(Concerning Harvey Kurztman’s EC War Comics)

A Reply to R. Fiore reprinted from The Comics Journal #253 (2003) Blood and Thunder Section. The reply is preceded by scans of Fiore’s response to my initial article. These scans are reproduced with Fiore’s permission.

I will respond to R Fiore’s first few statements by reproducing an edited version of my response from the TCJ message board:

I don’t think my statements in the essay deviate substantially from Fiore’s comments above. I single out a number of stories from MAD #1-20 for praise including a Krigstein story and follow this up by citing three Johnny Craig stories which manage to rise above the dross. However, whatever Bradbury’s own views on the subject matter, I still prefer most of Bradbury’s original prose to the adaptations. As stated in the essay, I do not have much argument against a select few of the early MAD stories being chosen the highest forms of comedy as yet produced in comics. It is the wholesale embrace of the early MAD issues that I’m arguing against

The films and books mentioned in the essay were chosen for easy recognition and their generally accepted levels of quality. I have no difficulty in naming many other modern books of lesser renown (and reputation) which far surpass the Kurtzman war stories in ability and passion: Mo Yan’s Red Sorghum, Jonathan Safran Foer’s Everything is Illuminated, Hikaru Okuizumi’s The Stones Cry Out etc. Further, I will go on record as saying that I find Tardi’s It Was the War of the Trenches superior to the best of the EC war stories.

As Fiore states in his letter, the orthodoxy within the Western comics sphere is that the Kurtzman comics are the best war comics ever made. All these meandering discussions will do not one bit to change this fact. Kurtzman certainly is one of the standards as far as war comics are concerned but he is an unacceptably low standard by which to gauge the genre in my view.

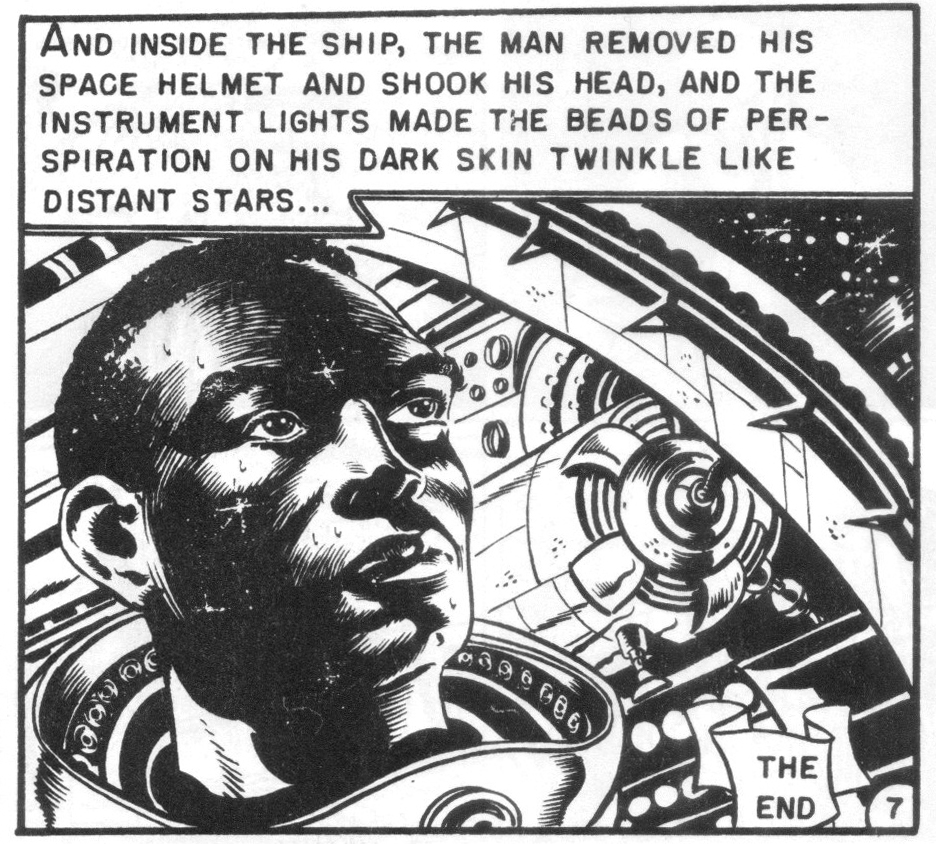

What logic is there in rating the EC War Stories over Palestine or Safe Area Gorazde except some misplaced sympathy for the backward aesthetic and cultural values of comics of a certain vintage? It should not be our concern if the practitioners of a certain period in comics did not have the imaginations or ambition to think beyond the accepted boundaries of their chosen livelihood. There were numerous cultural precedents for superior, honest work on war before that period.

The difference between the majority of the EC War stories and modern war comics is that, in comparison to the great works of war literature (and film), the latter are recognizably possessed of the same purpose and qualities we expect of the finest art. Neither of these works by Sacco may be on equal footing with Catch-22 but both possess that element of artistic ambition and maturity which has characterized many worthy artistic endeavors over the centuries. Kurtzman’s “Big ‘If’” and “Corpse on the Imjin” manage to engage the reader at that level but neither have stood the test of time in terms of their emotional complexity or their meditations on reality and truth.

***

R. Fiore’s letter demonstrates that he is either bereft of comprehension skills or a pathological liar. His willful misrepresentation of his opponent’s views both here as well as on the TCJ message board (placing words in their mouths as it were) indicate a steep decline into critical indolence.

Fiore tries to mislead his readers by suggesting that I am of the opinion that “Kurtzman and the EC artists should not be considered superior cartoonists to Joe Sacco just because they drew comics better.” Nowhere in the article do I even suggest this. Rather my dispute with many of the EC artists is that drawing well (and this is certainly not beyond dispute) is just about all they did with any level of accomplishment. Fiore may be anxious to dump content, narrative and dialogue into a bottomless pit reeking of nostalgia but I certainly am not.

It is telling that Fiore considers my description of the EC war line as children’s comics a form of condescension. In so doing, he totally ignores my statement that immediately follows this labeling in which I state, “I do not say this in a derogatory way, but to set out discussion of these comics within the proper context.” My use of this limitation was, therefore, not meant so much as an insult (though it would certainly be perceived as such by an EC fan who has always considered the EC line as pretty “grown-up”) but as a tool for judging them fairly within an appropriate framework.

Fiore, it would appear, has a latent disregard for children’s books despite his protestations to the contrary. In my view, comics crafted for children and comics crafted for adults must be judged using different criteria. The exact nature of these criteria is not within the scope of this reply, suffice to say that when it comes to children’s literature, a proper account must be taken of their accessibility (both emotionally and intellectually) and limitations. A work that does not meet or work within these criteria must be deemed bad children’s art. A comic prepared for an adult will therefore often fail miserably as art for children. It is precisely within the parameters of children’s literature that a few of Kurtzman’s war stories can be deemed of some merit.

As for my use of the word “juvenile”, readers will find that only once in the essay do I use this word and this is at the beginning of the essay when I am assessing the output of EC as a whole. When I label them “juvenile”, I mean that they were silly and immature. While it may come as a surprise to Fiore, I doubt that looks of stupefaction will greet my suggestion that there exist strange things known as “mature” children’s books. These are books that are considered and fully developed, and which speak to children in ways that are sometimes deemed inappropriate by an overprotective society. This is the reason why I quote Walter Benjamin in my essay as saying, “Children want adults to give them clear, comprehensible, but not childlike books. Least of all do they want what adults think of as childlike…” Benjamin was writing in an era of different “moral” standards but his words retain their significance even in this day and age of ever shifting moral boundaries. The problem is that Kurtzman failed so often even within these parameters, namely what is useful and relevant for the minds of 14 year olds.

In yet another deft act of conjuring, Fiore suggests that I have denied Kurtzman the “title of artist”. This is pure hysterical bluster. The reality is that my criticisms of EC have never centered around Kurtzman’s status as just that but rather the exact quality of the art works he produced. Truly, it is a sorry day when the esteemed critic’s rhetorical skills are coupled with an endless stream of lies.

Fiore’s next deception is to accuse me of failing to articulate that “quality” which is missing from the Kurtzman’s output. Yet even the most slothful reader need only turn to the “War Comics” section of my essay to see that I have provided quite a few details concerning my objections to EC. Fiore, in his geriatrically-imbued arrogance, ignores my points. Within the best of my capabilities, therefore, I will reiterate and expand on what is lacking in Kurtzman’s war stories and why I consider some of these inferior to Tardi’s It Was the War of the Trenches.

