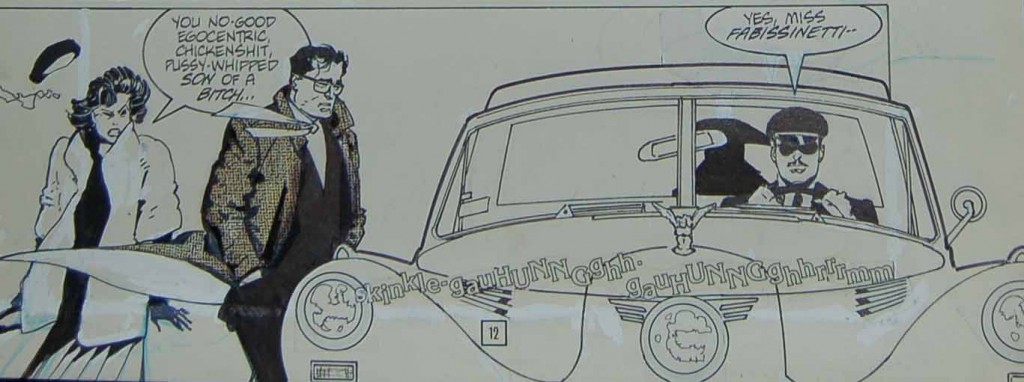

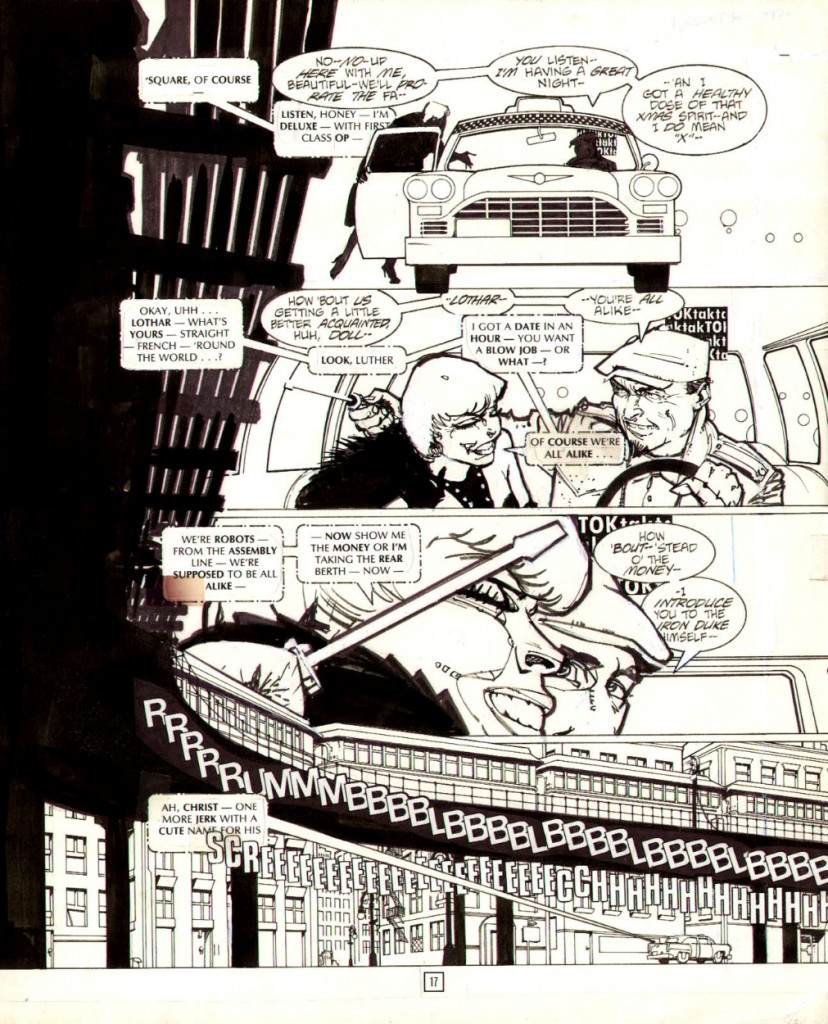

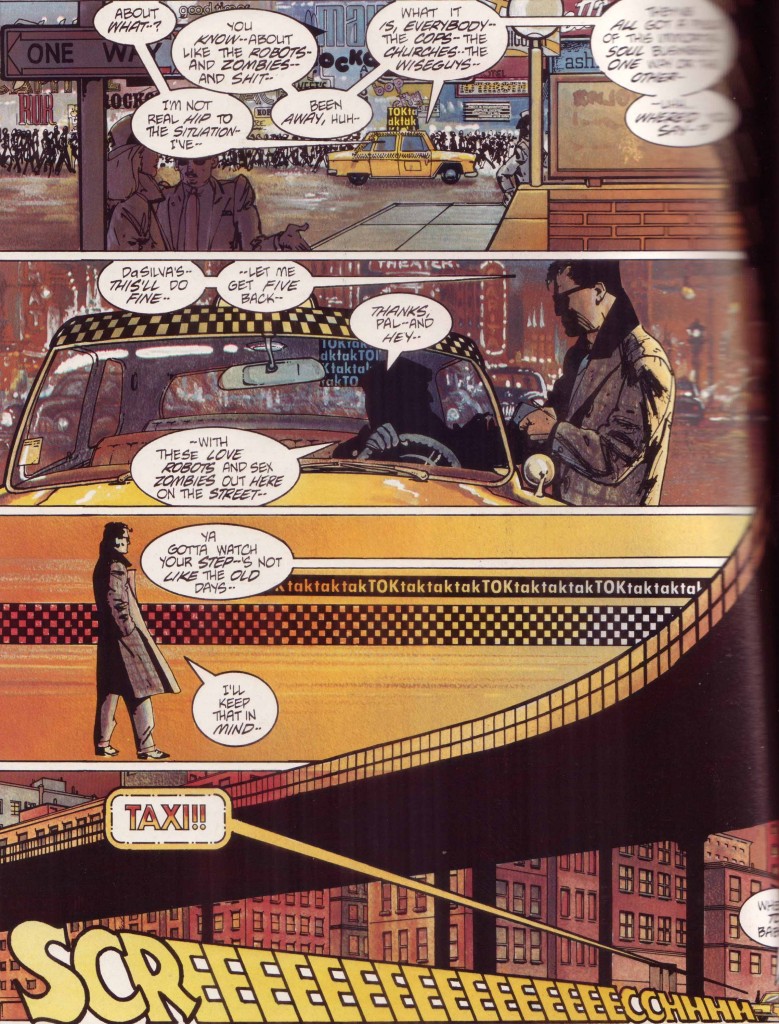

There’s a whole article to be written about Miller’s political beliefs from the 1980s to the 2010s: how a man who wrote a satire on Reagan and Nuclear Armageddon could transform (?) in latter years into such a reactionary (presumably he always was one); how an artist who created a comic about an all conquering female ninja and her masochistic, castrated