Langlois’ formulation is the denial of time: an idea of history not as something past, things having happened and remembered, but something entirely now, aggregated all together, present – meaning both presence and in the present tense. — Caroline Small

There was once a man; he had learned as a child that beautiful tale of how God tried Abraham, how he withstood the test, kept his faith and for the second time received a son against every expectation. When he became older he read the same story with even greater admiration, for life had divdied what had been united in the child’s pious simplicity. The older he became the more often his thoughts turned to that tale, his enthusiasm became stronger and stronger, and yet less and less could he understand it. Finally it put everything else out of his mind; his soul had but one wish, actually to see Abraham, and one longing, to have been witness to those events. — Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling

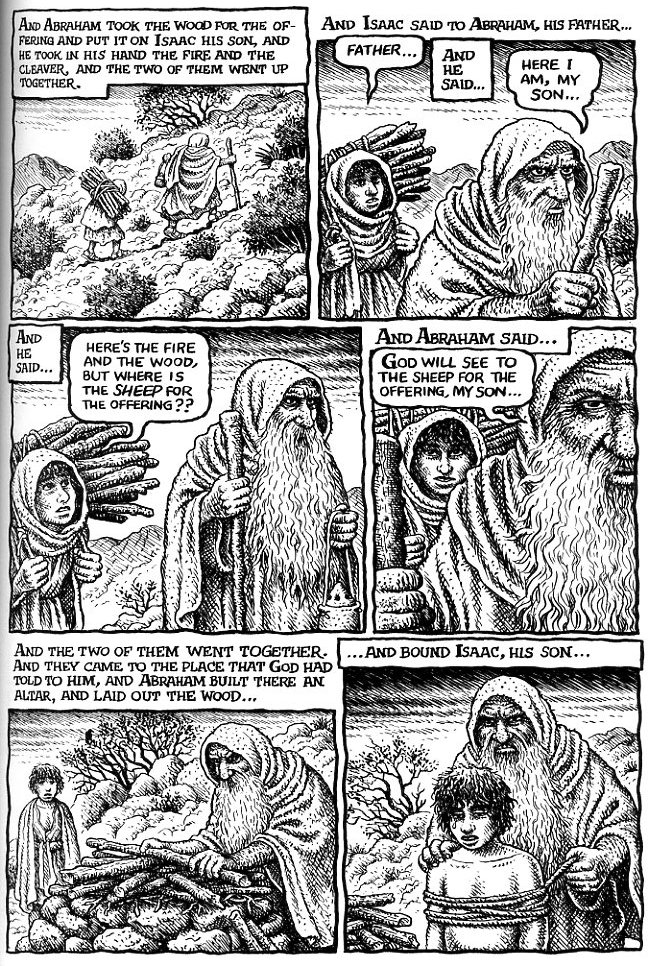

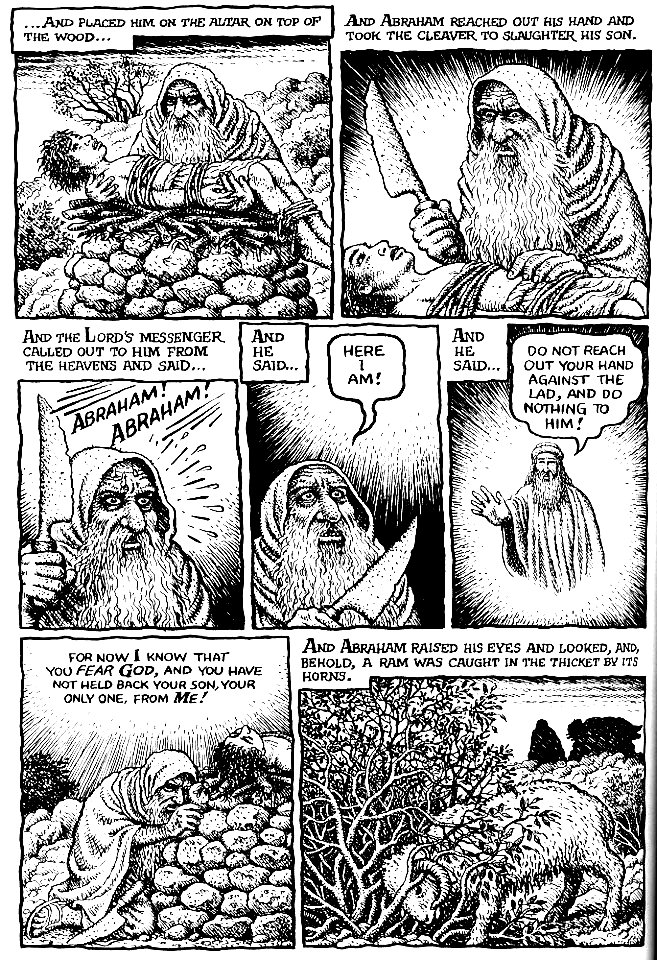

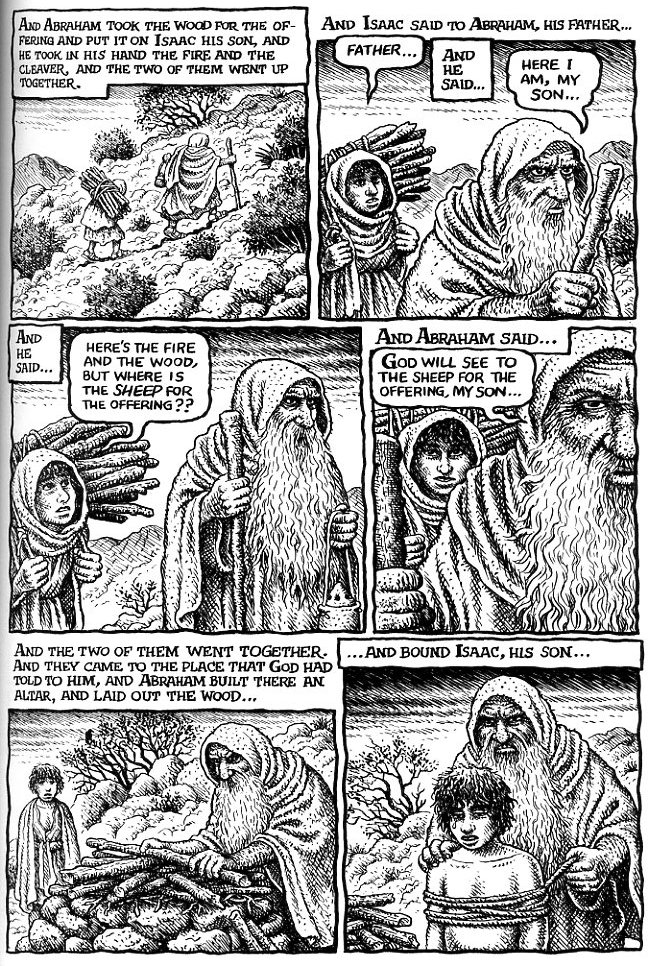

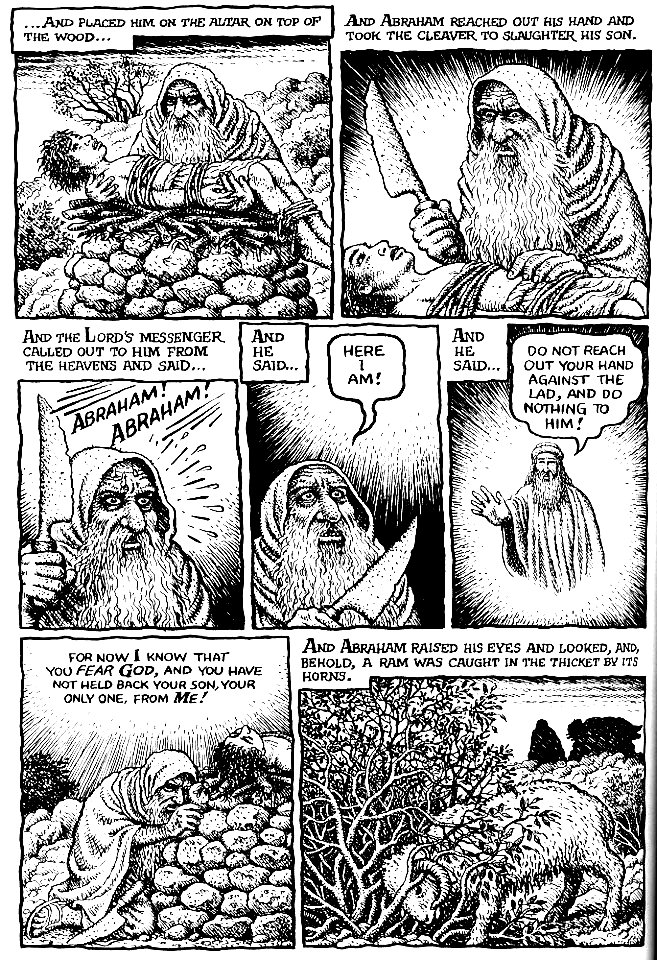

