On HU

We started the week off with Eric Berlatsky’s guest post on space, time, comics, and modernity.

Caroline Small reviewed an exhibit of Vorticist art.

I reviewed Reinhard Kleist’s graphic autobiography of Johnny Cash.

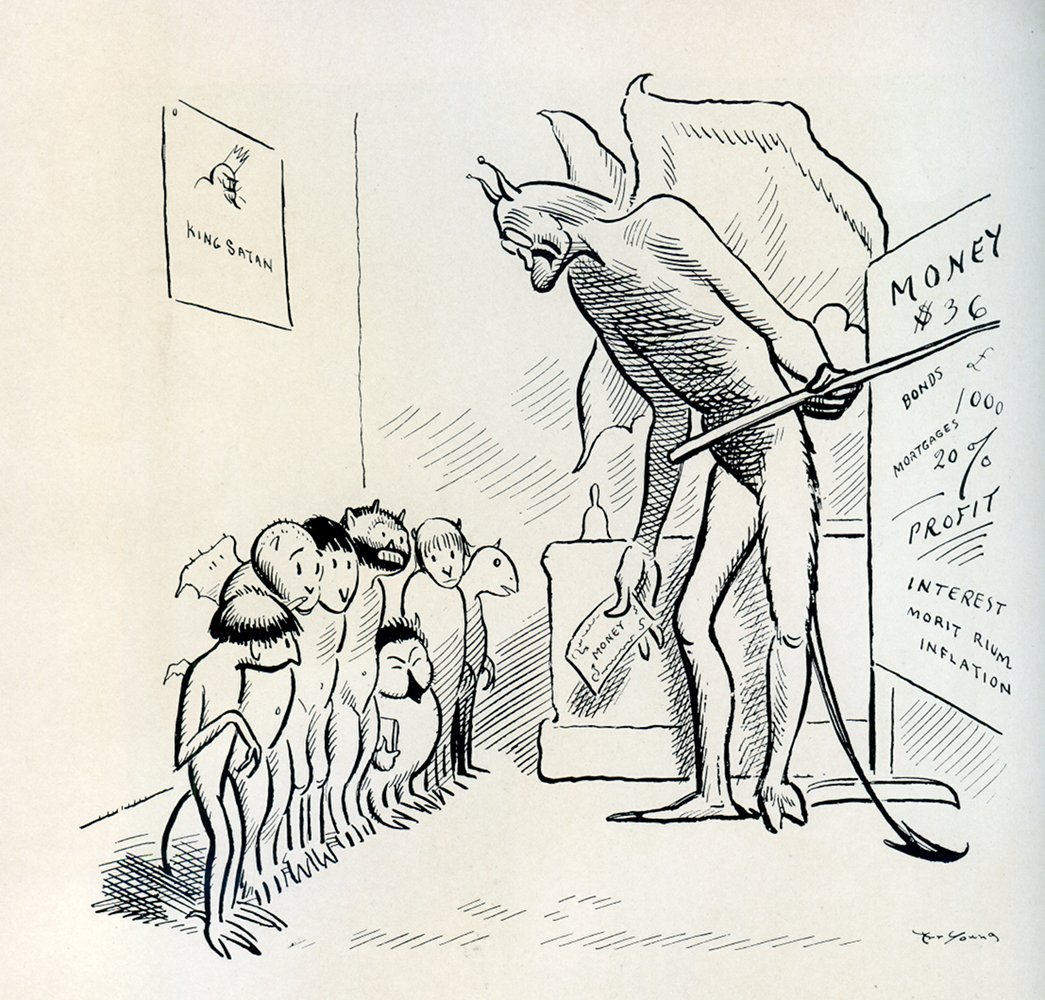

I discussed Christianity, humor, and cartoonist Art Young.

Artist and editor Ryan Standfest replied to my essay about Art Young.

Vom Marlowe discussed art resources for drawing the human figure.

Richard Cook provided a gallery of Santa’s appearances on comics covers.

I provided an electronica mix for download.

And Alex Buchet continued his series on language and comics with word and phrases from Al Capp, Walt Kelly, and more.

Utilitarians Everywhere

At Splice Today I explain why lefties against the compromise tax bill are idiots.

I’m a liberal pinko commie. I get up on the left side of the bed, and while I brush my teeth I blame America first. The only person I think should be waterboarded is Marc Thiessen. When I hear stories of rabid Brits trashing the royal limo to protest tuition hikes, I wonder why our cajone-less electorate can’t summon the courage and basic decency to kneecap some hedge fund managers. I’m in favor of abortion rights, single-payer healthcare, and unremitting class warfare. The rich got where they are mostly by luck and subterfuge, and at least 50 percent of what they’ve got should be taken from them and put into saving Social Security or fixing Medicaid or, hell, just taken from them on general principles because income inequality corrupts the political process and also because fuck them.

Also at Splice Today, I talk about Chuck Berry’s 1987 autobiography.

It’s maybe fitting, then, that Berry’s last great artistic effort wasn’t a hit but a personal testament. His 1987 autobiography was, according to the man himself, “raw in form, rare in feat, but real in fact. No ghost but no guilt or gimmicks, just me,” and you can hear the truth in the rock of the phrase and the roll of the alliteration. Berry says he’s only read six hardbacks in his life, and that the dozens of paperbacks he’s paged through were “only for the stimulation.”

Other Links

This isn’t something I find myself thinking very often, but I agree with Megan McCardle.

Tim Hodler does the AV Club a huge favor and is mostly pilloried for it. (You need to scroll through comics to see the full extent of the fracas.)