male partner (he only gets an erection when he submits) could come to see women in latter years as harlots. I guess Freudians would put this down to a Madonna-Whore complex.

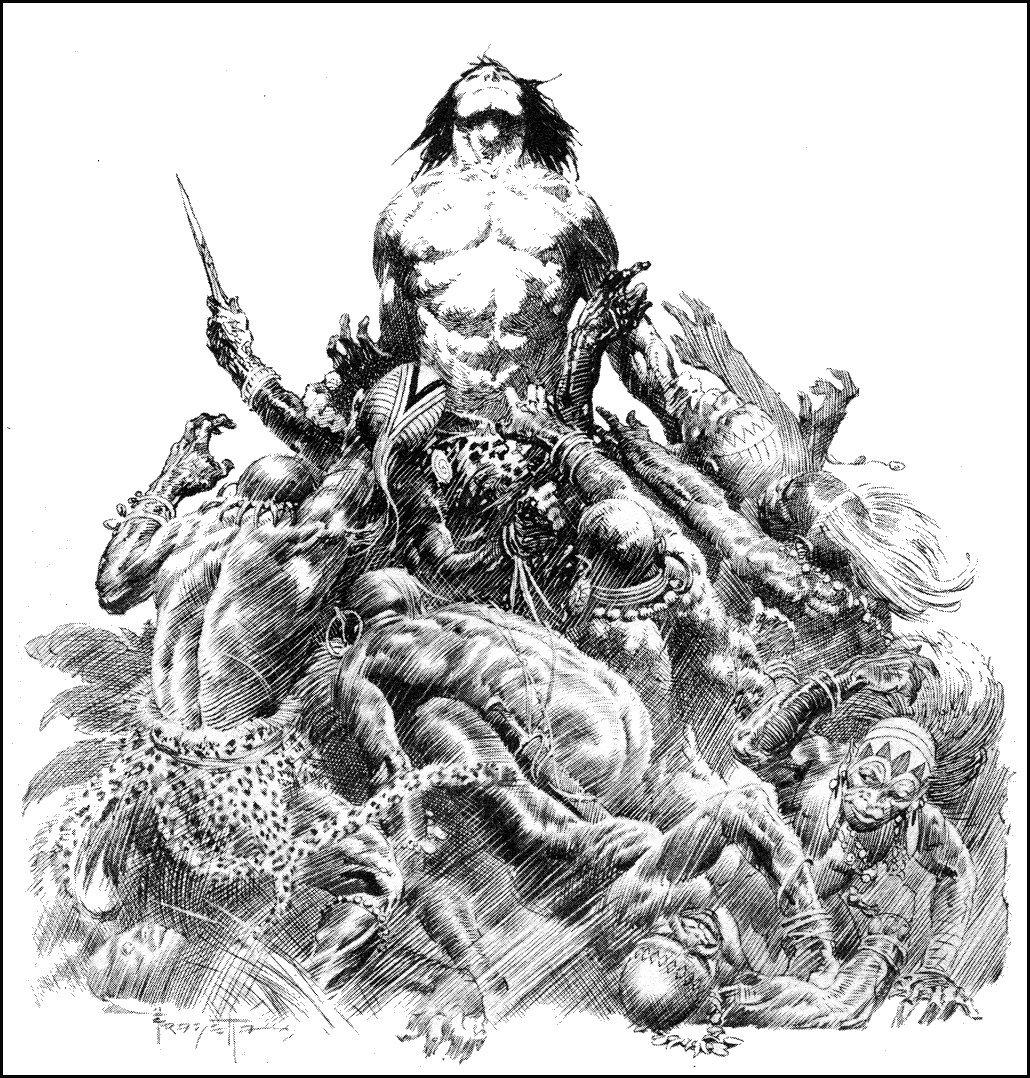

Frank Miller the thinker is a slightly knotty problem, but there’s nothing especially complex about the drawing hand of Frank Miller circa 2016. The one time master of dynamic movement and page composition has hit rock bottom and his fans aren’t amused.

