Nasher Art Museum at Duke University

Durham, NC

Through January 11

Peggy Guggenheim Collection

Venice, Italy

25 January – 15 May 2011

Tate Britain

London, UK

Tuesday 14 June – Sunday 4 September 2011

“What is Vorticism? Well, like Futurism, and Imagisme, and Cubism, essentially it is nonsense. But it is more important than these other fantastic, artistic, and literary movements because it is their sure conclusion. It is important not because it is the latest, but because it is the last phase of the ridiculous rebellion which has given the world the “Portrait of a Nude Descending the Stairs” and the writings of Gertrude Stein. It is the reduction ad absurdum of mad modernity.”

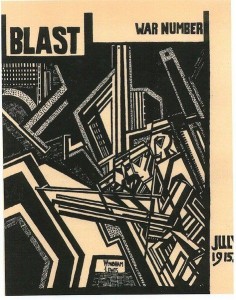

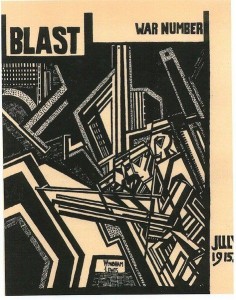

When The New York Times published this dismissal of “modernity” in August of 1914, only a couple of months had passed since the Vorticists had published their manifesto in the first volume of their magazine Blast. Earlier that year, Dora Marsden had established her journal The Egoist, Vorticist leader Wyndham Lewis had broken with the Bloomsbury artists and established the Rebel Art Center, and the Vorticist poet laureate Ezra Pound had published his anthology “Des Imagistes.” “Mad Modernity” was in full swing (despite that little matter of an assassination).

On the same day that the Times “blasted” Vorticism, they also published a glowing review of a show of American art in Paris featuring work by the figurative painters Ernest Lawson, Bryson Burroughs, and Harry Lachman, as well as the sculptor Cecil Howard. From the vantage point of New York, then conservative and academic, all the European modernisms were madness — the same madness.

Throughout 1914, however, Pound and Lewis were at great pains to emphasize that Vorticism was not the same. In June, they publicly rejected Marinetti’s attempts to co-opt them as a sub-movement of Italian Futurism, despite having previously taken advantage of his high profile for a fundraiser for the Rebel Art Center. Blast 1 is littered with aggressive criticism and rejections of all the modernisms, in an effort to publicly situate Vorticism as a uniquely advanced synthesis. In the introduction to the excellent exhibition catalog for the exhibit reviewed here, Philip Rylands describes it as the “most advanced, the most sharply characterized of the London-based avant-gardes,” including the Bloomsbury movement that fostered Virginia Woolf.

This is even clear from the first time the term “Vorticist” appeared, in a 1914 advertisement for the upcoming Blast 1, printed in the literary magazine The Spectator:

The Manifesto of the Vorticists. The English Parallel Movement to Cubism and Expressionism. Imagism in poetry. Death blow to Impressionism and Futurism, and all the refuse of naïf science.

The Exhibit

The exhibit of Vorticist art currently on display at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, curated by the Nasher in cooperation with the Guggenheim in New York, is the first exhibition of Vorticist art in the United States since Pound mounted his own exhibition at the Penguin Club in New York in 1917. For that reason alone, it is worth attending.