In the essay, I provide a short list enumerating the deficiencies which pepper the EC War line. (It is not a definitive listing but it will serve as a skeleton upon which to base further discussion):

(1) Jingosim (“Contact!”; which Kurtzman himself admits was “pretty dreadful stuff”)

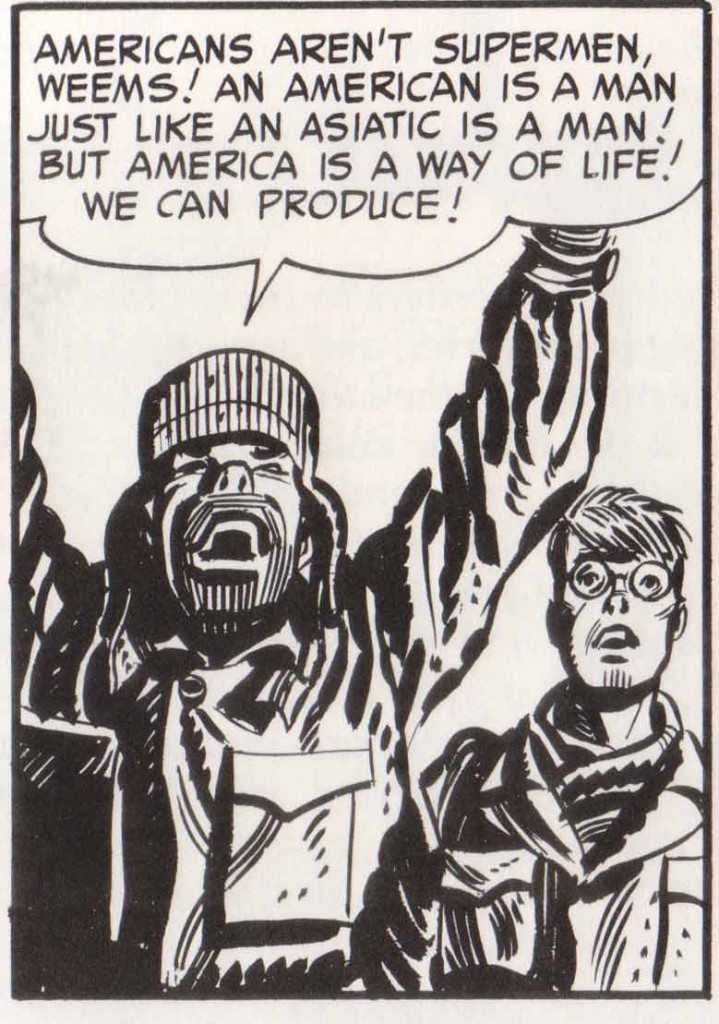

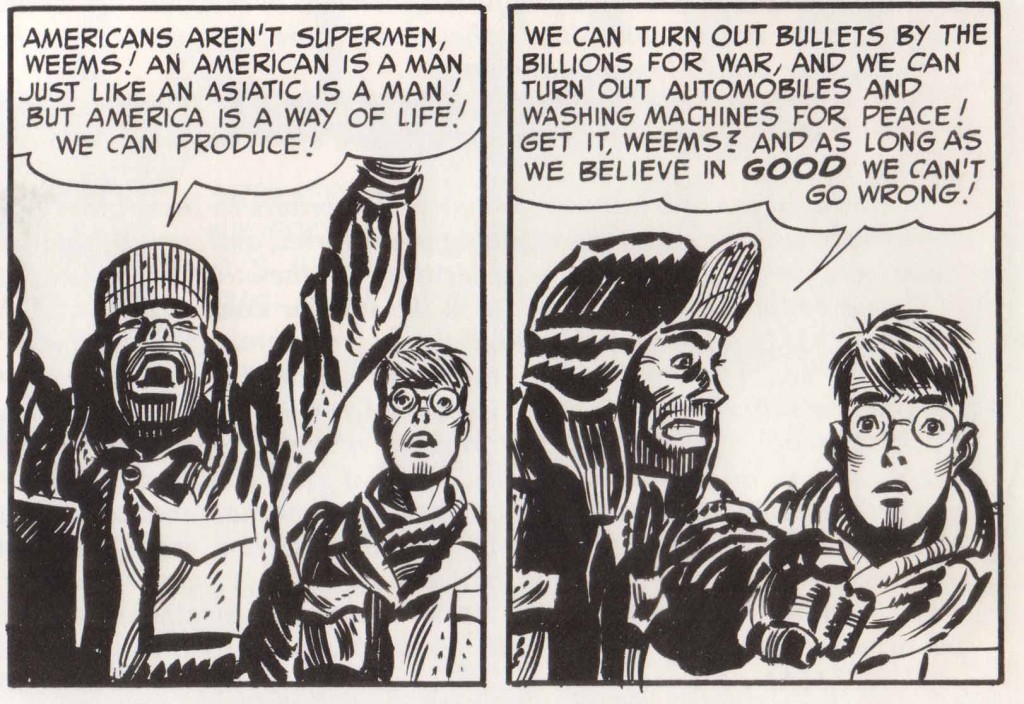

“Contact” is a story about a surprise attack by the Chinese on an American patrol. In the course of the story, we see the American soldiers mowing down the communists with great efficiency after an initial shot by those sneaky communists leaves the lieutenant in charge of the patrol quite dead. Some of this is done with great flair as when the Sergeant opens fire in a darkened tunnel creating momentary lighting effects in otherwise darkened panels. Amidst the chaos, a young soldier who is saved by his superior asks in wide-eyed fashion, “What’s the good sergeant? There are hundreds of them…and there are just two of us!…How can we ever hope to win against so many Chinese? There are ten of them to every one of us!” The sergeant replies, “I’ll show you how we’ll win, Weems! Look up there!” He points up to a T6 observation plane. Cut to a command position where a flight of F-86s and a column of tanks are called in. They proceed to bomb the living daylights out of the enemy. The Chinese are annihilated. Without a trace of irony, Kurtzman has his sergeant exclaim, “Americans aren’t supermen, Weems! An American is a man just like an Asiatic is a man! But America is a way of life! We can produce! We can turn out bullets by the billions for war, and we can turn out automobiles and washing machines for peace! Get it, Weems? As long as we believe in good we can’t go wrong!”

End summary. Now you would think that a story of this flavor would be a prima facie case of pretty abominable propaganda but it would seem that Fiore is quite happy to swallow this kind of bullshit whole.

(2) Dramatic draftsmanship and intelligent structure illustrating inconsequential content (“Thunder Jet”, “F-86 Sabre Jet!”)

Both of these well known stories are beautifully illustrated with planes delineated in clean and precise Toth-ian geometric minimalism. “Thunder Jet” purports to provide the reader with a ride along with the pilot of a Thunder Jet through ‘Mig Alley’. It seeks to communicate the concerns of said pilot with regards a perceived technological and skill gap. In the story, the Thunder Jet patrol spots an enemy train convoy and bombs and disables it. They meet some Chinese Migs, beat the shit out of them because they’re “being flown by kids…no formation, no nothing! They come up, every day, like a class room!” The patrol returns to base and you (the pilot, as the story is partly told in the first person) emerge from the plane as the narrator solemnly declares, “And as you finger the torn aluminum, you think of the 20mm cannon the Migs have! And then you think how the Migs go faster than you, and you think how the Migs outnumber you. And you think of that classroom in the sky! And then you think…We’d better do something, soon…pretty gol-darned soon!”

While this story displays a high level of achievement artistically, its narration flounders in insipid hard-boiled mannerisms which would not look out of place in a modern day superhero book. The story is devoid of any recognizable human emotions be they fear, remorse or courage. Maybe there’s a whiff of arrogance but not much else. Nothing beyond a plain stating of the facts—in other words, it’s a technical manual empty of human interest. If the work is assessed as a tale of adventure, the reader will search in vain for evidence of heroism or any trace of visceral excitement. It is a pleasure to look at and that is all.

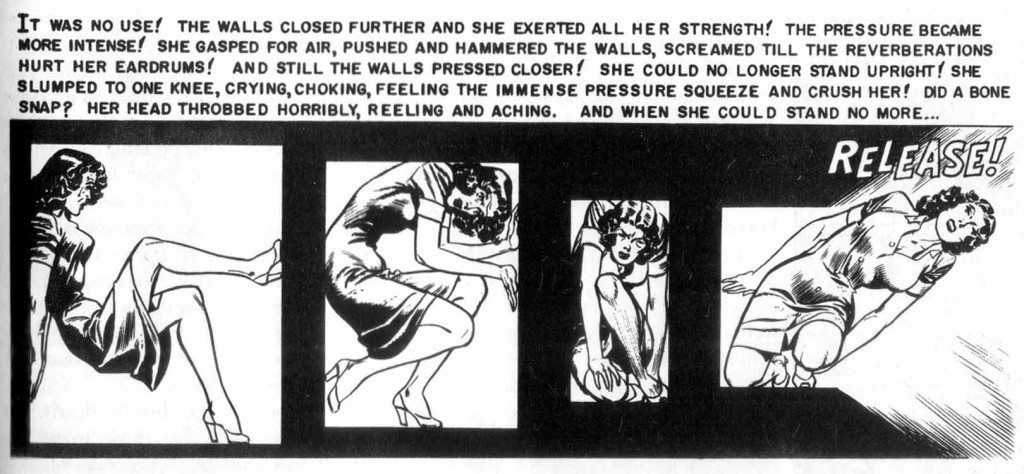

(3) Exquisitely dignified corpses (“The Caves!” from the Iwo Jima issue)

“The Caves” is an interesting story because its intent may seem fair minded and noble. The story starts with some portentous dialogue: “…and amongst the boulders and ravines, lay the sinister constructions formed by the hand of man…The Caves!”. The story concerns a Japanese foot solider who entertains treasonous thoughts about betraying his emperor. In essence, his crime is that of planning to stay alive while others choose death over the dishonor of surrender. Among other things, the story attempts to relate the not unheard of conflict between Japanese foot soldiers and the high minded ideals derived from bushido demonstrated by the officer class. It ends in a sort of positive light when the Japanese foot solider is demonstrated to have regained some of his honor within his own fixed parameters of reference (he kills himself in a Kamikaze-style charge).