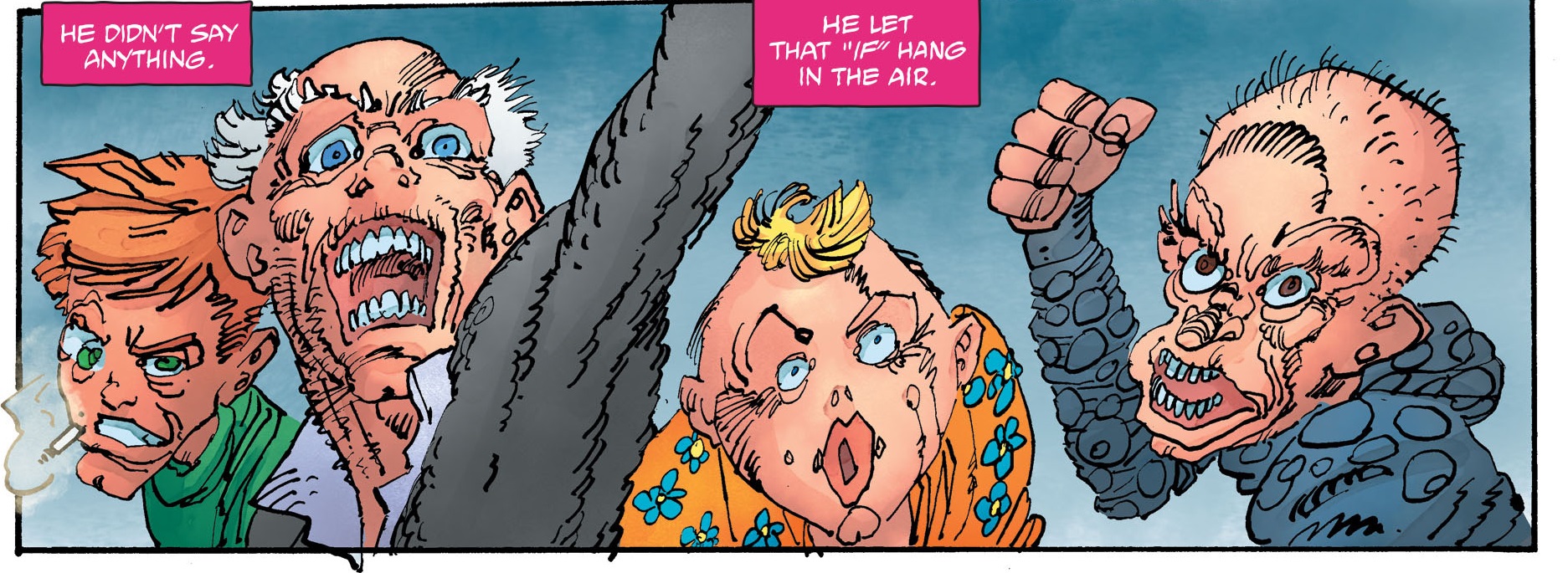

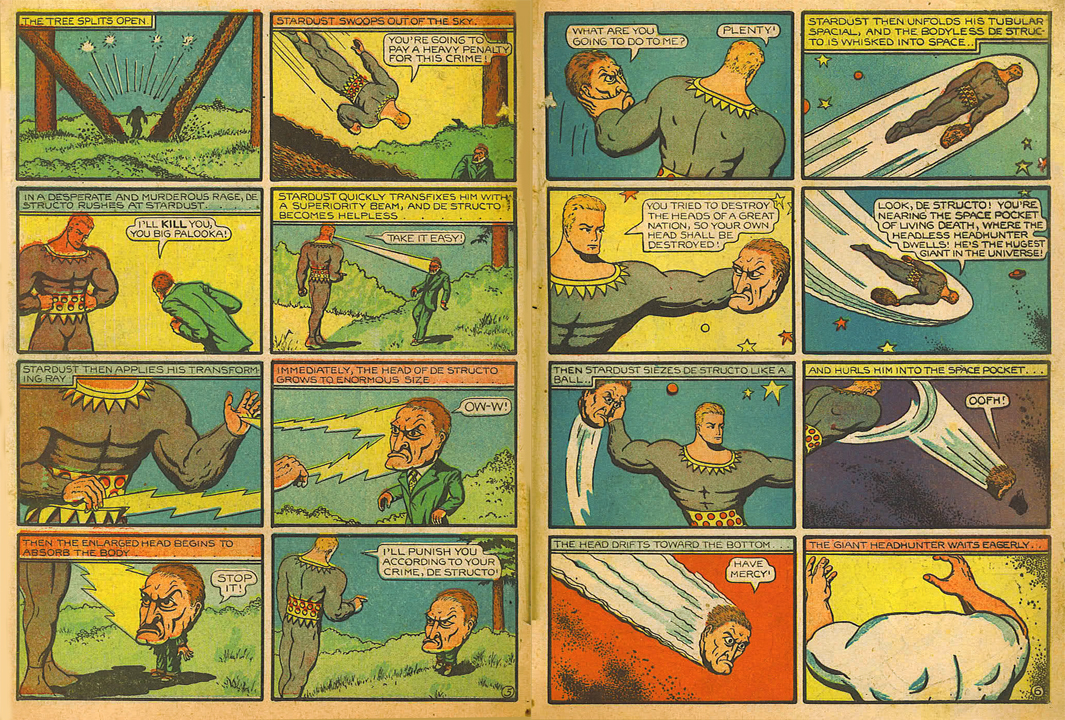

He has a 12-page back-up story in The Dark Knight III: The Master Race #4 which is little more than one big fight scene with some barely sketched out characters just limply hanging in blank space. Then Aquaman appears in all his shoddy glory and…the end. This is a rigorous reflection of the story in the main body of the comic which is also little more than an extended fight scene between Superman and his daughter, with Batman and Carrie Kelley as spectators. Remember the scene in The Dark Knight Returns where Batman beats Superman to a bloody pulp under some street lights like the lowlife street mugger he is? Well, the new comic is yet more fanservice for Batfans who think the Man of Steel sucks (Miller is the inspiration here, not the cause).

