The entire Tintin in Otherland series is here.

____________________

The immediate aftermath of the war was harsh for Hergé, even though he could be accused, at worst, of passivity.

He learned his lesson – what political satire there was in his books would henceforth be muted; minorities treated with greater respect. The books would be revised and whitewashed.

Of course, there was little that could be done to arrange Tintin au Congo. The Black’s pidgin was made somewhat more grammatical. And, tellingly, the album was “de-Belgified”. References to Belgium and Tintin’s own ‘Belgianness’ were excised.

This can partly be due to the great winds of de-colonisation that were stirring in the postwar world that Hergé sensed; more likely, with Tintin becoming more and more an international success, Hergé was loath to keep his hero tied down to one nationality. (Tintin au Congo was renamed Tim-tim em Angola by his Portuguese publisher – Angola being, of course, Portugal’s colony – and Tintin dans la Brousse — Tintin in the Bush – by one French publisher.)

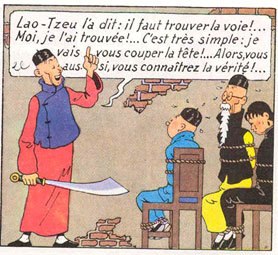

Note the difference between the 1931 (top) and 1946 (bottom) versions.

Originally, Tintin was dispensing a geography lesson: “My dear friends, I shall speak to you today about your homeland: Belgium!” In 1946, he’s giving a maths lesson.

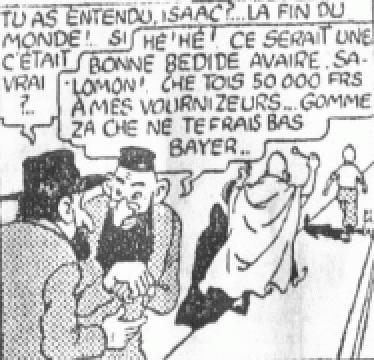

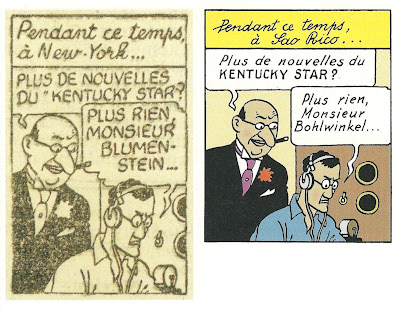

We’ve already seen how Hergé whitened the Blacks in his pre-war albums. He was to go further and de-Judaise his Jews. Blumenstein became Bohlwinkel in L’Ile Mystérieuse. And he went even further with Tintin au pays de l’or noir.

This adventure takes place in the Middle East, starting in Palestine. The album was first begun in 1939, when Palestine was under British mandate, then set aside when Belgium was invaded—obviously a bad time to show sympathetic British cops. The story was reworked and published in 1950.

The Stern group and the Irgun were escalating an often violent campaign to drive the British out and establish a Jewish state. In the album, a sub-plot has Tintin mixing it up with the British police and members of the Irgun due to a case of mistaken identity.

The Jews in this book are treated neutrally, even sympathetically.

Captured Irgun militants

However, at the request of his British publisher, Methuen, Hergé excised Palestine and Jews from the book : Palestine becomes the fictional Khemed, Haifa is now Khemkhâh, and the British police are Arabs; the fight for Israel becomes a mere power struggle between different factions. It is noteworthy that Hergé made these changes as late as 1971, showing an ongoing hypersensitivity to any possible accusation of racism, even when unjustified.

He was especially leery of charges that his master villain, Roberto Rastapopoulos, was an anti-Semitic caricature:

« Rastapopoulos, for me,” wrote Hergé, “is more or less Greek, a shady Levantine character, without a country, that is without faith or ethical code. Another detail, he is not Jewish!”

The oily “Levantine” is, of course, another nasty stereotype; and the contempt shown for the cosmopolitan is another reactionary mainstay.

Already, during the war years, Hergé had switched to innocuous escapism for his books. Le secret de la ‘Licorne’/Le Trésor de Rackham le Rouge are grand treasure-hunts in the South Seas. The last of the wartime books was also meant to be an escape from the troubled times, involving neutral South America : Les sept Boules de Cristal, a two-part adventure paired with its sequel Le Temple du Soleil.