In this story, Kurtzman shows some willingness to extend a degree of humanity to the enemy, something he was a tad more reluctant to do in the case of the danger posed by North Koreans and Chinese in the more contemporary Korean War. The difference is the distance provided by the passage of a few years.

With all these factors going for it, one might honestly ask why this story remains so utterly unconvincing. Why does the reader remain thoroughly unmoved by the condition of the Japanese protagonist? For one, there is no context for his betrayal of his culture’s values. We are not made to understand or perceive the awe with which Japanese infantry men often looked upon their officers or the reasons for their almost unquestioning obedience. The Japanese officer might just as well be an insane Allied officer as far as the story is concerned. We don’t understand the depth of his betrayal or cowardice and we therefore do not care for his predicament. Empty of both emotional connection and cultural information, it reads like a trite narration of a war time snippet. Kurtzman had no understanding of the Japanese he was portraying and failed in this nobly intentioned depiction of the enemy.

While “The Caves!” fails quite completely in its understanding of the “enemy”, I also chose this story because of its conspicuous falsity in pictorial representation. I’m not only talking about the failure in mere technical details like the overly enclosed space of the cave which makes the infantry man’s survival of several grenade blasts next to impossible but also the failure to represent the true horror of men throwing themselves into the arms of the enemy and hence death, and the truly awful consequences of a close quarters grenade blast. These shortcomings have a direct bearing on the effectiveness of the story. With death made so eminently easy on the eyes, there seems no reason for the infantry man’s cowardice. Where is the courage inherent in such a sacrifice? Why the vacillation? If we do not feel his dread, we do not journey with him through his resultant emotional turmoil.

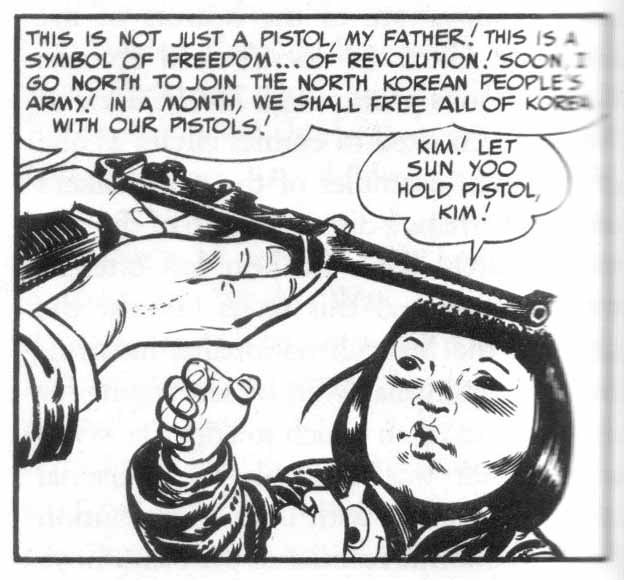

(4) The poverty of the enemies’ beliefs and the failure of their resolve (“Dying City!”)

(5) Sanctimonious depictions of the plight of good, honest, salt of the earth Koreans (Southern presumably; in “Rubble!”)

For reasons of space, I will allow interested readers the pleasure of exploring the catalogue of half and one-sided “truths” depicted in the above two stories.

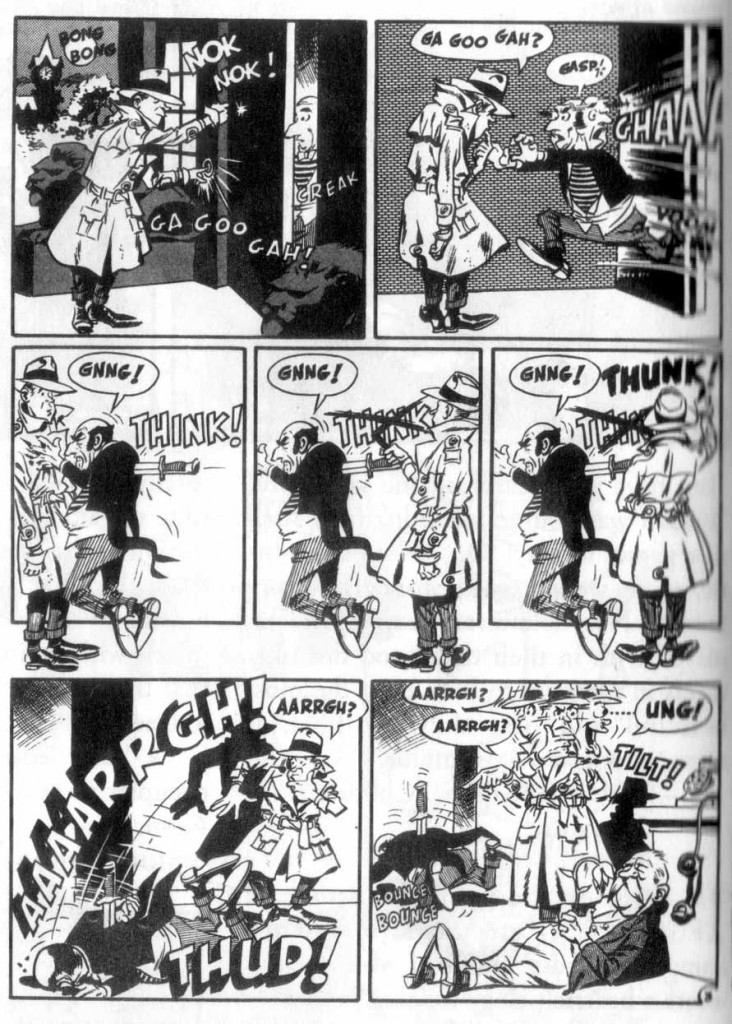

(6) Retribution for cowards (“Bouncing Bertha”), traitors (“Prisoner of War!”) and grinning, nefarious enemies (“Air Burst”).

