BOSWELL: Why, Sir, it is bruited through all London that Garrick holds the pictorial efforts of our Mr Hernandez in the utmost esteem.

JOHNSON: Garrick, Sir, can go fuck himself.

***

Sometimes people disagree — NEWS FLASH, right? People disagree about politics, science, religion, sports, the weather, what it’s got in its pocketses…and sometimes they disagree about art. Indeed, as you may have noticed, people around here sometimes politely disagree with other people about art.

So what should you do when you disagree with someone about a work of art? I don’t mean “should you call them fanboys?” or “should you call them vaginas?” or “how can you best persuade them that, on reflection, everything you say is correct and everything they say is STUPID?“; forget about what you should do to the person you disagree with. I’m asking how you should treat your own opinion when you find someone who holds a different opinion.

My question isn’t how you should treat the reasons, evidence, arguments, etc. that they might put forward to bolster their opinion. Leave all that aside, too, and just consider the basic fact that they disagree with you. Is that fact, by itself, important enough that it should make you change your mind, if only a little?

Since the mid-2000s, this question has become a hot topic in epistemology — the philosophy of knowledge. Broadly speaking, there are two answers to the question:

(1) Resolution

and (2) Conciliation.

According to the resolute view, disagreement ain’t shit — you don’t have to do anything when you find someone who disagrees with you. You’re perfectly entitled to maintain your own belief exactly as strongly as you did before you learned that somebody disagreed with you; in other words, you can stand resolute. According to the conciliatory view, by contrast, disagreement is shit — it should make a difference to your belief. Exactly what difference, and how much, is up for grabs among philosophers who hold the conciliatory view; but they are united in believing that disagreement should make you at least a little less confident than you were before. (Stick with me; we’ll get to talking about comics eventually)

Here’s one way to think about what conciliation means. Picture all your thoughts as a big list of sentences written in your mental notepad. They might include:

2+2=4

The Earth revolves around the Sun

Caesar crossed the Rubicon

Barack Obama will win the 2012 US election

The moon is made of green cheese

2+2=5

and so on.

Some of these things you believe, and some you disbelieve. You believe some really, really strongly — like 2+2=4 — some less strongly — like, perhaps, the belief about Barack Obama; and similarly for the sentences you disbelieve. So now imagine that next to each sentence is a number between 0 and 1. 0 means “I think it’s definitely false”, 1 means “I think it’s definitely true”, and values in-between correspond to varying degrees of confidence. Now the list might look like this:

[1] 2+2=4

[0.999999] The Earth revolves around the Sun

[0.9995] Caesar crossed the Rubicon

[0.6] Barack Obama will win the 2012 US election

[0.0001] The moon is made of green cheese

[0] 2+2=5

On this picture, people disagree when they assign different numbers, or credences, to the same sentence. So maybe in my mental notepad, the sentence about Barack Obama has the number 0.6 next to it, whereas in Noah’s notepad it has the number 0.8 next to it. This would mean that I am less confident than Noah that Obama will be re-elected.

What conciliatory views say, in essence, is that when Noah and I discover our disagreement, we should revise our credences towards one another. Noah should be less confident about Obama’s chances, and I should be more — OTHER THINGS BEING EQUAL. (We’ll get back to this caveat shortly).

Another name some people sometimes give to the conciliatory view is the Correct View. And by “some people”, I mean “me”, and by “sometimes”, I mean “right now”. I call it the Correct View for the simple reason that it is the correct view.