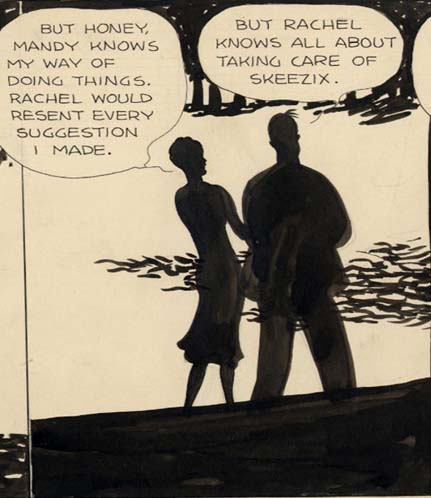

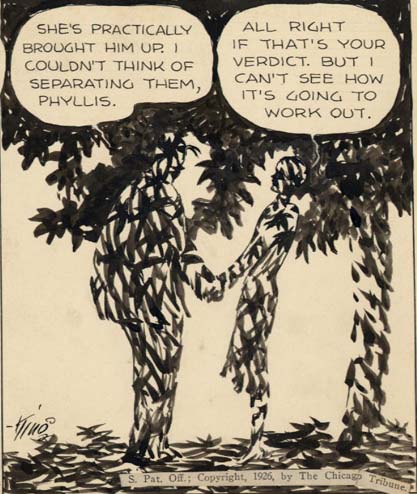

But it’s not all corrupt—if you take individual panels out of context you can still see some remnants of the old artist. A silhouette here and some adequate superhero posing there.