R. Crumb’s illustrated Book of Genesis does precisely what Caroline Small and Kierkegaard ask of art and of faith. In Crumb’s literal reading, with its physicality, and its playful touches of cartoonishness, the Bible is transformed from a fusty, inaccessible monument to boredom and bewildering begats into “something new,” a text that makes the familiar alien, or, at least, more familiar. In giving flesh to the Biblical narrative, Crumb allows us to do what Kierkegaard, tragically lacking the technology of sequential pictograms, could not. We can “actually…see Abraham” drawn before us, and watch the flickers of agony, hope, love, and relief flow across his comfortingly craggy patriarchal visage, as if he were Patrick Stewart reacting with satisfying aplomb to the Romulan menace.

Moreover, Crumb penetrates to a truth that Caro and Kierkegaard fail, each in their own way, to understand. Making something new is best done, not through imaginative engagement, but through rote drudgery. Clichés are our deepest selves; to present them with minimal comment or inquiry is therefore the artist’s highest calling.

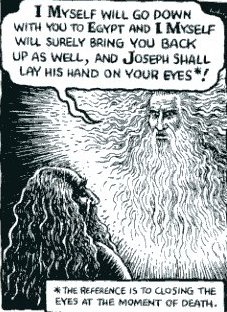

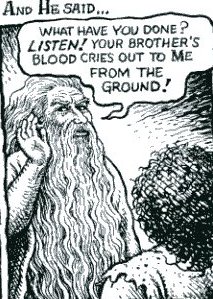

Pesky floating bearded heads — didn’t I spray for those?

You can tell I am remembering because I am pointing to my head!

You can tell I am listening because I am cupping my ear!

Why do we see God as a bearded patriarch? Crumb cunningly investigates and undermines this image through his steadfast refusal to investigate or undermine it. Deftly deploying the poverty of his visual imagination as well as a deep spiritual engagement, Crumb shows us a God daring in His vacuousness; a children’s book deity who pantomimes and points in case the kiddies can’t parse the text, yet who thoughtfully problematizes His own superficiality not through any actual ideas or initiative, but rather through the very fact of being in a big honking coffee table book by R. Crumb.

Crumb’s insistence on transcribing every word of Genesis without bowdlerization or omission again makes history new by bringing into focus many aspects of the narrative previously glossed over by Christian and secular readers alike. For example, Crumb shows us that women in the past had nipples. He also demonstrates that Adam had a penis, even if nobody else in particular did, (Update: Robert in comments points out that at least one other person in the book has a penis too.) and that when people are anxious, little sweat drops fly off of them.