The basic motivation for holding the Correct View is this: when you find someone disagreeing with you, and you have no reason to think you’re in an epistemically better situation than they are — i.e. you’re not any smarter, or more informed, or less drunk, etc. — then you really don’t have any reason to think you’re more likely to be correct than they are. So the mere fact that someone like you has gone through the same process of reasoning and come to a different conclusion, that fact just by itself is some evidence that you might be wrong. It may be very weak evidence, and you may not have to “adjust your credence” — i.e. become more or less confident — very much, but it is some evidence, and you should adjust your credence to some extent. (As I said, just how much is up for grabs)

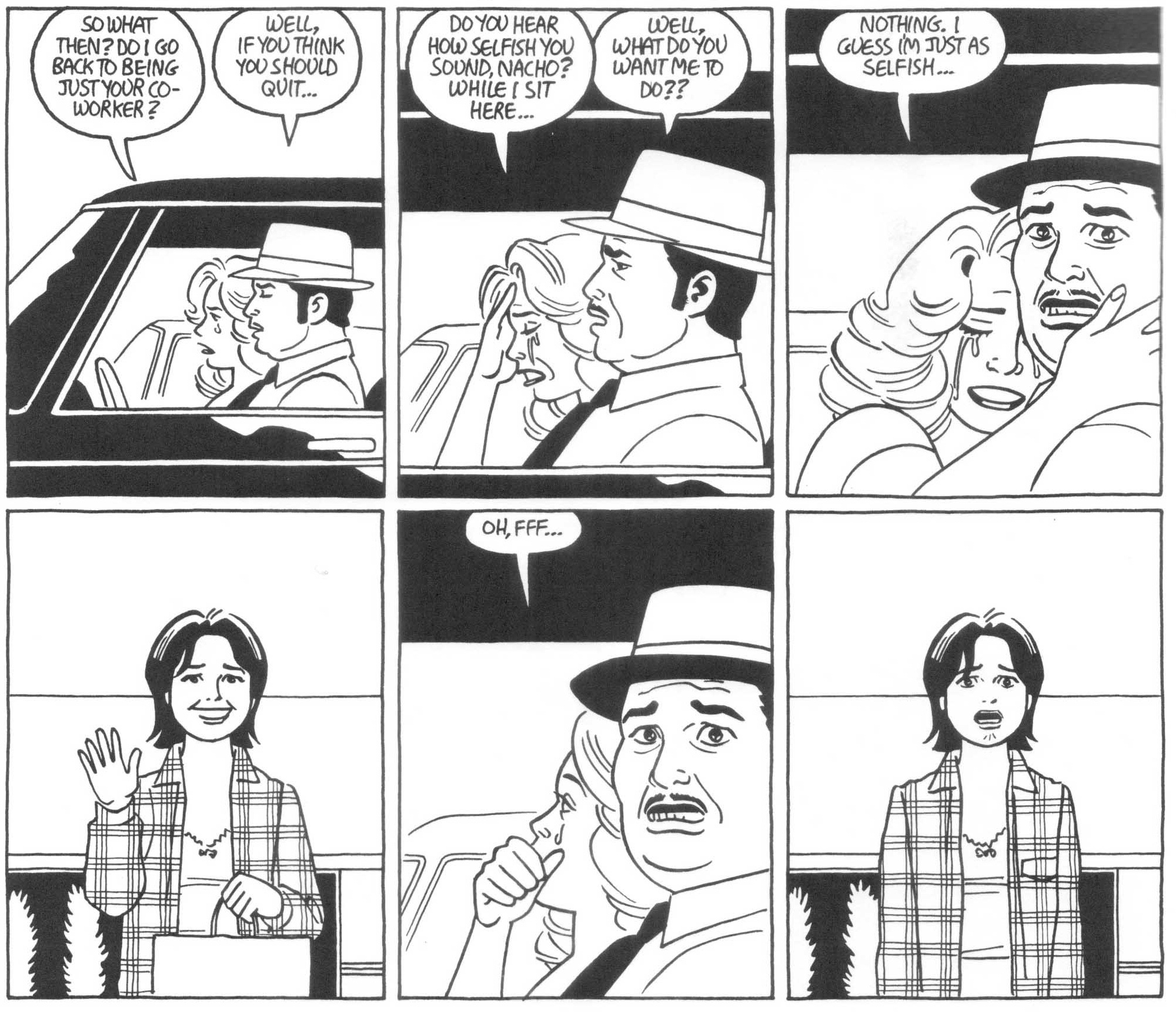

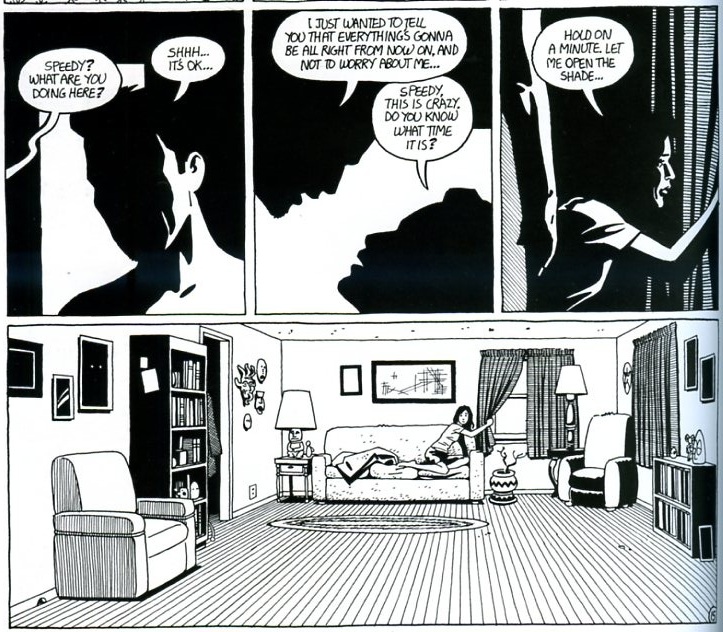

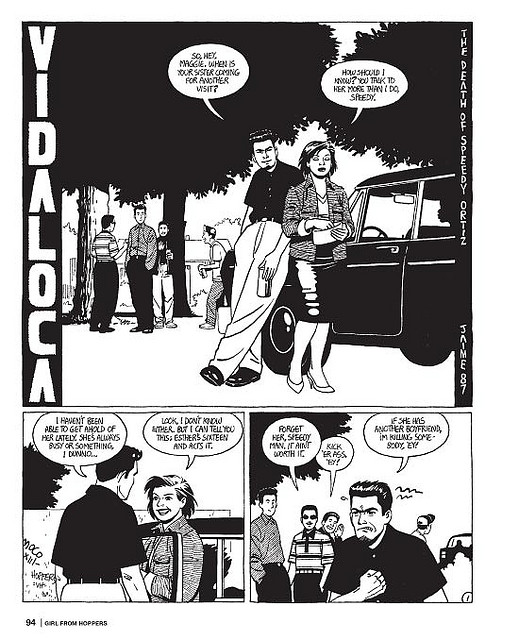

Here’s a hypothetical example: suppose Gilbert and Jaime are sitting at the table, trying to add up their joint profits from the most recent issue of Love and Rockets. (I told you we’d come back to comics)

Now, further suppose they go through their calculations separately, but using the same information and each using his own electronic calculator. And, finally, suppose that, at the end of all this, each brother arrives at a different total. Before they share their results with one another, each brother is fairly confident in his own calculation. But what happens when they share their results and realise that they disagree? According to the Correct View, each brother should become somewhat less confident in his own calculation.

And since, by definition, the Correct View is correct, this is just what they should do.

It’s important to remember that OTHER THINGS should be EQUAL when deciding how to react to disagreement. If Jaime knows that he is better at maths than Gilbert, then Jaime should not take Gilbert’s result as seriously, and hence should not reduce his own confidence as much (if at all); and vice versa. Similarly if Gilbert knows that Jaime’s calculator is broken; or Jaime knows that Gilbert forgot to count all the money; or Gilbert knows that Jaime wasn’t really paying attention; or…

The point being that you shouldn’t react to all disagreements in the same way. You should revise your confidence, down or up, only when you find that you disagree with someone who is in at least as good (roughly) an epistemic position as you — someone who is your epistemic peer. That’s why you don’t have to start believing that the end is nigh whenever you pass a religious fanatic on the street, or that global warming is a hoax when you watch Fox News, and so on — because these views arise from people in worse epistemic positions than you (or the proxies from whom you ultimately derive your opinions).