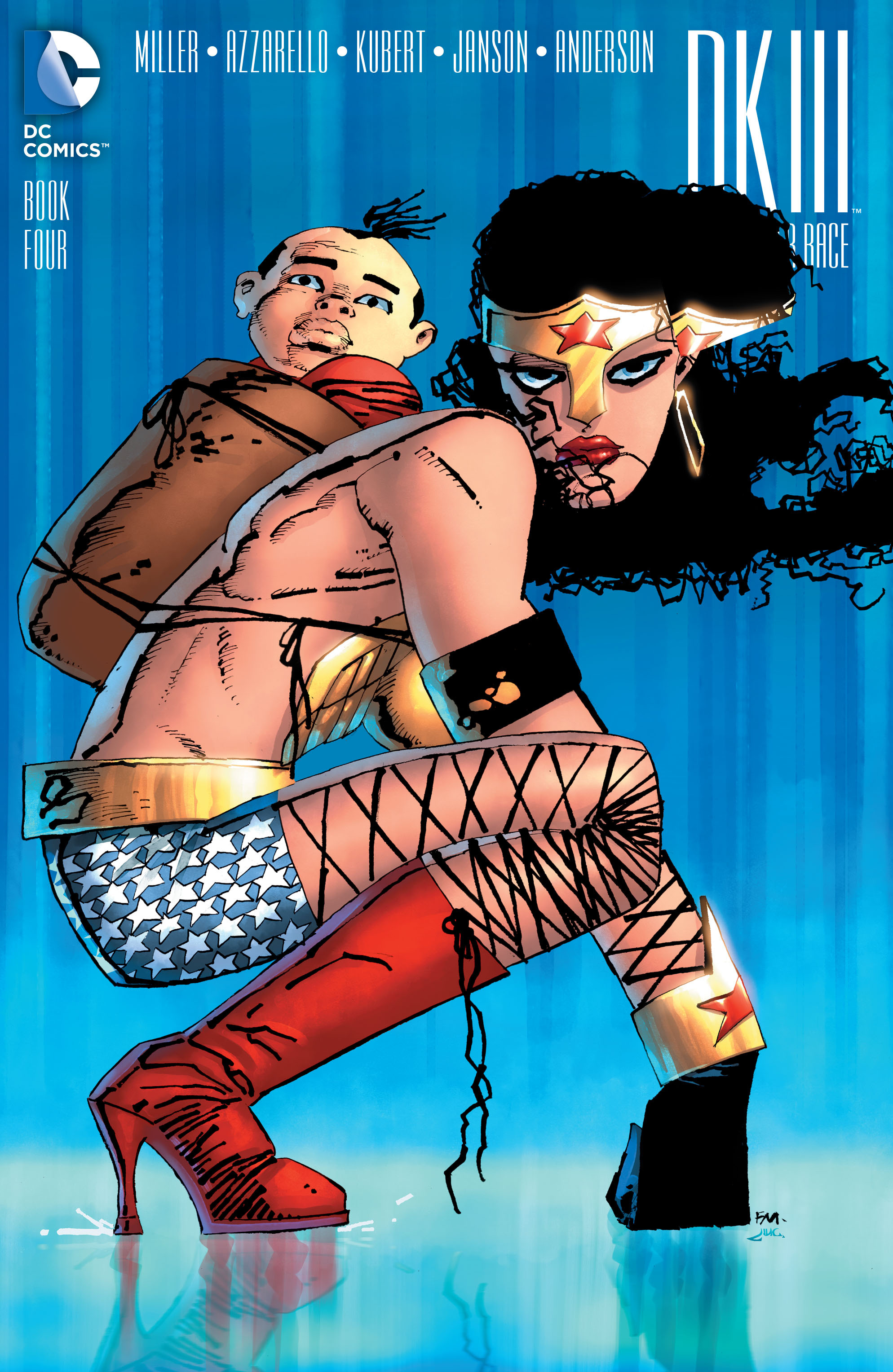

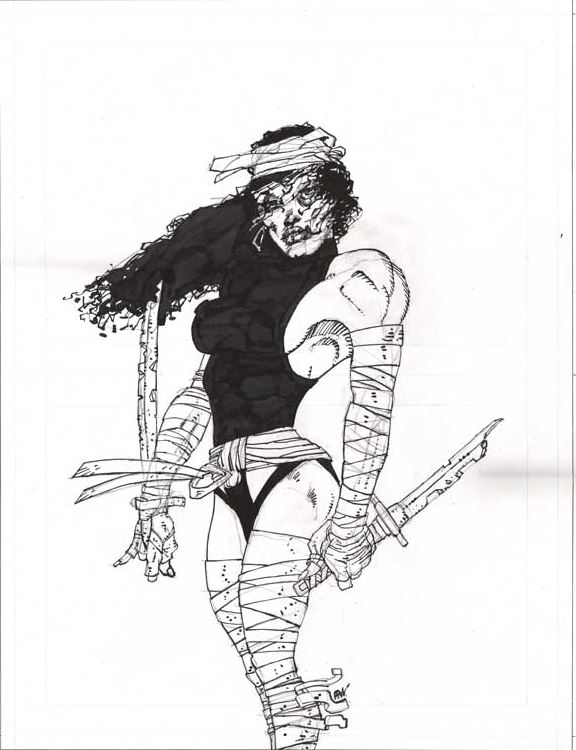

Still, no one really cares about Miller’s subliterate backup story; the internet is far more disgruntled by his series of covers for DC. The most recent culprit is his portrait of Wonder Woman for a DK3 #4 variant cover.

Yet for me, this seems closer to that time when Trump emerged from a relaxing spa a few months back and said that he would be friendly with Russia—which is infinitely preferable to World War 3 I should add.

Yes, she looks a bit sullen but not everything needs to be fun and games a la Marston and Peter. He’s on song again because of the nostalgia he has for the warrior-child motif from his days as a fan of Lone Wolf and Cub. The thing isn’t conventionally erotic or pornographic; this Wonder Woman doesn’t want to make love to you; she doesn’t even want to be tied up with her sorority girlfriends. She just wants to beat you up, hence the gorilla-like stance with her fists on the ground. The breasts are a wee bit big but they’re covered and it could just be the armor doing the talking. The bicycle shorts are cool and the stars quite well drawn. Anyone who knows anything about recent Miller will tell you that this is “decent” Miller as opposed to OMFG Miller. To wit:

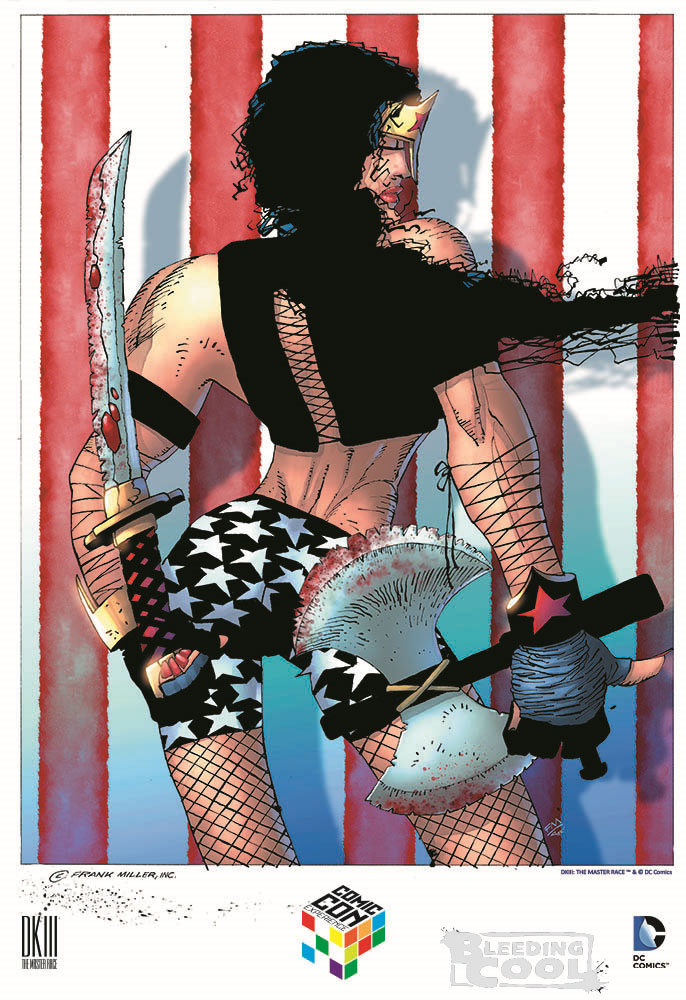

I will accept intimations that this image is a natural extension of Miller’s penchant for night spots of all sorts in his sequential work, and thus a homage to drag queen clubs; maybe a bad homage but a homage nonetheless.

Every few months, Miller releases his new modernist vision of superheroes to the world to the general consternation of the Twittersphere. And every time, one of these images appears, the internet expresses equal parts astonishment, outrage, and delight that something so grotesque should exist in this universe. It’s like stepping on some dog poo just as you’re about to get into work—you have to tell someone because it just stinks. If you don’t, they’ll find out and then where would you be?