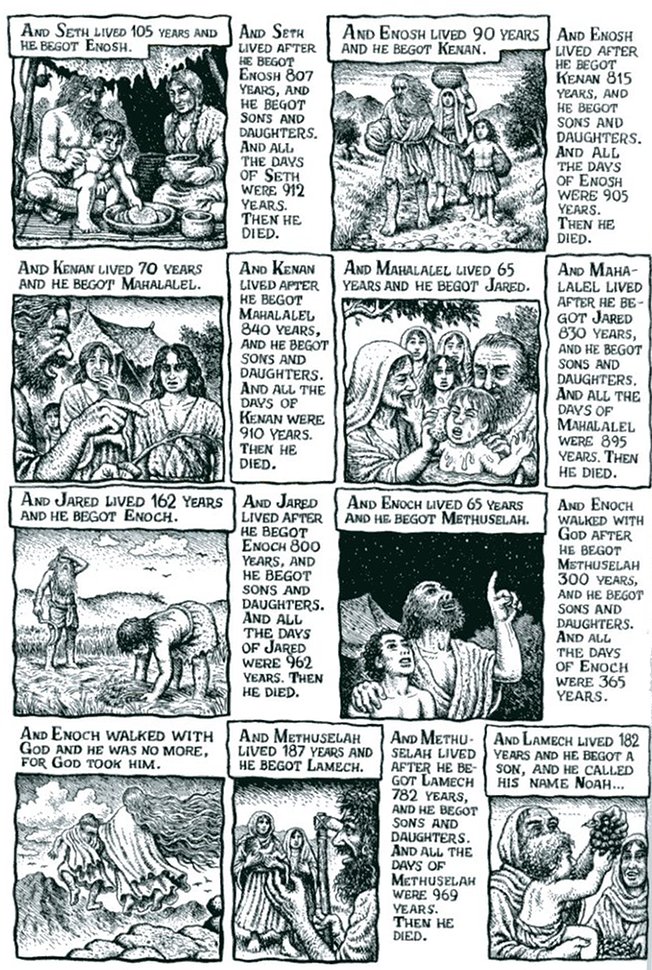

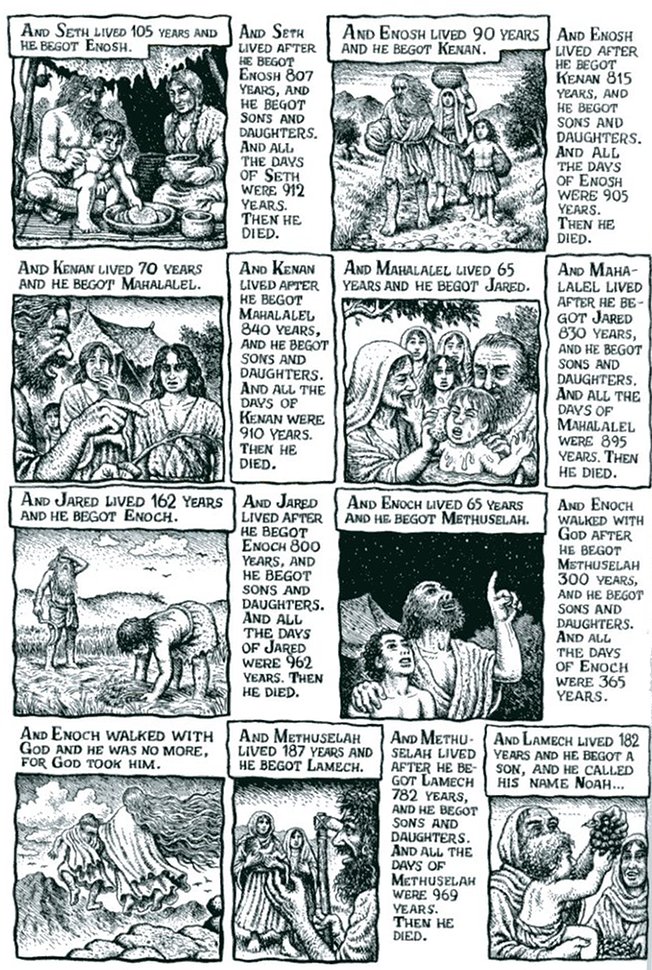

And, of course, he provides visual referents for the begats.

Another artist, less versed in the transcendentally validating power of banality, might have attempted to visually integrate the passage’s obsessions with patriarchy, seed, age, and death. One can imagine Chris Ware, for example, creating a single intricate image of lineage, or Johnny Ryan (channelling the younger Crumb) treating the text as an opportunity to create an extended daisy chain of sentient semen. Far better Crumb’s vision — a series of small disconnected drawings of more or less random scenes of life, recalling a light television montage that gets up on its hind legs to say, “Humanity! How heartwarming!” Time passes, life passes, Crumb draws, and the strings swell. Crumb has commented in interviews on the strangeness of the Biblical narrative; what better way to emphasize that strangeness than to turn it into a drab sentimental parable?

Ng Suat Tong started this Genesis discussion off by comparing Crumb’s visuals to the efforts of great artists of the past. Of course, it is not really cricket to put Crumb next to artists like Blake since Crumb draws lots of pictures on a page, thus obviously quantitatively overwhelming painters who only drew one at a time. Similarly, it seems unfair to place Crumb beside mere authors since mathematically: pictures + words> words. Still, I think it’s worth looking at this passage by Kierkegaard to show exactly what Biblical exegesis has been missing up to this moment.