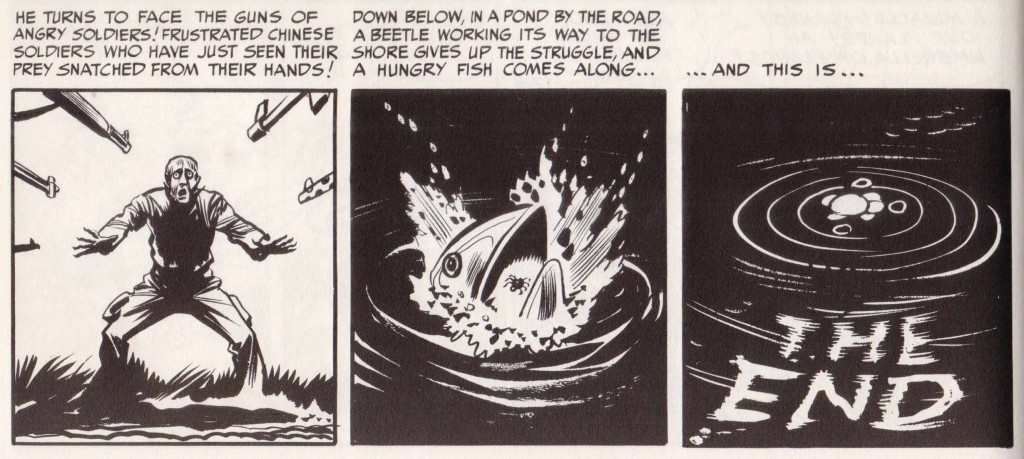

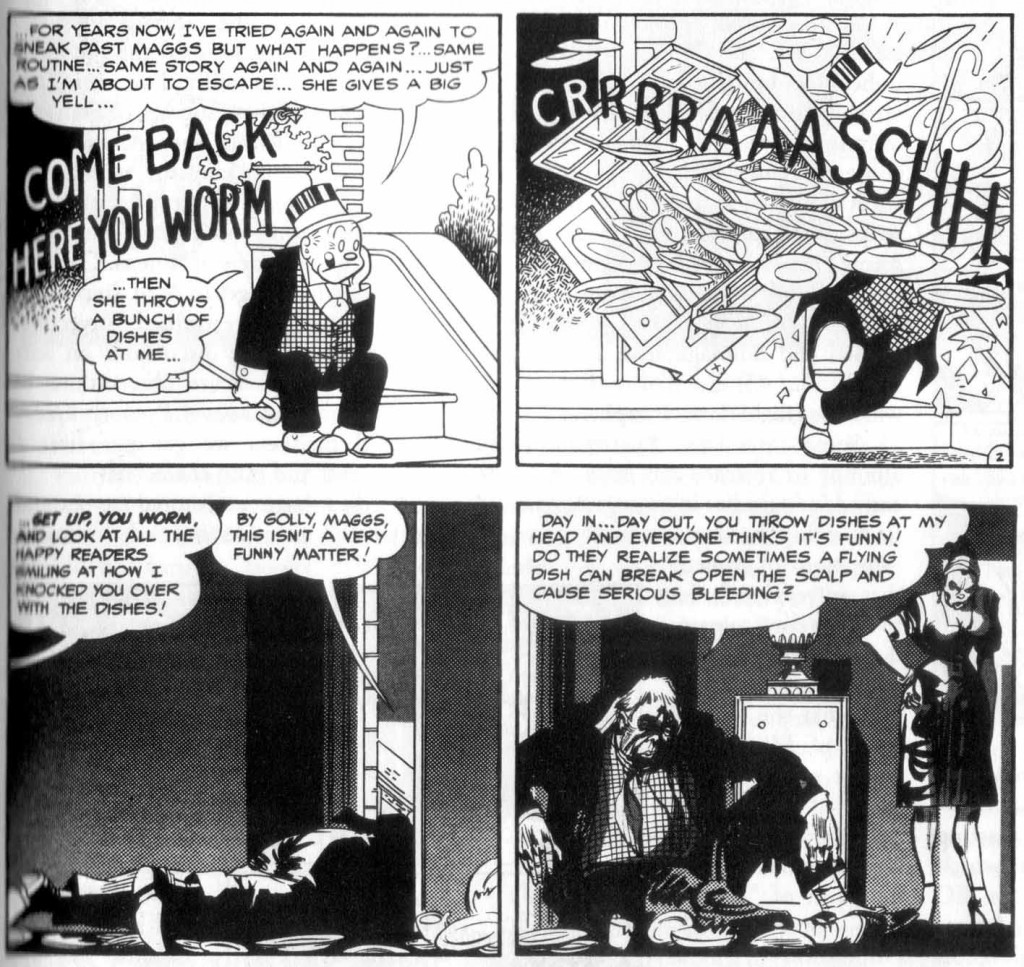

In the opening sequence of “Bouncing Bertha”, a bug struggling on the surface of a pond is compared with man — “…and yet, that little bug has enough sense to keep struggling…to keep fighting and to have hope till the very end. Even though he doesn’t know how he’ll save himself! It’s just like people!”. In the story proper, a tank crew meets with an accident, are deprived of their tank and find themselves behind enemy lines during the Korean War. While most of them decide to stand and fight, one of their number, PFC Allen, deserts and decides to surrender to the enemy. The heroic crew is finally saved by an air strike and an airlift via helicopter while the craven coward (and he is certainly drawn, somewhat predictably, with villainous, slovenly features) is left to the mercy of the angry Chinese.

What we have here is a crude extension of the black and white values propagated by the EC Horror, Crime, and SF titles where every villain gets their just desserts and where noble acts are rewarded. Fiore says that I have somehow misread Kurtzman’s purpose here. He suggests that I have inserted the false theme of cowardice where the story’s actual focus is that of the concept of “struggle”. But Fiore’s faculties are blinded by his passion for Kurtzman. His idol’s deployment of the word “struggle” is inextricably linked with the concepts of loyalty and courage. Fiore wants us to believe that Kurtzman was focusing on something amoral and existential but the denouement of the story suggests otherwise. Kurtzman is really only interested in a particular form of struggle—the “good” type—one which is plainly linked with faithfulness and bravery.

If Kurtzman had meant only to illuminate the concept of man’s “struggle”, he would have chosen a dramatic situation which was less clearly black and white. Instead of muddying the waters, he would have chosen to have the traitorous Allen survive rather than his more loyal comrades. For Allen also “struggles” in his own way, he clearly wants to live and will do anything to survive his situation. He chooses the rather risky avenue of surrendering to a somewhat unpredictable enemy and is willing to buck the trend of stalwart courage demanded by society. His death can only be seen as the result of a lack of bravery. Allen only fails to “struggle” for his country and his fellow soldiers. His crime—a deplorable brand of cowardice in the eyes of his fellow soldiers.

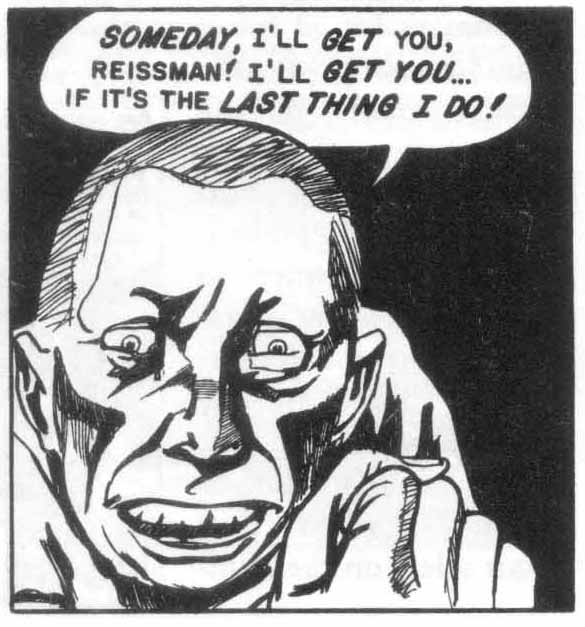

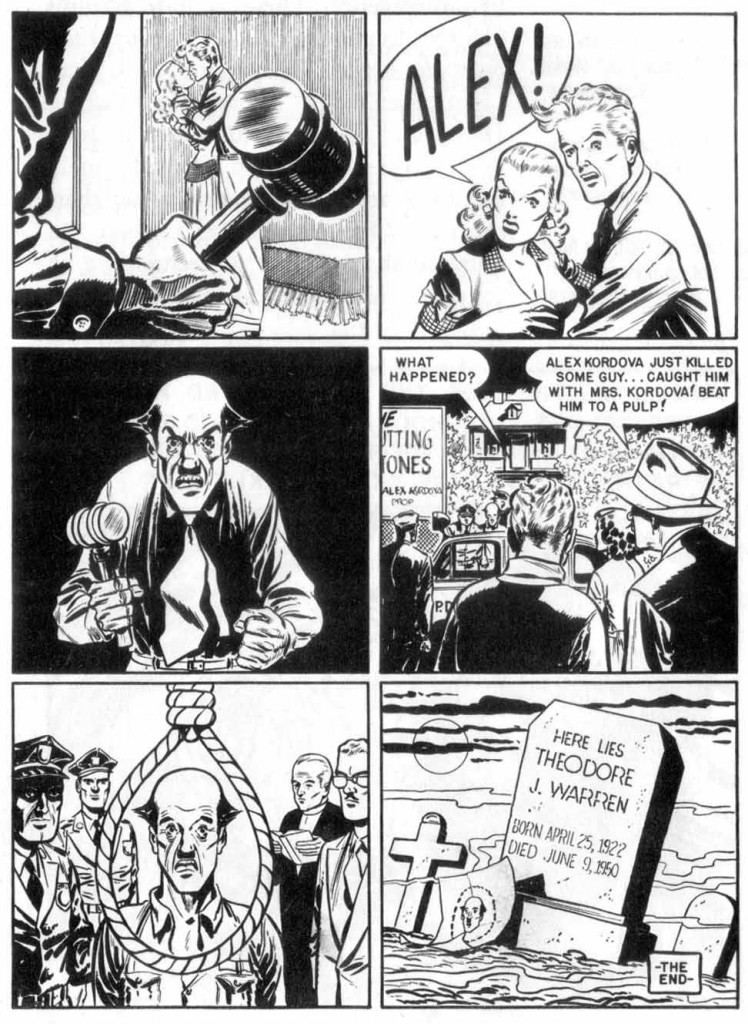

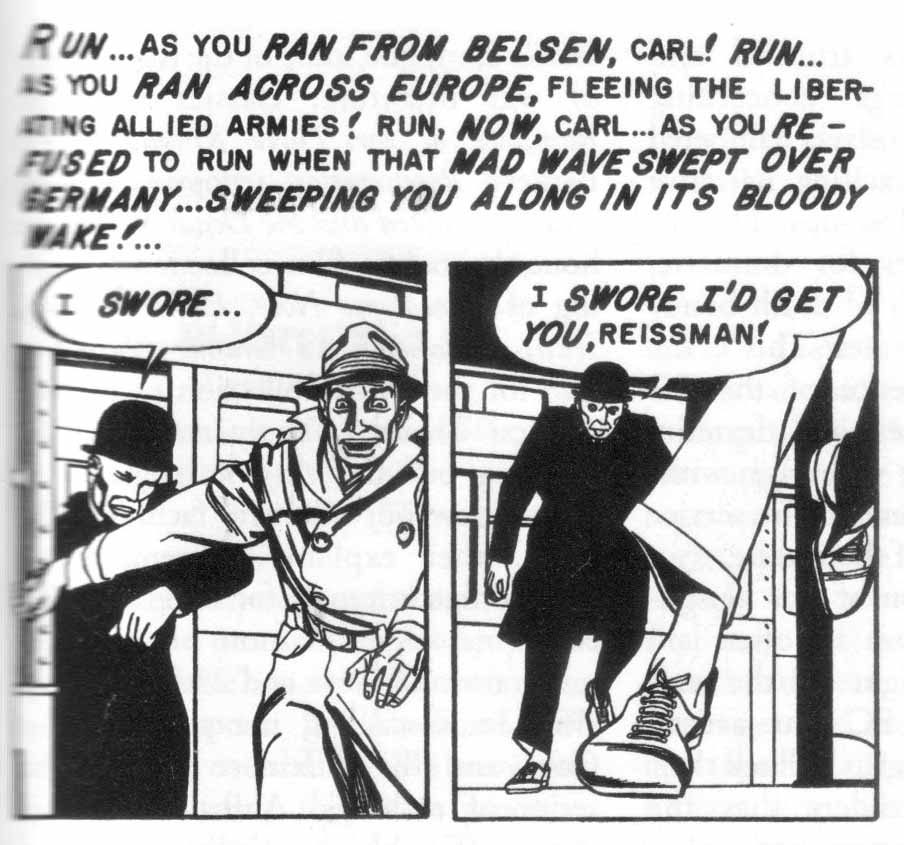

In “Prisoner of War!”, a group of American soldiers is taken captive by the North Koreans. The not too subtly named Benedict—who is seen to have a vile, insane look on page 2 of the story—cozies up with his North Korean guard and even helps him track down his comrades when three of the prisoners try to escape. The three, however, do manage to evade capture and, while recuperating behind their own lines, hear a retrospective account of how Benedict is killed by his North Korean captor during a summary execution of American prisoners.