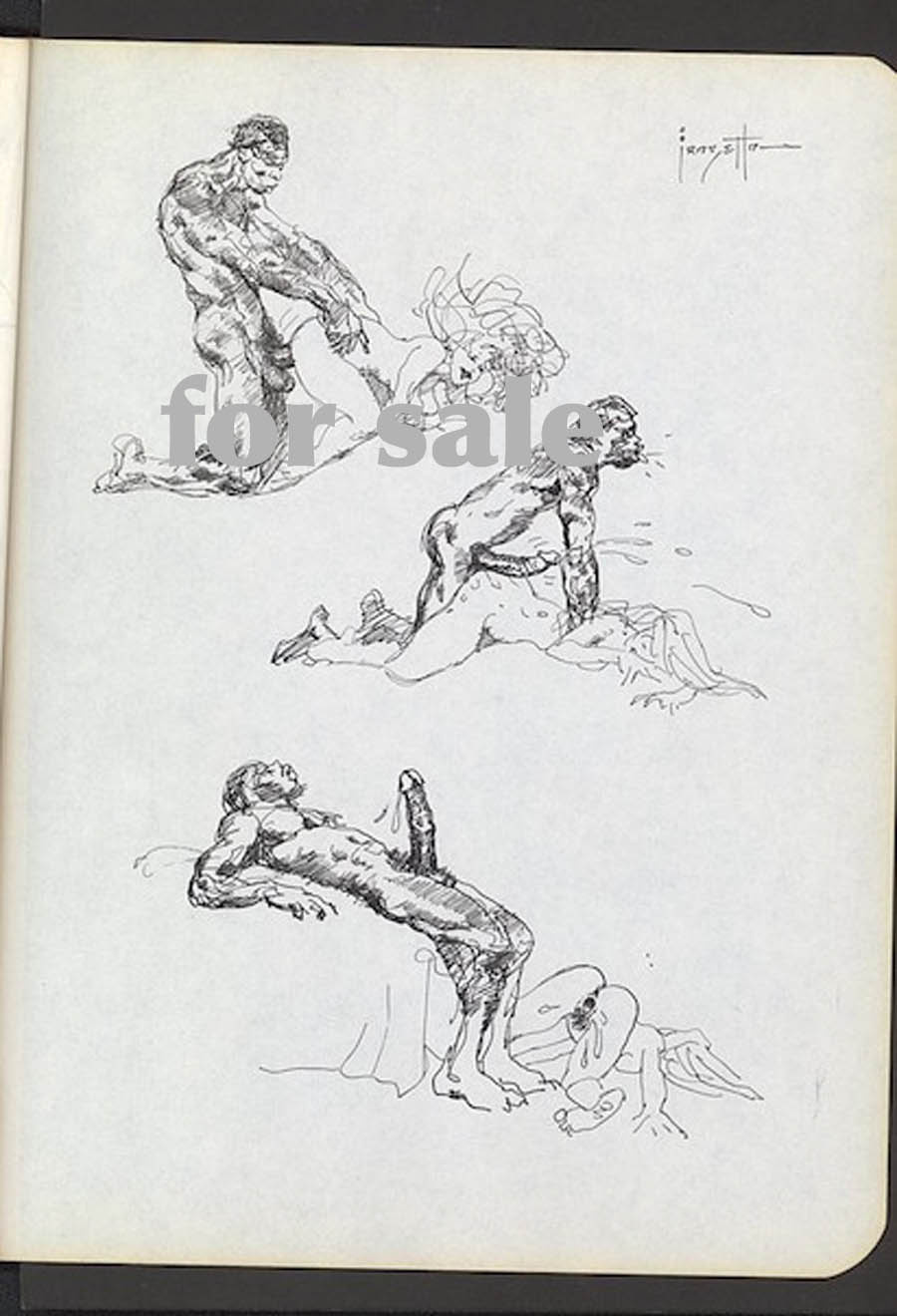

Everytime one of these things hits the stands, it’s as if Miller is pulling out his dick and saying, “Fuck you, DC! And fuck your pet rabbit!” The most obvious screw you was his infamous Superman with a package (he packs to the right) splash page/cover.

Miller fans point to moments like these as expressions of his genius and his innate feminist instincts—the drawing hand may be withering but that brain! It still works and wants to let the supermen (and their cocks) have it as good as the superwomen.

The people who go to conventions and collect original art were well apprised of this paradigm shift in Miller’s abilities at least a few months in advance of the general public, with responses ranging from delight at owning a hand drawn masterpiece from the Master to earnest attempts at retrieving whatever vestiges of dignity remained in the art—the equivalent of trying to pick a really dry piece of snot from your nostrils. Utterly disgusting for all concerned.

Any hesitation to declare this a sharp deterioration in artistic prowess does not simply reside in the level of respect Miller has garnered over the years from the fan community but the simple fact that you simply don’t make jokes about the afflicted. And Miller has looked pretty ill for some years (the exact nature of his ailment is a mystery). The internet gasped with incredulity when Miller took a photo with Stan Lee recently.

But there’s every indication that he’s on the mend. The recent photos while far from hearty are still a significant improvement over those from not so long ago. Like a mud-caked Batman in The Dark Knight Triumphant, Miller is having it out with the Mutant Leader. Something is telling him to stop with the art but he’s not listening to it; and that’s all for the best.

So if you’re sick (and there is by no means any public confirmation of this) and are still able to support yourself, I think more power to you. And if you want to do a Dark Knight IV all by your lonesome in years to come, well, I guess why not—DC deserves it, and fuck “artistic legacy.” But, you know, get Klaus Janson to help out a bit I think, now that you’ve both kissed and made up. Because there’s really no shame in getting help, especially when not getting help results in this:

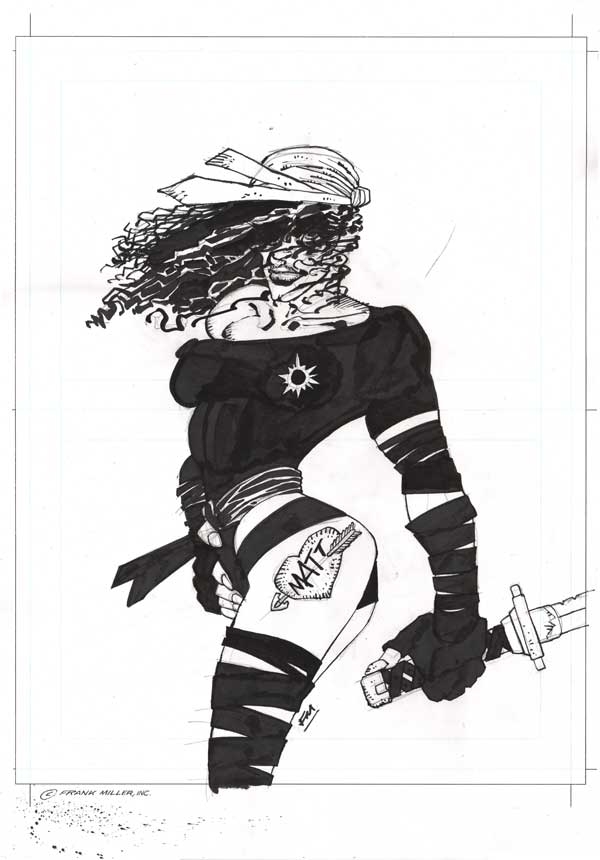

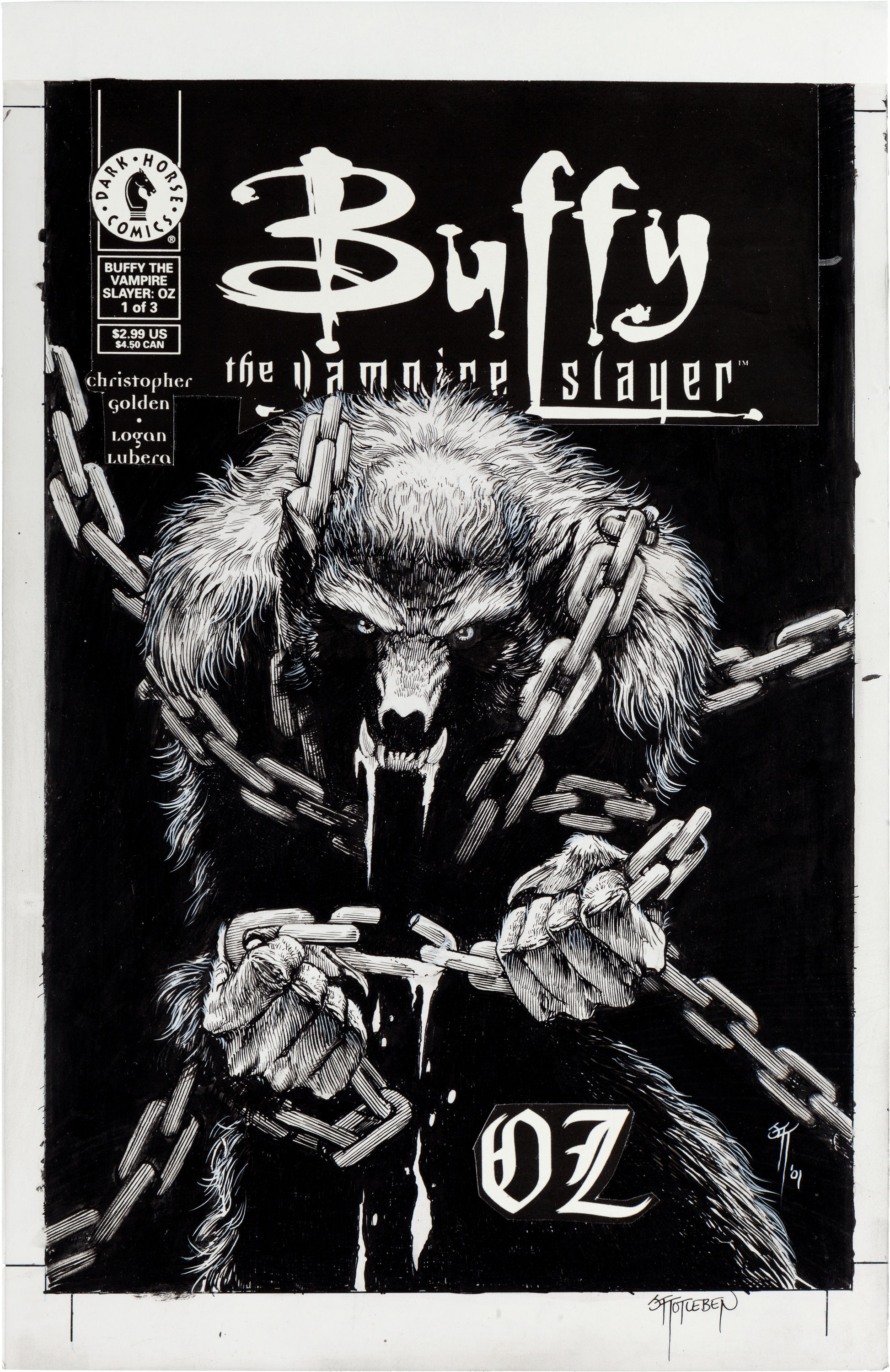

These monstrous ninja zombies are of course depictions of Miller most famous creation, Elektra; which sort of makes sense considering her resurrection in Miller’s early Daredevil comics. I guess if you created the character, you get to decide if the lady has flat-rectangular shaped nipples or has a tattoo of Matt Murdock on her left thigh or has glow in the dark areolae. There’s little doubt that Miller considers most of these images transcendent spank material.

