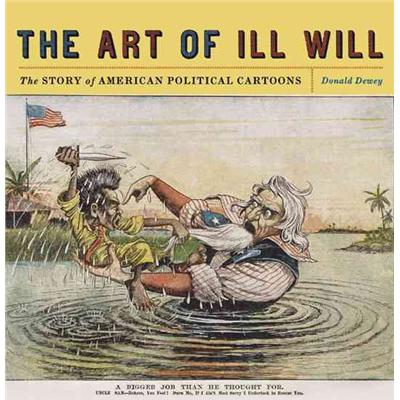

by Yasuhiro Nightow (Author), Oh! great (author), Satoshi Shiki (Author), Comikers (Author)

Currently available here for only seven dollars! It is otherwise sadly out of print in paper.

This is, hands down, my favorite art book. I have two copies, because I’ve worn out one.

If you’re curious about how a mangaka draws, inks, or tones, then this is the book for you. This is a compilation of various Comiker articles, tutorials, interviews, how-to-articles, and surveys. They include, among other things, a long list of responses of what various artists use to ink their manga (type of ink, type of nib, favorite pen, erasers, and so on). I love that kind of detail! It’s extremely useful to know, for instance, that some artists prefer quick drying ink because they draw more freehand and that others like slower drying but waterproof ink.

I solved some of my own difficulties by switching to a ink that worked better for the technique I was trying to use.

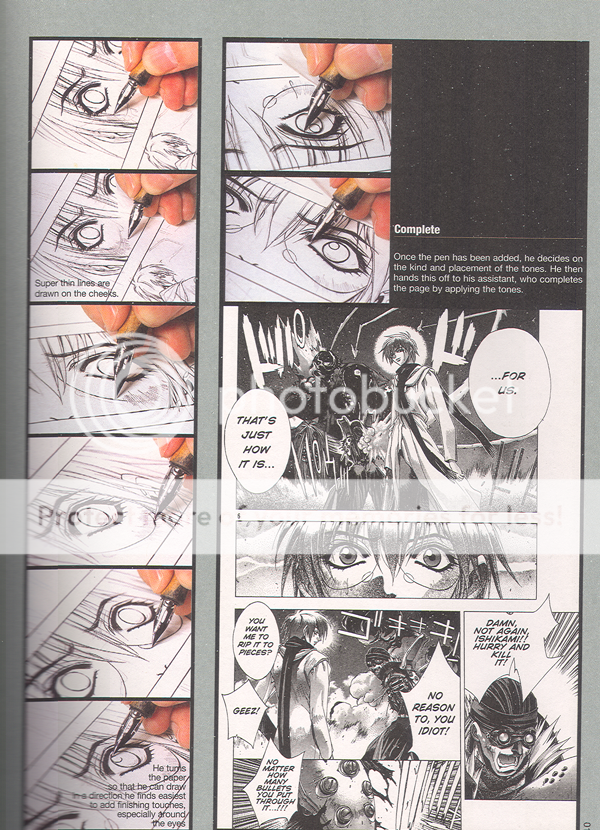

But besides being obsessively wonderful in detail, this book includes some pictures that are just damn cool. Want to see an artist go from basic layout pencil to perfected pencil to inked panels? They do this! And not just Joe Random Mangaka, they get great artists–Oh great, who does the back cover, is shown drawing and inking and toning the image. But it’s Satoshi Shiki’s work which makes my heart sing:

Check out the work on that eye! It’s fucking gorgeous. It just is. The line work! The thin-fat-thin! The eye lashes! The way the focus creates a widening eye effect! *happy sigh*

The previous page, which I didn’t scan but should have, shows him drawing the thing in pencils. *insert second happy sigh* Unfortunately, I cannot find any of his work translated into English and I’m not sure what magazine his current story is being run in. (Should some kind commenter know, I would be grateful for the info….)

Where was I? Oh yes. The purpose of the book and why the heck I’m talking about it.