Yet again, this story represents a return to the retribution ethos of the horror, science and crime titles. On this occasion, it is partially “softened” by the fact that the rest of Benedict’s non-traitorous comrades also die in the same ignominious way. The traitor’s end is, however, more focused and wretched because he is killed by the very person he was sucking up to. He gets his just desserts for being a turncoat (it never pays to be a turncoat in EC-land). Like many of the other EC stories, this is a conception of humanity and reality that would not look out of place in a Silver Age superhero comic.

“Prisoner of War!” is also firmly locked in a 50s time warp both politically and culturally. The communists, as in many of the other EC stories, are seen only as inhuman beasts; distorted and corrupted in the best tradition of political propaganda. While it is undoubtedly true that the North Koreans were guilty of committing numerous acts of democide, we of course hear nothing of the equally wonderful massacres by the squeaky clean South Koreans and American GIs. Clearly such insights and journalistic integrity were beyond Kurtzman (and many others of that time) but this propensity to swallow the party ethos hook, line and sinker must suggest that the work is bereft of the insights which are the hallmark of the best literature. The story’s usefulness as a historical document extends not so much to its portrayal of the realities and complexities of the Korean War but the prejudices surrounding it. The modern day reader is often swayed by the more realistic setting and the less fantastic turn of events in the Kurtzman war stories but the underlying falsity is clearly in evidence.

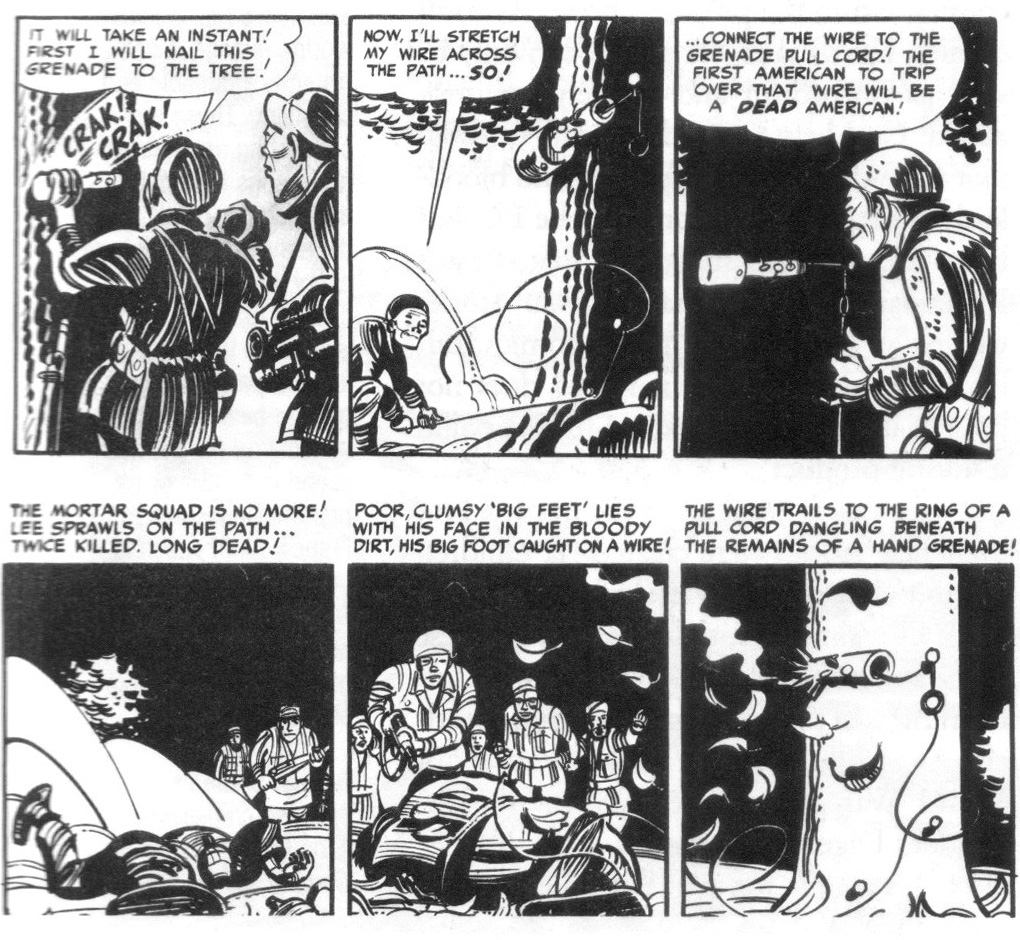

“Air Burst” (Frontline Combat #4) concerns two Chinese mortar squad soldiers who find themselves alone after the rest of their squad is decimated by American air bursts. One of them, Lee, decides to set an explosive-tipped trip wire to kill any Americans who happen to follow their line of retreat. The two Chinese soldiers continue to use their sole mortar to assail the Americans but finally meet their match in a strafing fighter plane. Lee is injured but his comrade, Big Feet, manages to escape unscathed. Big Feet attempts to carry Lee to safety but then encounters a flight of American bombers which drop “surrender papers” on their position. Big Feet decides that they should surrender and retraces his step to surrender to the Americans. He forgets about the tripwire explosive device and kills them both in the process.

There are a number of ways to view this story. Those of a charitable disposition would suggest that this is a balanced depiction of the communist Chinese. Big Feet is depicted in a reasonably objective fashion. He tries to save Lee because of the bonds of friendship and, in his own simple way, realizes that the Americans offer hope and safety. He is defeated only by the calculating, malevolent Lee who is the cause of their misfortune (he is the one who sets the trap to kill the Americans).

Someone of a more critical disposition would suggest that this is unadulterated American war office hoopla. The story draws broad caricatures of the Chinese communists. On the one hand, there are the simple-minded natives who have been caught up in a war which they don’t really want to fight and, on the other hand, there are the nasty communists who are a danger to both us (the Americans) and themselves. Filled with the dividend of self-righteousness emanating from the conflict during World War 2, the story ends with the approach of the Americans whose generosity and mercy even extend to those horrible communists.

If Kurtzman’s purpose was to narrow the “humanity gap” between the American and Chinese soldiers, he can only be accounted to have failed miserably in “Air Burst”. An enemy who is seen to contemplate the death of a fellow American with pleasure would not have met with approval among his readership nor would it have reduced their inherent prejudices. There is a marked difference in the portrayal of the enemy here and that of Rommel (the “good” enemy) in “Desert Fox!”.

***

To end, I will look at the two stories which have come to represent the peak of Kurtzman’s war oeuvre.

“Big ‘If’” (Frontline Combat #5) is a story which relates, in flashbacks, the untimely end of an American GI (called Maynard) from a shrapnel wound. The formal and structural elements of the story have been cited most often for praise. Kurtzman makes liberal use of a three panel staggered close-up, a technique that is also used with great regularity throughout the war stories. The wooden devil posts which bookend the story provide a sense of impending doom as they fill the background in the small panels on the penultimate page of the story. The sound of a descending shell substitutes for the absent laughter of the same. On the final page of the story, the soldier’s face is wracked with agony in contrast to the grinning devil posts on the opposing page. The reader’s expectations are tautly held by the snaking narrative, the tension slowly building to a climax in which the reader’s barely held suspicions are made flesh in the form of a bleeding shrapnel wound

As an example of deft narrative technique, “Big ‘If’” remains an interesting case study. Yet it fails to match this achievements in terms of its emotional impact. “Big ‘If’” strives to delineate the fragility of life by throwing light on the fine threads of possibilities upon which life hangs. The protagonist is a man beset by unfathomable forces. It is an existential tale which could be transposed to a non-military setting without much difficulty (it has thematic similarities with Eisner’s “Ten Minutes”—from The Spirit Section Sept 11 1949— for example). Yet we do not feel for him because he is an enigma shackled by leaden narration, a disconnected collection of lines bemoaning his fate. There is little in his characterization which suggests that he is a fleshy human, nothing in his words to allow us to empathize with him. Each twist in Maynard’s destiny is rushed as a result of constraints of length thus diluting our sympathy with his final end. The choices he makes are insufficiently jarring or nuanced, his despair without context or meaning for the reader. In “Big ‘If’”, Kurtzman allows us to view the death of a soldier away from the dehumanizing aspects of mechanized warfare. It is one of his most valiant attempts at concentrating and humanizing mass conflict, but he falls short by a few degrees despite or, perhaps, partly because of his elaborate forms of artifice.