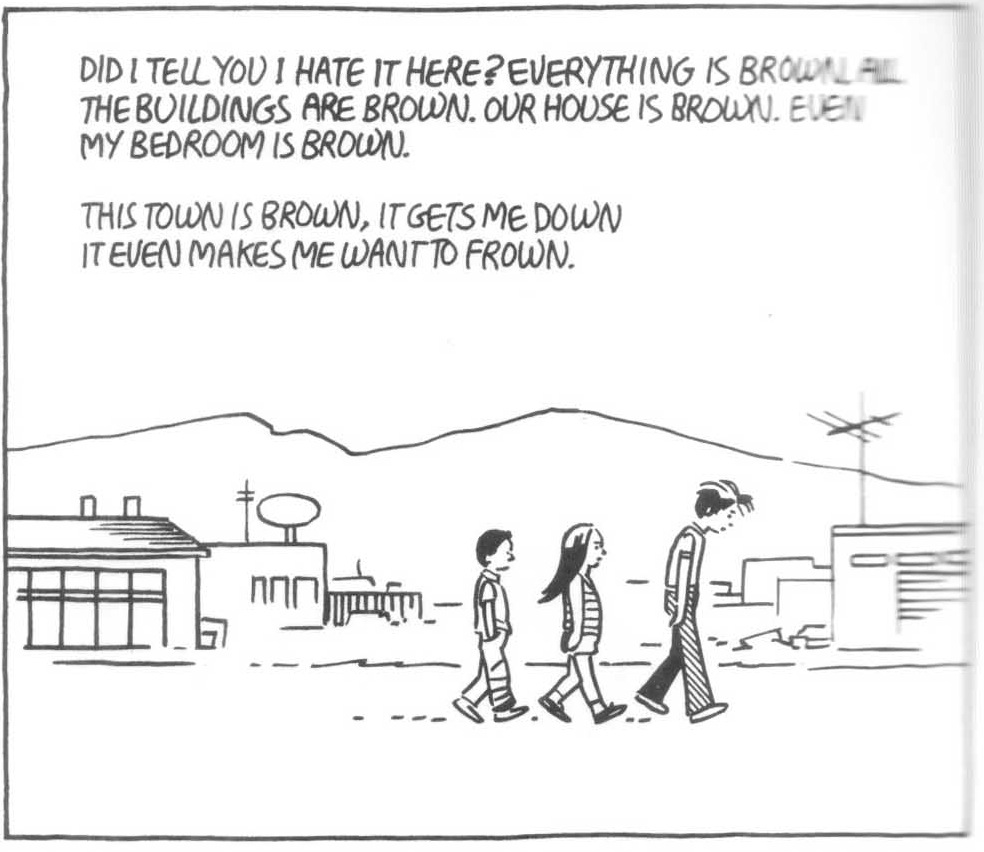

If you’ve followed me so far, you can probably see where this is going. As with opinions in general, I submit, so with opinions about art. In short: if you think a particular work of art is a piece of shit, but lots and lots of your epistemic peers think it’s the bees’ knees, you should seriously consider the possibility that you’re wrong. And maybe you should do this even if they can’t point to any convincing evidence in their favour.

Actually, this aesthetic conciliatory view follows from the Correct View only if we make a few extra assumptions. First, we have to assume that aesthetic sentences express propositions — or, to put it in English, that a sentence like “The Love Bunglers is one of the greatest comics of all time” is actually trying to describe how things are, rather than merely giving voice to your tastes. The former is like saying “I hurt my foot” or “I like ice cream”; the latter is like saying “Ow — my foot!” or “Ice cream — yum!” The former can be true or false, and even debated, but the latter cannot.