This is one of the more interesting books from our standpoint. It shows Hergé slowly being weaned from the xenophobia and racism that marred so much of his earlier work; but the process is far from completed.

Basically, it’s a variation on the “curse of Tutankhamen” chestnut, with Peru and Incas taking the place of Egypt and Pharaohs. The scientists who have brought the mummy of the Inca Rascar Capac to Europe are being struck down by a mysterious illness. They are in fact being targeted for punishment for blasphemy by descendants of the Incas living in a secret Andean enclave. When Professor Tournesol is kidnapped, Tintin and Haddock follow his captors to South America, where they are taken prisoner and sentenced to die. Tintin saves the day by the old “eclipse” ruse, terrifying the natives by seeming to blot out the sun. Our friends are released with a warning.

The first thing that strikes one is that the villains here aren’t really villains. They have an authentic grievance against the White man, who comes and despoils their heritage. As one character remarks to Tintin , how would we feel if Egyptian or Peruvian archaeologists came to Europe and opened the tombs of our kings to rob them? Hergé was beginning to empathise with the so-called savage; quite an improvement on the album L’oreille cassée, wherein Amazonian Indians are portrayed as weird and barbarous.

In Peru, Tintin picks up another sidekick of the Chang type, an Indian child named Zorrino. Tintin rescues him from a beating by two White bullies:

Zorrino is brave, loyal and dignified.

Overall, then, we can see that the Indians—the Other – are treated with a measure of respect.

And yet, they remain the Other, an insidious source of dread. The avenging Incas are lured to Europe by the stolen mummy: it’s as much a contamination as a curse. Keep away from the Other, and keep the Other away from us.

Tintin’s ruse would never have worked: the Quechua Incas were superb astronomers. It is insulting to suppose them stupid enough to fall for it.

Finally, the trappings of exoticism remain, alluring, alienating:

Hergé himself was changing. His former reactionary colleagues were no longer there to influence him ; his assistants included such cosmopolitan men as artists E.P.Jacobs or Jacques Martin (who assured Hergé of the reality of the death camps, which he’d seen.)

The grip of Catholicism on his was relaxing; in time, he would become an agnostic, fascinated by Buddhism and especially Taoism. He collected modern and contemporary art: Calder, Rauschenberg, Lichtenstein, Frank Stella.

Herge with Andy Warhol, who cited him as an influence

He travelled extensively—finally discovering the foreign parts he’d drawn for decades. Hergé was evolving.

Not that he didn’t slip up. In Coke en Stock (The Red Sea sharks), the Black victims of the slavers are shown to be dignified in their Muslim faith, but fairly stupid as well.

Up till this point, one might suppose that Hergé’s turn away from racism and xenophobia was dictated as much by political fears and commercial considerations. His next album—considered by many (including me) to be his finest work—would prove that his personal evolution was sincere. And, fittingly, it would feature again Chang, the young Chinese who first opened Hergé’s eyes to other cultures.

In Tintin au Tibet, again, there is no villain: the adversary is nature itself, in the forbidding snows of the Himalayas. The Tibetans are depicted with admiration and respect, whether sherpa guides:

or lamas :

or kids:

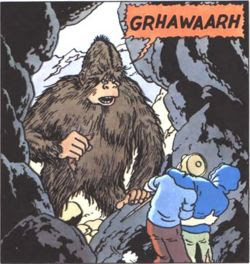

But the ultimate image of the Other is that of the Monster, such as the Yeti, or Abominable Snowman :

Yet we come to learn that the Yeti is a being of kindness, even love.

Hergé took the side of the Other in Les Bijoux de la Castafiore, wherein a group of Roma (“Gypsies”) are unjustly accused of theft. Haddock protects them and gives them shelter, though Hergé wisely shows them to be skeptical.

And in Hergé’s last album, Tintin et les Picaros, we can feel his indignation at the treatment meted out to the Amazon natives, deliberately kept enslaved by the White man with lashings of free alcohol .

So, yes, the man matured and evolved beyond his prejudices.

Can I say the same for myself?

Next instalment: the Tintin reader on trial.

All Tintin art copyright Moulinsart

_______________________

The entire Tintin in Otherland series is here.