It was early morning. Abraham rose in good time, had the asses saddled and left his tent, taking Isaac with him, but Sarah watched them from the window as they went down the valley until she could see them no more. They rode in silence for three days; on the morning of the fourth Abraham still said not a word, but raised his eyes and saw afar the mountain in Moriah. He left the lads behind and went on alone up the mountain with Isaac beside him. But Abraham said to himself” “I won’t conceal from Isaac where this way is leading him.” He stood still, laid his hand on Isaac’s head to give him his blessing, and Isaac bent down to receive it. And Abraham’s expression was fatherly, his gaze gentle, his speech encouraging. But Isaac could not understand him, his soul could not be uplifted; he clung to Abraham’s knees, pleaded at his feet, begged for his young life, for his fair promise; he called to mind the joy in Abraham’s house, reminded him of the sorrow and loneliness. Then Abraham lifted the boy up and walked with him, taking him by the hand, and his words were full of comfort and exhortation. But Isaac could not understand him. Then he turned away from Isaac for a moment, but when Isaac saw his face for a second time it was changed, his gaze was wild, his mien one of horror. He caught Isaac by the chest, threw him to the ground and said: “Foolish boy,, do you believe I am your father? I am an idolater. Do you believe this is God’s command? No, it is my own desire.” Then Isaac trembled and in his anguish cried” “God in heaven have mercy on me, God of Abraham have mercy on me; if I have no father on earth, then be Thou my father!” But below his breath Abraham said to himself: “Lord in heaven I thank Thee; it is after all better that he believe I am a monster than that he lose faith in Thee.”

Kierkegaard uses the story as the occasion for an inquiry into faith and love between God and man, father and son. He does this by treating the story as his own; it is a coat that he can put on, adjust, take in or let out. For him, reverence involves dispensing with reverence; to understand the story of Abraham as it is, he has to defile it with his own imagination.

Crumb, on the other hand, treats the story as an inquiry into the story. It is his job to clothe the text, not to have the text clothe him. You can see him doing his best to provide a striking garment; Abraham looks grimly determined here, sweatily panicked there, movingly relieved in the center panel of the second page (perhaps the strongest single image in the book, despite the yep-there-it-is-again light from heaven.) But this is gilding, not defilement. Kierkegaard fucks with Genesis and ends up begatting a new creation; Crumb puts a few ribbons of varying construction in the text’s hair and sends it on its way.

And, surely, this is the great contribution of comics to Biblical criticism and to art. Without much of a tradition of accomplishment, sequential pictographs are perfectly situated for the aesthetic task of the future — namely to rehash what has gone before as doggedly and unimaginatively as possible. Perhaps Caro was wrong after all; the best way to deny time is not to recast the past as present, but the present as past. Nothing has happened, no one has spoken, neither God nor our ancestors have taught us anything, and so the most lackluster retread deserves the most heartfelt hosannahs. If defilement is reverence, then reverence is the truest defilement —both of the Bible and of art, which are cast together, through the power of Crumb’s genius, out of the flawed garden of giving a shit and into the absolute purity of irrelevance.

_____________________

For a less gratuitously mean-spirited take on R. Crumb’s Genesis, I’d urge folks to read the heartfelt and thoughtful defenses by Alan Choate andKen Parille. The entire ongoing back and forth about Genesis on this blog can be found here.

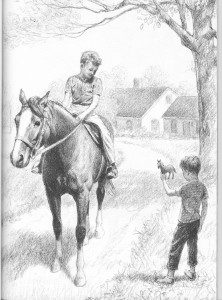

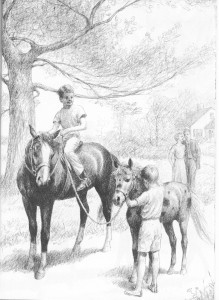

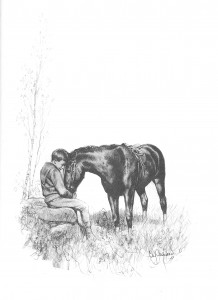

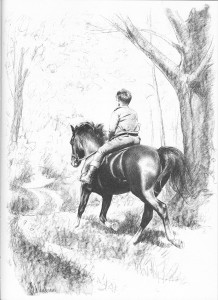

The drawings in this story are especially well-done with the pony rich in shiny coat and detail, and the forest and background rougher and more gestural as they enter the forest for their adventure:

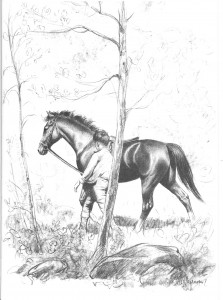

The drawings in this story are especially well-done with the pony rich in shiny coat and detail, and the forest and background rougher and more gestural as they enter the forest for their adventure: In the tradition of plucky ponies everywhere, Blaze refuses to go the wrong way and eventually leads Billy out of the forest:

In the tradition of plucky ponies everywhere, Blaze refuses to go the wrong way and eventually leads Billy out of the forest: They escape the forest and the building storm, just in time. Simple stories, simple drawings, but lovely.

They escape the forest and the building storm, just in time. Simple stories, simple drawings, but lovely.