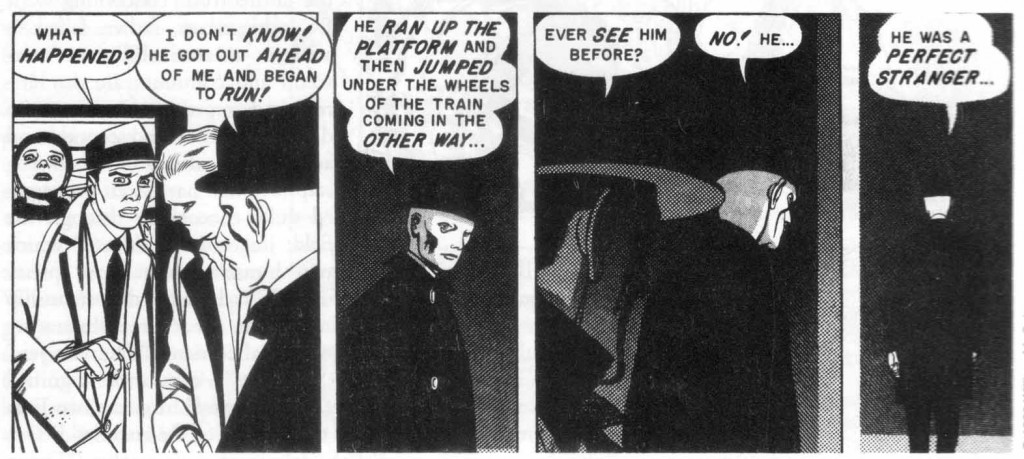

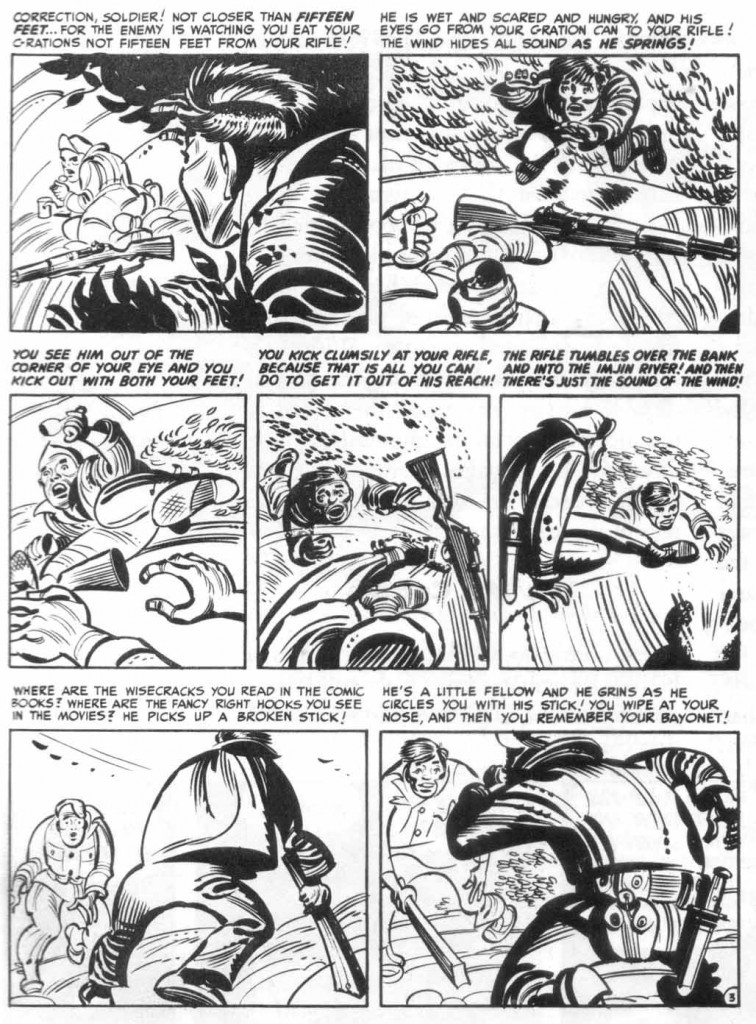

“Corpse on the Imjin!” (Two Fisted Tales #25) is one of Kurtzman’s most powerful war stories. There are few pages in the EC war comics as powerfully drawn and composed as the final two in this tale: the violent movement of the American solider as he drowns his enemy are given force by the use of the words “dunk…dunk…dunk” in the narration as well as the desperately clawing hands of his opponent. The intensity and concentration of the reader is brought to bear on the act of murder by the staggered close-up of the man’s last drowning breaths and then the gradual movement away from the floating corpse who remains, to the end, without name or origin. The entire incident is driven solely by bestial instincts and the final detached corpse as objectified as the inanimate cases and tubes which are seen floating down the Imjin at the start of the story. Artistically, “Corpse on the Imjin!” is short, sharp, and brutal and this is exactly what is required to communicate the act of killing both in war and in self-defense.

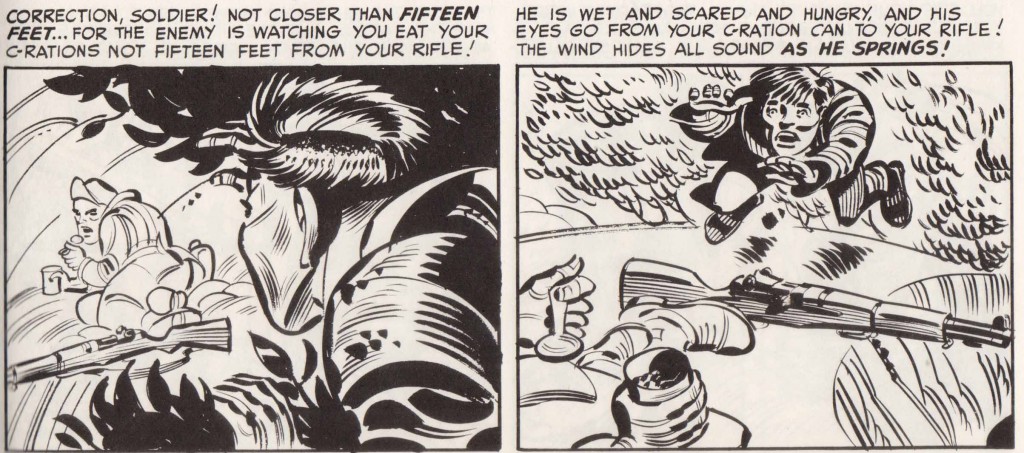

There is, however, a familiar dark cloud which sullies the experience. It is one that overwhelms almost all the EC line—the clumsy, redundant narrative. The fight scene on pages 3 and 4 is filled with burdensome text and there’s even more scattered throughout the story. Kurtzman (as in many of his other stories) felt a need to shove his point in his readers’ faces. Subtlety is at a premium. On page 2 of his story, he has his American soldier drive home his “moral” when he shows him thinking to himself, “Now with all the long range weapons, we can kill pretty good by remote control! And we never get closer’n a mile to the enemy!” This is naturally followed by close hand to hand combat with a communist soldier. Not satisfied with merely showing the enemy at close quarters peering over the American, Kurtzman finds himself locked into the narrative conventions of the time as he intones, “Correction, Soldier! Not closer than fifteen feet…for the enemy is watching you eat your C-rations not fifteen feet from your rifle”. On the final page of the story, rather than let us experience the full force of his artwork, he force-feeds us some insipid platitudes: “Have pity! Have pity for a dead man! For he is now not rich or poor, right or wrong, bad or good! Don’t hate him! Have pity…For he has lost that most precious possession that we all treasure above everything…he has lost his life!”

Kurtzman apologists and fans have been willing to forgive the avalanche of ham-fisted writing which marks most of the EC war line (this being but one example amongst many) but I certainly am not. They want to sweep these sins under the carpet, as if words are somehow irrelevant to the cartoonist’s art. When called into account, they plead historical context as if good writing was only invented during the late twentieth century.

In his letter, Fiore states that “unless you’re giving him extra credit for antiwar sentiment I don’t see that “War of the Trenches” is any better than the best of Kurtzman”. Frankly, I find it astonishing that Fiore is so enamored of Kurtzman’s comics that he will even stoop to making such a statement. Fiore has clearly suckled so long at the teat of “comicness” (the essentialist view of comics which seems to be the basis of all his criticism) that his taste buds have atrophied. His unwavering view that comics are “a crap form contaminated by art” has led to his wholesale acceptance of aging works of only modest aesthetic merit. This can be the only explanation for his blindness to the superior qualities in Tardi’s war stories and his desire to persist in wallowing in his sty of EC mediocrity (don’t forget, this is the man who once wrote, “Any discussion of EC has to begin with the horror comics, not only because they were the most infamous and popular, but because they may have been the best.” This before proceeding to wax lyrical on the aesthetic rewards to be derived from the EC hosts (The Comics Journal #60).

An argument for Tardi’s work over Kurtzman’s would fill another essay. Tardi’s work is richer in characterization as well as moral and psychological subtlety. It is possessed of an aesthetic congruity and consistency between the words and images that is largely absent from even the best of Kurtzman. Further, the war is more perceptively individualized than anything found in the EC war comics creating a greater degree of empathetic truth. The violence is exact, cruel and never an excuse for heroics. The overall artistic vision and undivided purpose of It was the War of the Trenches makes it superior to just about anything in the EC war line.