The second assumption is that the propositions expressed by aesthetic sentences are not entirely individualistic — that their truth does not depend solely on your reactions during the act of experiencing the art. If “The Love Bunglers is one of the greatest comics of all time” was merely a statement of how you felt about it, then, again, there’d be no room for disagreement. One person — let’s call him “Jeet” — could assert it, another — let’s call him “Noah” — deny it, and both could be speaking truly; just as one could truly say “I like ice cream” and the other “I don’t like ice cream”.

In other words, whatever makes some aesthetic opinions true and others false, it had better not be something that is entirely peculiar to whoever holds them.

Here’s one way aesthetic truth could depend on facts outside the individual: maybe the sentence “The Love Bunglers is one of the greatest comics of all time” is true only if The Love Bunglers properly reflects the Metaphysical Form of Beauty, which exists outside time and space, and doesn’t depend at all on what we humans think about beauty, trapped as we are in Plato’s cave.

Or, since that’s patently preposterous, maybe not.

Here’s a picture of aesthetic truth that is slightly more plausible. You have a set of preferences, values, likes and dislikes when it comes to art — let’s call them your tastes. Tastes are not permanently fixed, but they are usually stable over the short- to medium- term: if you like horror films today, then you’ll probably like them tomorrow. They can be very narrow or very broad: you might like films that are satires; and you might also like films that feature a combination of bicycles, conga lines, and references to Dante — in which case, have I got a film for you… And, crucially, although tastes vary from person to person, they are not entirely unique to each individual; you can share, to a greater or lesser extent, your preferences with other people. When you share your tastes with other people, we can say that you belong to an aesthetic community with those people; since you probably won’t share your tastes exactly with anyone else, you’re probably part of many different, partially overlapping communities.

