After three installments criticising Hergé for rampant racism and xenophobia, I uneasily picture his ghost appearing before me, with a quizzical smile.

« So, » says the ghost, « you’ve really dragged me through the mud, eh ? But what about yourself, Alex? Are you a racist?”

“No!” I answer. ”No, but…”

New York, Washington Square Park. I loiter around a chess game – I’m a rotten player, but I enjoy it as a spectator sport. Somebody grabs my arm—a muscular young Black man. I tense up with a fight-or-flight boost of adrenaline…

“You want a game?” he asks.

He didn’t want to mug me, he wanted to play chess.

Many another middle-class, middle-aged White man can attest to such embarrassing moments, where — despite professed liberalism– racist instincts seem to kick in at the worst times. It’s good that our conscious selves master our subconscious. The fact is, for one of my generation (I was born in 1954), urban African-Americans were synonymous with danger; an unofficial apartheid divided the city; and despite the fact that I was never hurt or even threatened by a Black man (the few times I was mugged were by Whites), I had internalised this detestable racist prejudice, one that went unspoken

Yet, would I have reacted the same had the incident occurred in Paris? I doubt it.

I was born to a French father and an American mother, growing up bi-cultural in America with long stays in France, where I now live. Like many bi-culturals, I have something of a split personality: there’s an American Alex and a French Alex.

French Alex has no doubt internalised quite different prejudices towards Black people. Consider this poster for a chocolate drink known to all French kids:

That soldier is a Tirailleur Sénégalais, one of hundreds of thousands of colonial soldiers sent to the front in World War One. Note his joyful laugh, over his exclamation “Y’a bon!”, which can roughly be translated as “Sho’nuff good!” The slogan is still heard as a racist taunt.

This was the French cliché of the Black man: a merry, childlike creature eager to serve his master. And I wonder if somewhere deep in my subconscious, that stereotype shamefully thrives.

(The image itself is still used:)

This is the context in which we should consider Tintin au Congo, and Hergé’s various racist lapses: they won’t in themselves convert a kid to racism, but they will confirm the mentally and morally lazy stereotypes that pervade every culture. And it’s hard to underestimate the ubiquity of Tintin in Europe. So, the librarians who remove Tintin au Congo to the adult stacks are doing their duty.

Myself, I got a bit of a jolt reading Tintin en Amérique. Even as an eight-year-old, I knew this America was just a comic fantasy:

…and no American I knew was remotely like the greed-crazed, thuggish citizens depicted therein.

I was, for once, at the sharp end of Hergés stick.

So, Tintin to the incinerator?

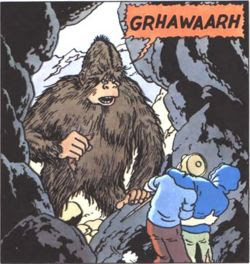

No. Other powerful and positive forces of Hergé’s approach to the Other are the attraction and wonder of foreign lands, foreign people. How many youths have set out to explore the world inspired by Tintin? And aren’t the values embodied by the plucky little reporter worthwhile ones—courage, loyalty, justice?

Besides which, the Tintin albums are simply wonderful yarns, crammed with suspense, comedy that is often uproarious, lovely art. They are about as fun as comics can get.

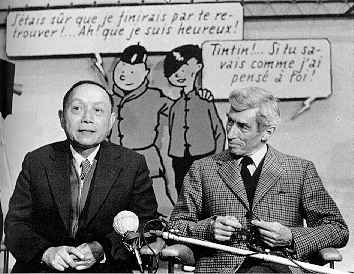

As for Chang, the young student who opened Hergé’s eyes to Chinese civilisation, he returned to Shanghai in 1936 to open a drawing school, which he managed for thirty years. He was purged by the Cultural Revolution, in which he suffered badly. Hergé never stopped trying to help him, and finally was able to bring him back to Belgium in 1981. The two friends were speechless at their reunion, 44 years after their separation.

Herge and Chang in 1931…

…Chang and Herge in 1981.

Let’s conclude where we started four chapters ago : with Tintin au Congo.

How do Africans feel about it?

It is, in fact, a perennial seller in Francophone Africa. Hergé was delighted that it was serialised in 1969 in the prestigious African Zaïre magazine.

That may sound like another depressing example of internalising one’s oppression…but not so fast. Here’s what Zaïre had to say about the strip:

“If certain caricatures of the Congolese people in Tintin au Congo make White people laugh, they also made the Congolese readers laugh because they found plenty to mock in the White man who saw them that way!”

In other words, they are laughing at, not with, the whites.

Three examples of African appropriation of Hergé’s imagery:

Sculpture from Kinshasha, Zaire

Kinshasha street mural

From Benin: Tintin, Congolese, and a missionary.

All Tintin art and images copyright Moulinsart

The entire Tintin in Otherland series is here.