***

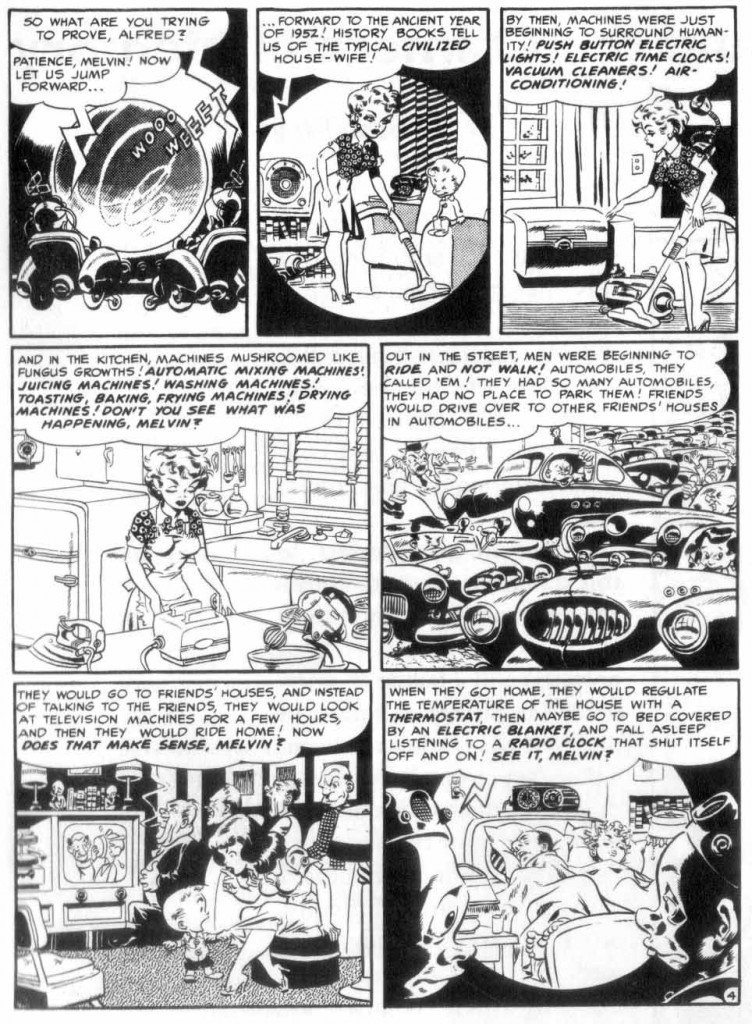

In his letter, Fiore writes, “what gives them [the war comics] their special quality is how he determined to do it. Kurtzman’s theory was that reality was far more interesting than the absurd fantasies war comics had engaged in up to then.” Fiore seems to be of the opinion that Kurtzman’s war comics represent some sort of unshakable benchmark in realism. This is a delusion. I have already enumerated a few of the fantasies that persist within the EC war stories. At best, most of them can be seen as ironic adventure tales to be read at bedtime under sheets with a torchlight. They almost never allow us to acknowledge any revulsion for the abomination that war has always been.

Not once does Fiore counter my claim that the overall weight of the stories in the EC war comics fall drastically short of the mark. Instead Fiore presents us with a few examples of Kurtzman’s realism in his letter thinking to deceive readers too lazy to peruse the comics for themselves. Yet even this very selective list—culled from the first few issues of Frontline Combat—presents a majority of stories that do not sustain any level of realism. Let’s take a look at what Fiore offers up in Kurtzman’s defence [for reasons of space, I will only consider a few of them]:

“As a platoon retreats in the face of the Chinese counterattack during the Korean War, they are pinned down on their way down a hill, and call in the Air Force to burn the enemy out with napalm. “

The summary concerns “Marines Retreat!” from Frontline Combat #1. The napalm attack is seen as a small explosion and the resultant carnage no more than a few innocuously drawn charred limbs gathered in a small corner of the third panel on page 5. If this is the reality and horror of a napalm attack, it is a wonder there’s such an outcry against its use. The napalm attack is followed by two pages of action which would not look out of a place in a boy’s adventure comic (yes, I know, that’s what the EC War line actually was) and a final brave stand by one of the wounded who in good old war comics tradition wants to cover for his comrades since he’s “finished”. If this is “realism”, we should all be so bold as to spit in its face.

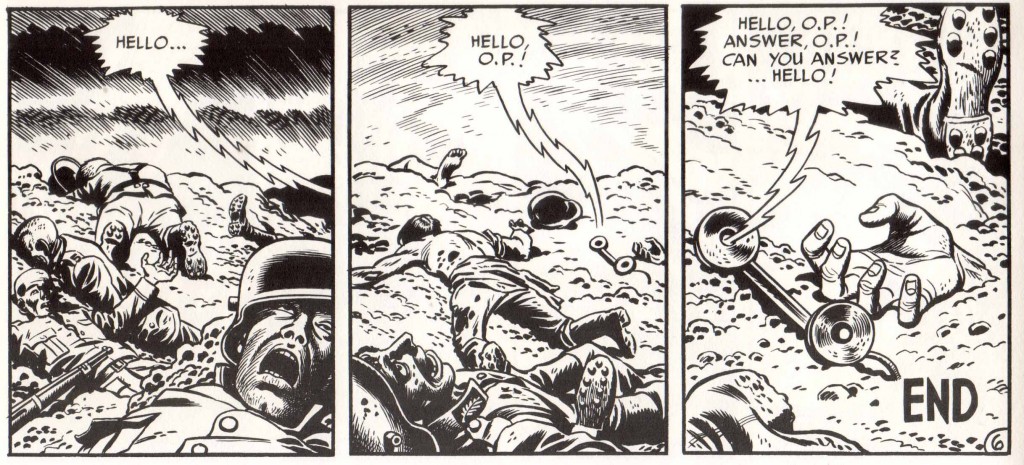

“The loan survivor of an artillery barrage on an observation post must call in another artillery barrage on his own position when it is overrun by the enemy.”

The scenario is drawn from “O.P. !”, (Frontline Combat #1) and tells the story of how a soldier assigned to an observation post sacrifices himself in the line of duty in order to hold off the Germans who have infiltrated his trench. In other words, it is one of a number of traditional brave, self-sacrificing soldier stories that pepper the EC war comics.

Still, this is one of the few EC war stories where the dead (who somehow still remain wholly intact after being pummeled by artillery shells) are seen to lie in something resembling an undignified position (the protagonist and hero—that’s clearly what he is—is buried underground at the end of the story). The EC artists may have paid close attention to the number of rivets on a machine gun but they almost always took a step back when it came to the reality of death and suffering on the battlefield. As a result, dispatching the enemy (and the whole concept of warfare) resembles something clean and efficiently humane, not something appalling and despicable to be resorted to as a last resort.

Another example Fiore cites is “Zero Hour” (which is also set in World War I) in which “a wounded soldier is caught on the barbed wire. The enemy allows him to stay there in order to demoralize his comrades and draw them out to be shot when they try to rescue him. After he has groaned piteously for hours, and three soldiers have been killed trying to rescue him, his own officer shoots him to put him out of his misery.”

In the Cochran reprints of Frontline Combat, Kurtzman is made to discuss the genesis of “Zero Hour”. In the interview, Kurtzman says he saw the scene in All Quiet on the Western Front and that it also appeared in “several war movies.” As with the Feldstein-Bradbury stories in the EC Science Fiction comics, Kurtzman is on firmer ground when he follows the example provided by his artistic predecessors. This makes “Zero Hour” one of the more “realistic” stories in the EC war line.

Since the scene in question does not appear in Remarque’s book, one assumes that Kurtzman is talking about Lewis Milestone’s adaptation. Returning to the source material, what we find in Remarque’s book is this: men scrabbling for food and luxuries, pages of just waiting, a feeling of sickness and loathing at the endless descriptions of amputations, decapitations and festering injuries which finally create a feeling of neurasthenia on the part of the reader. All told without hyperbole in an unsentimental, plain narrative voice.

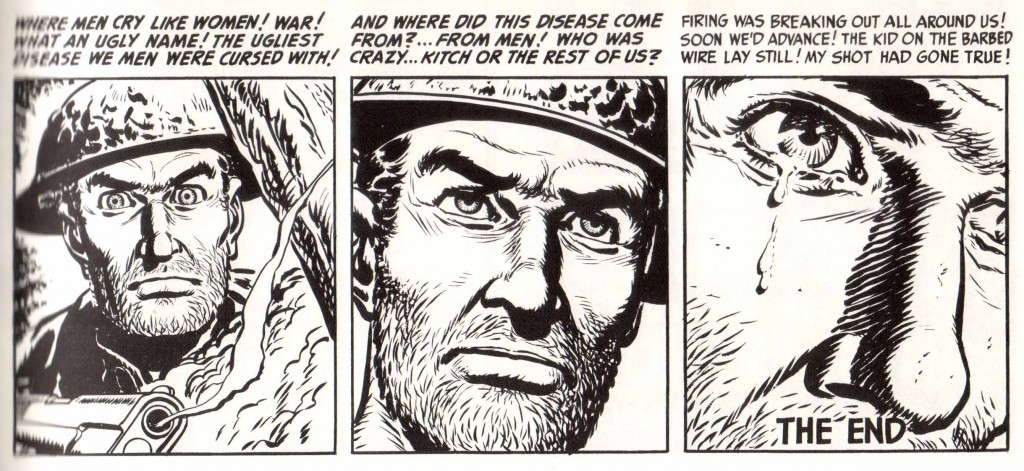

What we get from “Zero Hour” in contrast are some maudlin images of a soldier’s anguish. In the final three panels of “Zero Hour”, we get a gradual close-up of the sergeant before three tear drops mark this hard-as-nails soldier’s face. This is capped off by some truly idiotic narration: “War! What an ugly name! The ugliest disease we men were cursed with! And where did this disease come from?…from men!” If there is any truthful emotion or realism within this story, it is completely obliterated by Kurtzman’s heavy-handedness. If a work of art fails to elicit reflection on its presumed theme because of its narrative ineptness, one can only say that it has also failed a crucial test pertaining to its absolute quality. The resultant sappy entertainment has nothing to do with realism.