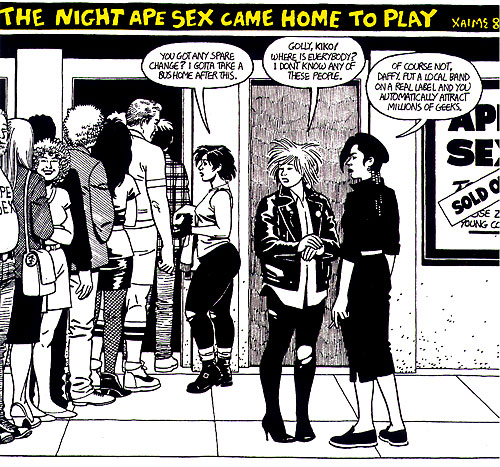

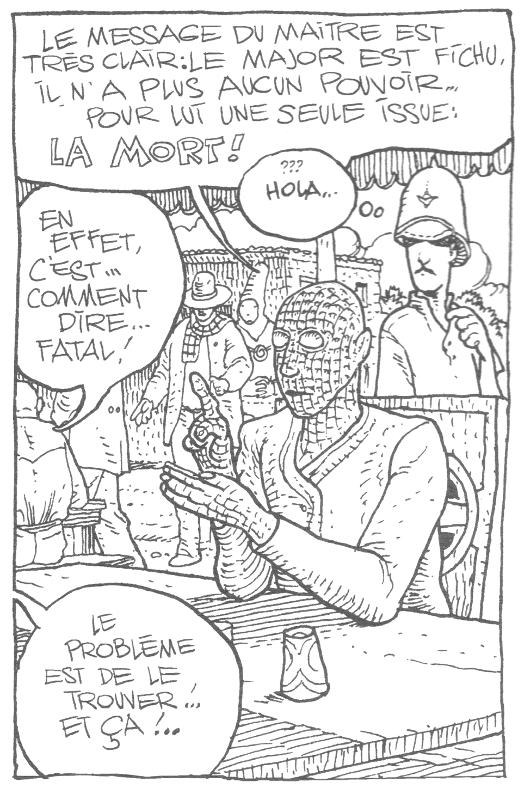

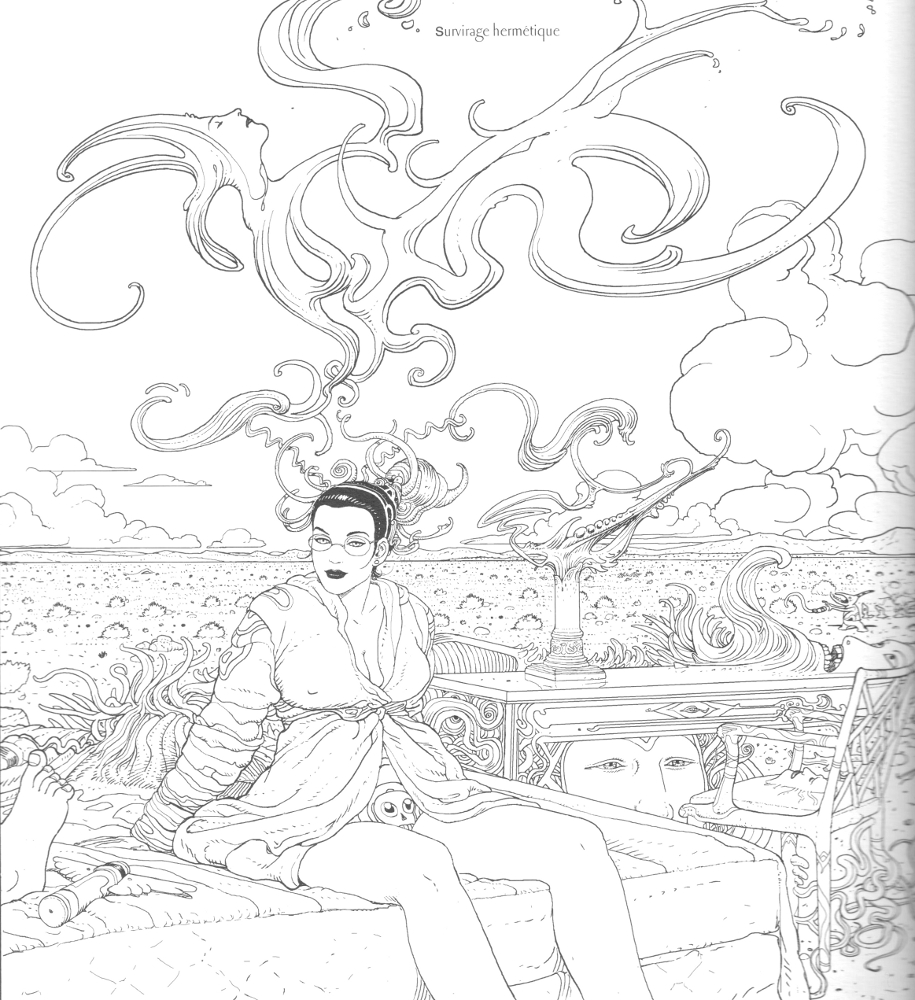

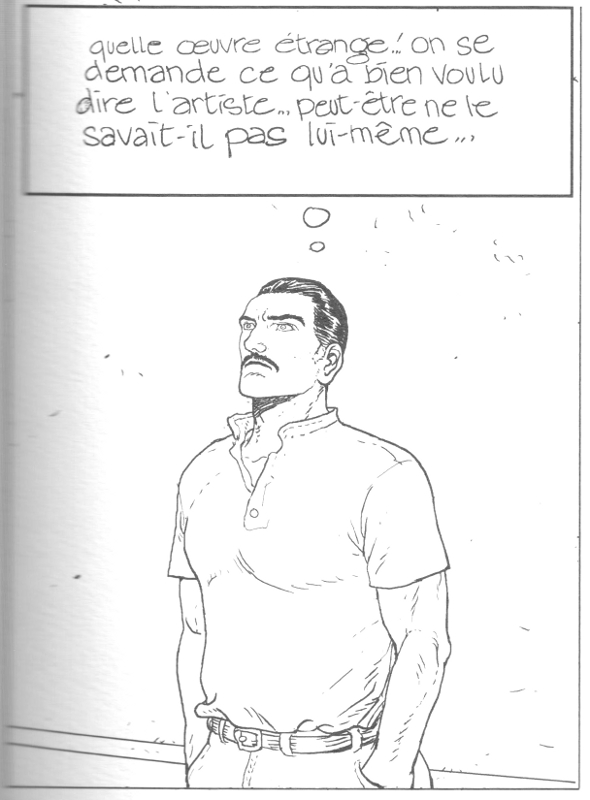

This, for instance, is considered a thing of great beauty in some communities:

Aesthetic claims, in this picture, are made true by (1) the properties of the artwork in question and (2) the appropriate aesthetic community. The community sets the standards for judging the artwork, and the artwork itself either meets or fails to meet those standards. Which community is appropriate depends, basically, on who is considering the claim. So, in some communities, the sentence “Alex Ross is a great cartoonist” is true; in others, it’s false.

When a critic makes an aesthetic claim, then, it doesn’t make sense to ask whether it is true-full-stop (“true-period” for our benighted Yankee cousins). What must be asked, rather, is whether it is true given the standards of the appropriate aesthetic community. The advantage of this picture is that aesthetic claims turn out to be relative, but not solipsistic; their truth can meaningfully be debated between members of any particular community.

So, let’s go back to the issue of disagreement, with these two assumptions granted, namely: (1) aesthetic sentences can be true or false; and (2) their truth or falsity depends on more than just individual taste. As we saw, how you respond to disagreement depends on whether your disagreer (so to speak) is your epistemic peer. How you respond to aesthetic disagreement further depends on whether your disagreer is your aesthetic peer.

That means that, when you’re confronted with aesthetic disagreement, you need to ask yourself two questions. First, is my disagreer in a better position than me to appreciate the artwork, a worse position, or a roughly similar one? If the answer is “worse”, then you can safely ignore them; alternatively, you can publicly call them out in a blog post.