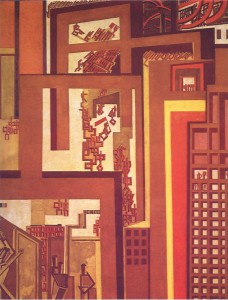

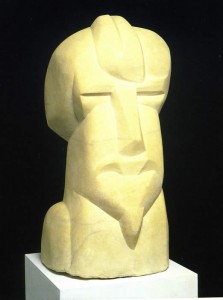

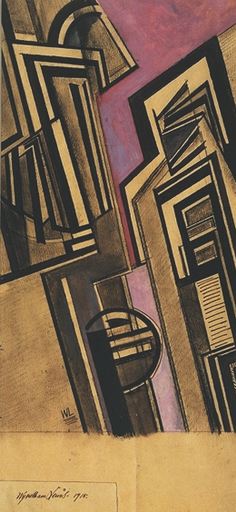

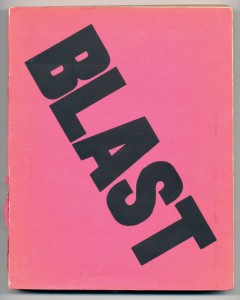

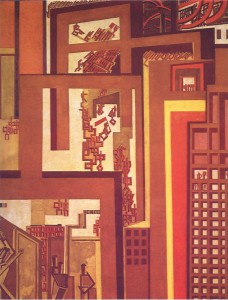

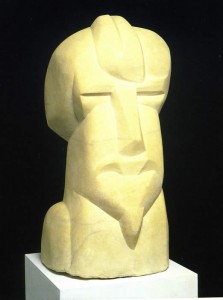

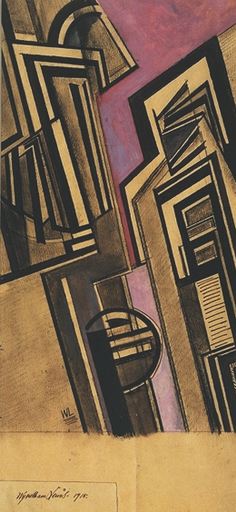

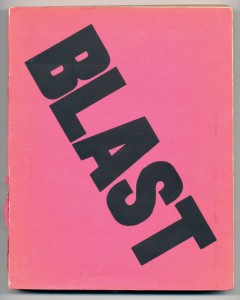

The exhibit is organized in five parts: A display of major works, including Gaudier-Brezska’s Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound (below), Wyndham Lewis’ The Crowd (right), and Jacob Epstein’s Torso in Metal from Rock Drill (below, third), begins the exhibit. That is followed by “re-creations” of the three exhibitions, including Pound’s at the Penguin, held between 1913 and 1917 when Vorticism was a current avant-garde, and a section devoted to the movement’s magazine Blast.

“Re-creation” is a strong word, as many of the originally exhibited artworks are lost – but the curators attempted to gather as many works from the original exhibitions as possible. Of particular note are the paintings by Helen Saunders, which were believed lost but turned up in boxes at Roosevelt University in Chicago, and the vortographs of photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn.

The impact of seeing all these works collected together – as opposed to the usual one-off buried in a room of “minor modernisms” – is significant. In this context, the aesthetic consistency among the movement’s practitioners, their debts to Jacob Epstein and to both Cubism and Futurist painting, and the inspiration they found in the urban landscapes of Northern English cities and English industrialism, all become readily visible.

The section focusing on Blast doesn’t make nearly the same impact. That section and the opening display of “major works” are both haunted by the spectres of literature and philosophy – particularly Pound, who coined the term Vorticism, and Wyndham Lewis, who was as much a novelist and essayist as a painter. Their mutual “friend” T.E. Hulme – in scare quotes because that friendship was characterized by competition and melodrama, which led to Hulme’s exclusion from Blast 1 – was almost singlehandledly responsible for Vorticism’s philosophical orientation, culled from his translation of Bergson and his friendship with the Expressionist philosopher Wilhelm Worringer. Add in Pound’s influential friendships with the feminist anarcho-individualist Marsden and the writer T.S. Eliot (who was also published in Blast), and it’s indisputable that Vorticism was as much a literary, philosophical, political, and social movement as it was a visual aesthetic one. (There was even Vorticist music, eventually.)

The Nasher exhibit emphasizes Blast as a material object, however, displaying original copies of both volumes in long cases, with framed original drawings for the magazine hanging above the cases. Although the physicality of this presentation gives a geeky thrill, Blast was never intended to be enclosed within a display case (to the exhibitors credit, a new facsimile edition of Blast 1 was developed just prior to the exhibit and is available in the gift shop or here).

There is no Vulgarity in Revolt

The manifestos of “mad modernism” depended on mechanical reproduction and fed off the vibrancy of their artistic activism. The avant-garde was here set against both aestheticism and academicism, as Lewis’ stated directly in Blast:

To make the rich of the community shed their education skin, to destroy politeness, standardization and academic, that is civilized, vision, is the task we have set ourselves.

To believe that it is necessary for or conducive to art to “improve” life, for instance, make architecture, dress, ornament, in “better taste,” is absurd.

The Latins are at present, for instance, in their ‘discovery’ of sport, their Futuristic gush over machines, aeroplanes, etc., the most romantic and sentimental ‘moderns’ to be found. It is only the second-rate people in France or Italy who are thorough revolutionaries. In England, on the other hand, there is no vulgarity in revolt. Or rather, there is no revolt, it is the normal state. … the nearest thing in England to a great traditional French artist is a great revolutionary English one.

The spirit in these quotes from the preface and manifesto, not to mention its influence on the experience of the visual art works and literature reproduced in the subsequent pages, is lost when the book is put in a case. Blast-as-exhibit can only suggest it; experiencing the historical materiality of the book can’t even begin to substitute for reading it – even in non-facsimile reproduction.

Likewise, the materiality of the traditional exhibit space doesn’t even evoke, let alone “recreate” the rebellious, radical spirit and context of the wartime exhibitions. The Penguin Club is a case in point: the Club had been founded shortly before the 1917 Vorticist Exhibition by Walter Kuhn, one of the progenitors of the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, who put on the influential 1913 Armory Show that introduced Duchamp, and Hopper, and Kandinsky, and the post-Impressionists – among many others – to American audiences. The club was a gathering place for modernist artists rebelling against the constraints of academic art, including Man Ray, Francis Picabia, and Joseph Stella. The club held exhibitions, put on costume parties and satirical theatrical productions, offered classes by its members to its members, and encouraged criticism, discussion, and debate. The sedate blue and cream walls of the exhibition don’t begin to capture the frenetic environs from which Vorticism emerged and in which it perpetuated itself. Mad Modernism indeed.

Which is to say – by all means you really must go to the exhibit if you are anywhere near Durham, Venice, or London. Read the wall tags, admire the materiality of the art, and marvel at the lost-but-now-am-found paintings. But be sure to flip through the facsimile edition of Blast and the superb exhibition catalog, too. Otherwise you’ll have seen Vorticist art, but missed what makes it Vorticist.