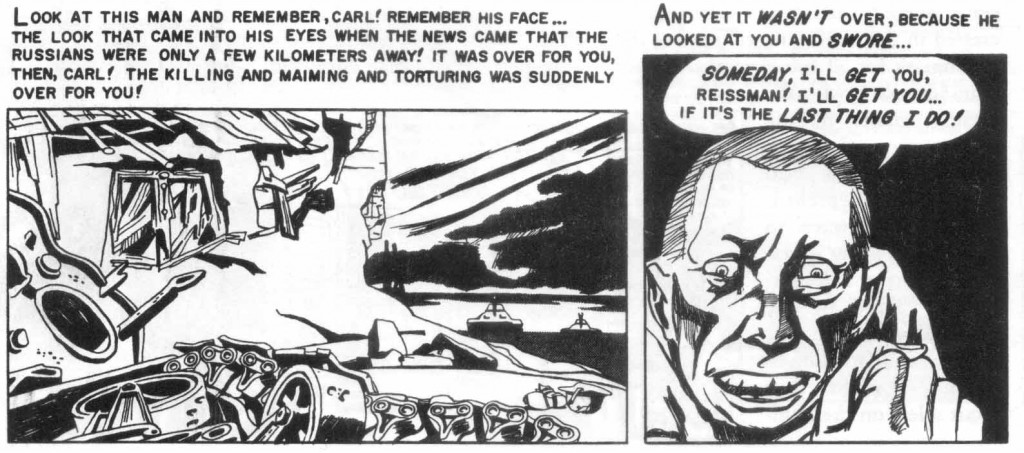

“Tales of the gallantry and dash of General Erwin Rommel are juxtaposed with scenes of Nazi atrocities, including scenes from the concentration camps, which Tong claims Kurtzman ignores.”

Fiore once again demonstrates what a poor reader he is with this statement. Frankly, it’s almost getting a bit undignified. Nowhere in my essay do I even suggest that Kurtzman ignores the Holocaust. In only one instance do I bring up the concentration camps (in particular Buchenwald) and in that instance it is only to illustrate the point that young readers are quite capable of assimilating such atrocities (whatever their more protective parents might think). “Desert Fox!” (Frontline Combat #3) demonstrates that Kurtzman was not totally at odds with this point of view and would occasionally overcome his squeamishness with regards violence to show true scenes of horror (“true” violence being reserved only for the pages of the horror comics). The page (drawn by Wally Wood) stands out because it is at odds with just about every other depiction of violence in the EC war lines. Fiore deceives his readers when he suggests that this page is somehow representative of the rest of the war comics. Further, this point does not even take into account the fact that the page is clearly meant to balance out (and deflect criticism) of the honorable depiction of Rommel in the story. The war atrocities are a side dish. It’s just one example of the kind of spineless artistic schizophrenia that inhabits many of the EC war comics.

“A submarine captain is stranded when his ship has to make an emergency dive. He is about to be rescued by an enemy destroyer, but is left to drown because his submarine surfaces to attack and the destroyer must sail away to evade it. “

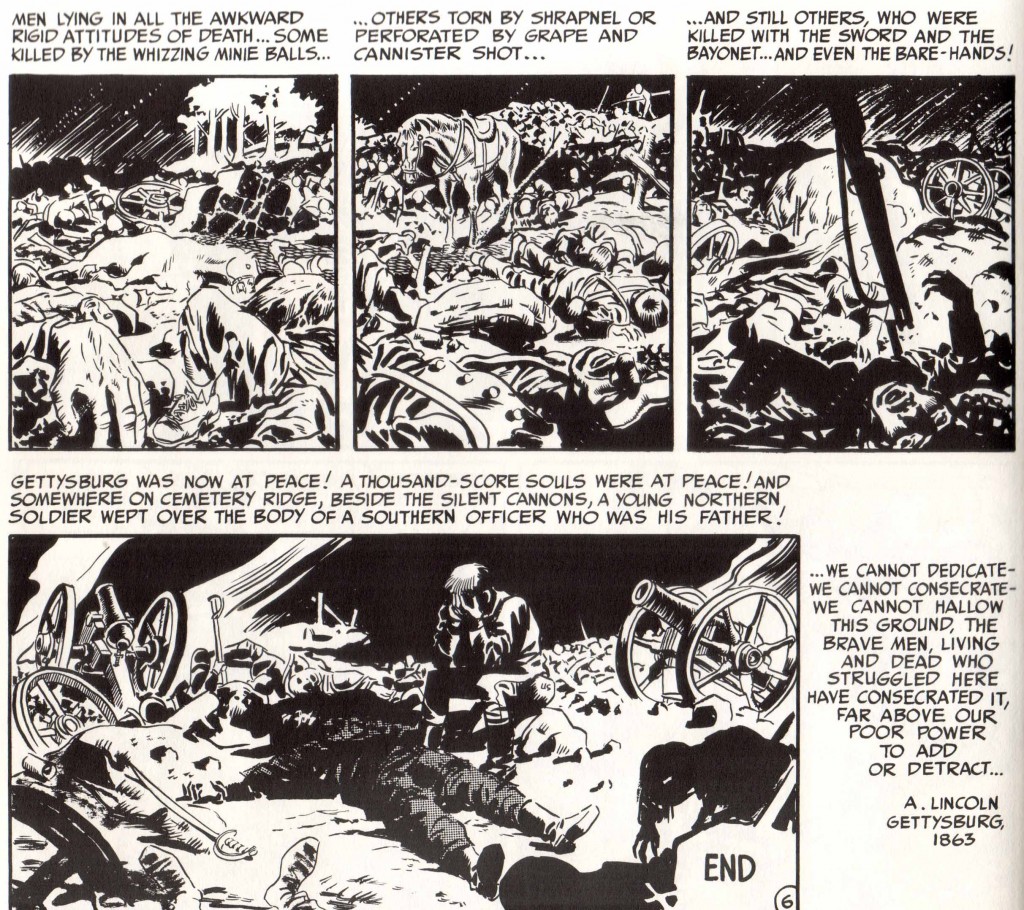

“A Union soldier at Gettysburg discovers that the Confederate officer he’s killed is his own father.”

“A French civilian notes the drab uniforms of the Allied soldier, and recalls how he and his fellow officers from the Academy insisted on wearing their colorful traditional uniforms in World War I and were slaughtered for their vanity. “

In my article, I suggest that the EC war stories are “gentle, dignified and bloodlessly pleasant” and that “they glorify by exclusion and by failing to relate life’s simple truths.” It is quite obvious from the few examples he chooses that Fiore believes he can counter my statements by demonstrating that Kurtzman’s war stories contain images of people killing each other and dying, as if this wasn’t an element in just about every modern day action movie.

To strengthen this somewhat defective point, Fiore points us towards two tales that once again demonstrate the EC writers’ deft hand at irony and the “shock” ending.

Both “Unterseeboot 133” (Frontline Combat #1) and “Gettysburg!” (Frontline Combat #2) care little for the realities of war. There are exciting explosions and people are knifed and killed. In short, they are mildly disguised adventure tales (masked with “historical authenticity”) striving to titillate their young audiences. “Gettysburg” in particular is a story obsessed with getting to its final twist ending. The war is merely a backdrop and an excuse for the denouement. A person glances at the dead bodies piled up on the final page of the story and hardly even registers them. They’re insignificant, just ink blots on paper without a trace of emotional meaning.

Fiore does Kurtzman a disservice when he suggests that “pacifism was not an option” during that period in the 40-50s. An artistic philosophy which dictates that the atrocities of war should be presented with unadorned, unmasked truth does not equate with pacifism. Further, he does not make a good case for his artistic hero when he writes, “Kurtzman’s sensibility is shaped by World War II, and assumes that in a world that breeds Hitlers pacifism is not an option.” I wonder if this is an inadvertent or reluctant unveiling of Kurtzman’s limitations. How are we to fully respect the works of a war artist whose vision does not extend beyond his immediate social circumstances and pressures?

The barely concealed secret about war is not that people die and that people kill each other but that they do so in ways which are thoroughly repellent. Most of the EC war stories on the other hand present themselves as mere candy floss. Further, there is almost never any adequate depiction of suffering within the EC war line which is strange considering that war is violence directed towards just that end. When you read books like All Quiet on the Western Front or, to take a more recent and less elevated modern example, Philip Gourevitch’s We wish to inform you that tomorrow we will be killed with our families (which concerns the Rwandan genocide), the overwhelming feelings are quite simply those of nausea, revulsion, and a very deep anger. We are left in no doubt whatsoever that war is horrible and not an insignificant backdrop to some contrived twist of fate.

If Fiore cannot differentiate between mere portrayals of violence and truthful, cohesive depictions of the same then that is his good fortune. He can fill himself with the masses of similarly half-hearted (if not thoroughly insipid) depictions of the “realities” of warfare which fill the book shelves and cinemas. I would suggest, however, that readers take note of this deficiency when he presumes to promulgate his inadequate standards to all and sundry.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.