What sort of thing would determine your relative position to judge the artwork? Any number of things, including (but not limited to): who’s more familiar with the artist’s other work; who’s more familiar with other examples of the same genre; who knows more about the particular techniques involved; who’s wasted more years on a fine arts major; who can cite more passages of Lacan; etc. etc.

Anyway, if you decide that your disagreer is at least no worse off than you from an epistemic perspective — in terms of knowledge, expertise, intelligence, etc. — you can then move to the second question, viz. Is my disagreer addressing what I think is the appropriate community? Naturally, the answer to this depends on what you think the appropriate community is — and, equally naturally, this is a vexed and contentious decision.

Many online folks who talk about comics restrict themselves (knowingly or not) to addressing a very small aesthetic community. And if you don’t care about that community, then you can just ignore their proclamations about, say, the greatest cartoonists of all time.

Breathe a sigh of relief — I just validated your life choices.

More interesting are cases where you and your disagreer see yourself as sharing membership in at least one community. That’s where disagreement bites – – you’re now disagreeing about how the artwork in question (say, “The Love Bunglers”) lives up to, or falls short, of your shared tastes. And you can point to this or that feature in support of your opinion.

But — and here’s where we draw it all back together — if the Correct View is correct —

and it is, by definition

— then you should consider changing your mind even without being shown the opposing “evidence”. Because the fact that a member of the relevant aesthetic community has had one reaction to an artwork, and formed a particular view about it, that fact itself is evidence that your own view is mistaken. It’s evidence that, in fact, the artwork has a different relation to the community’s standards than the one you think: that it’s the bee’s knees, rather than a piece of shit. Or the other way around.

So, in conclusion:

Jaime rules, just because we said so.

Also:

DON’T JUDGE MY LIFESTYLE

—————————————

The Locas Roundtable index is here.