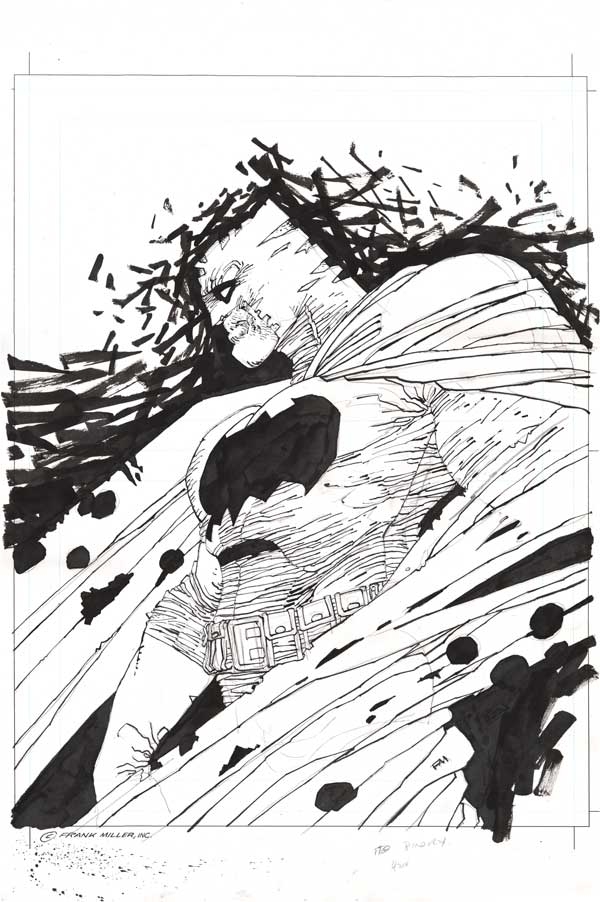

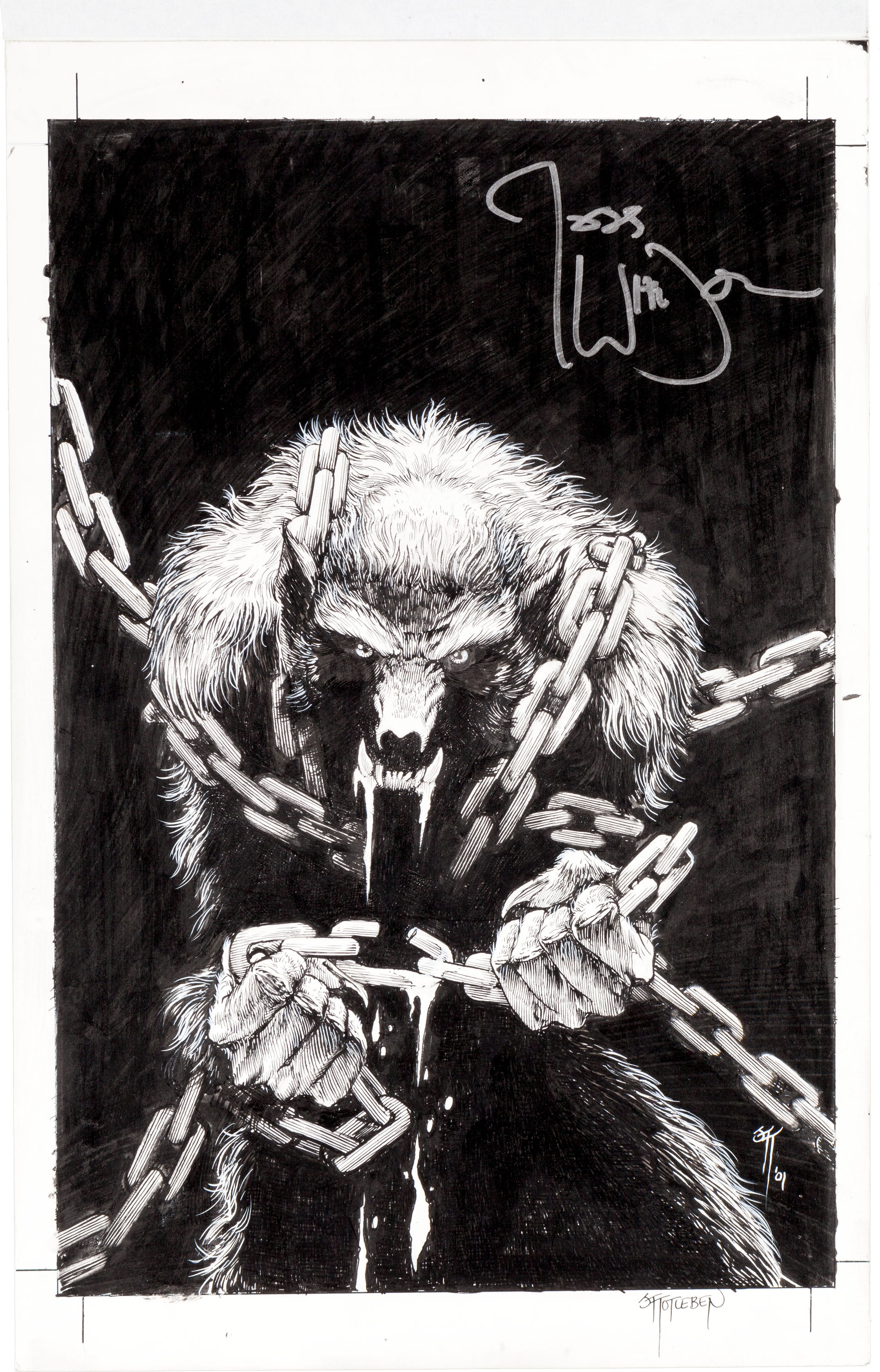

Speaking of which, how much do you think this wank material is worth? $2000 maybe? You need to account for the fact that we’ve had several suppositories of Quantitative Easing for close on 10 years (though with nary an effect on inflation). So maybe $4000-5000? Miller is a living legend in superhero circles afterall. Apparently a nice big Batman sketch like this goes for somewhere in the region of $10-12K.

The Elektras? 8.5-9.5K. There were nasty rumors circulating that customers who bought an Elektra stood a better chance of getting a Batman. When I heard about this from a fellow collector, I assumed it was a buy one and get one free deal. But no chance, Frank Miller (and his handlers) are nothing if not great businessmen.

Which only goes to show that you don’t need close readings or a smattering of comics history to understand the baseline ethic at work here. When exciting new conceptions of the decaying female form are greeted with ready wallets, then Capitalism dictates that we sell them. As for the rest, DC will just have to suck it up because they started it first.