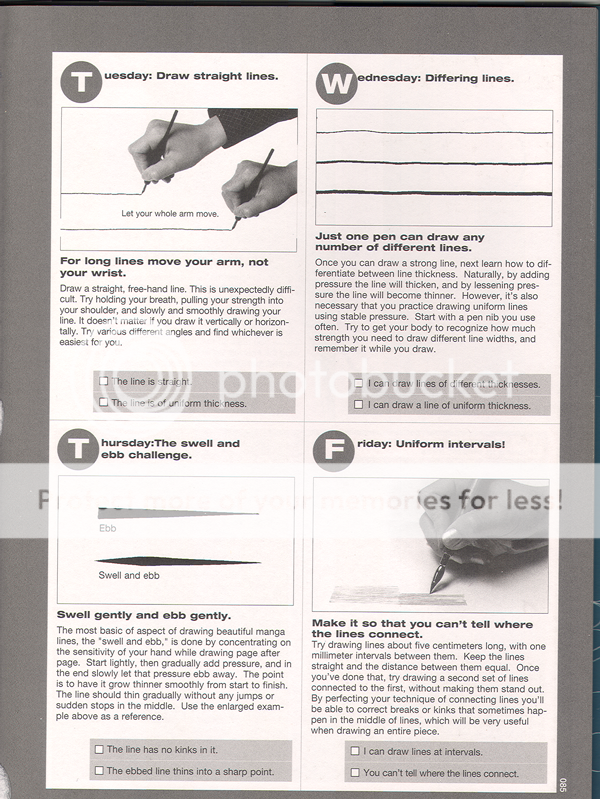

The book focuses on training the artist to use pen and ink skillfully, and furthermore, to use it the way that mangaka use it. A technical college wrote a wonderful tutorial designed to teach these techniques. This mini-school is worth the cover price of the book. It covers thin-fat-thin, using the pens to draw speed lines, creating effect line, varying character emphasis, inking for emotion, and much more.

One thing I love about the Japanese art books that I own is their emphasis on practice and their slow and careful steps. This book, like many other Japanese books, suggests copying the work of your favorite mangaka in order to learn. This is useful because it allows the hands to learn how to compose a page. It is also wonderful because it does not require the budding artist to work on all the techniques (underdawing, composition, placement, plot, character development, and on and on), but instead allows the artist to focus on mastering a single skill, inking. They mention, in their tutorial or the introduction, that they assign student the task of just making long, smooth lines freehand. Page after page of them until the student can do it easily and freely.

That may sound restraining and lacking creativity, but if what you want is to know that you can trust your hand to create the images in your heart, then it is a wonderful way to learn.

So here is an example of the tutorial so you can judge for yourself:

In any case, I feel strongly that this book is AWESOME. Which leads me into the second portion of my topic.

As you might guess, I’m a bit of an ink whore. I love ink. Adore it. Hug it. Collect it.

‘Uh, collect it?’ you may ask warily. Yes! Collect it. You see, in my copious spare time (when I’m not working overtime or going to grad school full time), I like to ink comics. I find it relaxing. I don’t, you know, post it anywhere. I ink and then when I’m done, I set the inked pages in a big box and when the box gets full, I recycle it. Sometimes I send it to friends. But mostly I don’t. Like I said, I just do it to relax. But like any good obsessive little comic addict, I have my preferences and my weird habits. So I have a lot of ink. I have, at last count, something like a dozen kinds of ink. Deleter 1-6 of course, and some Sumi ink, and some Higgins Ink, and my hoarded and beloved Pilot Drawing Ink (only available in Japan), and IC Comic ink, and um, some others that I forget. Windsor Newton and stuff? I don’t know. Not to mention the white ink.

So I’m going to review the inks. My thought was to draw a few panels in each ink, scan at least one page worth, and also draw some strictly technical panels (effect lines, for instance). I’m not sure if any artists read this or would find it useful, but I live in hope. I plan to include the following in each example page:

- A character close up and one mid-sized

- Something emotive

- Place, building, interior

- Effect lines or background hatching

- Fine detail (flowers, fine shading)

- Flowing lines (hair or clothing)

After I’ve reviewed several inks, I thought I’d have some cage matches. You know, put two inks together and draw the same thing with them and let you all vote as to which was better at hatching or speedlines.

What do you all think? Are there any aspects that would be most helpful? I plan to include in each review the strengths and weaknesses of the inks (to me), their waterproofness, their smear level, and how they work (ease of control, etc).