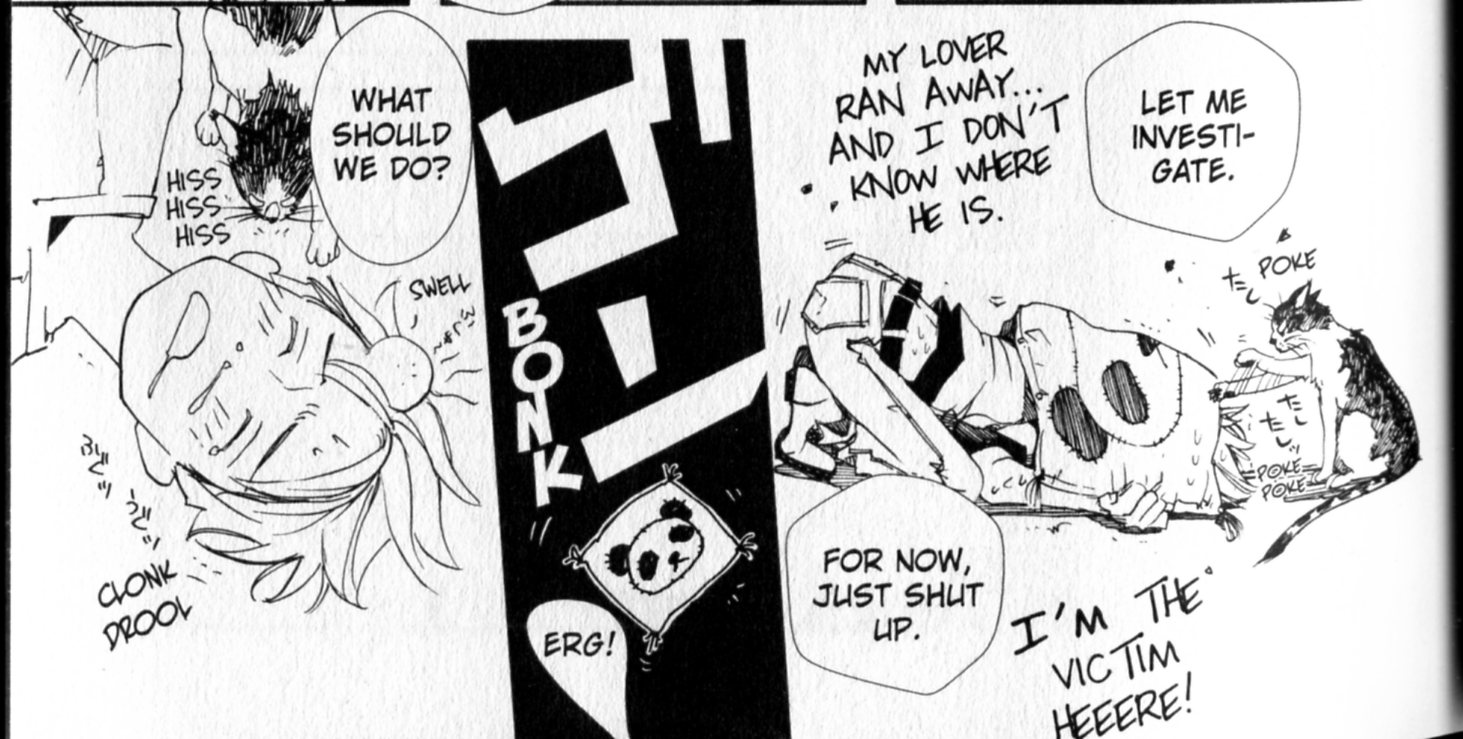

100 Scenes, a graphic novel by Tim Gaze

With Tim’s permission: to Antoni Tàpies in memoriam…

Comics writer and historian Alfredo Castelli said that, even if, for the best of his knowledge, the first newspaper Sunday Comic Section in the U.S.A. to regularly adopt the title “Comics” in short was published by the St Louis Globe Democrat in 1902, the word “comics” was well established to refer to the art form by the 1910s only. I don’t know who, at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century (I suppose) first applied the already existing word “comics” to fulfil this new function…

On the other hand German art historian Wilhelm Worringer used the already existing word “abstraction” to apply it to the visual arts in the title of his book Abstraktion und Einfühlung (Abstraction and Empathy), published in 1908. The concept predated the actual invention of abstract high art by some Russian painter (probably Wassily Kandinsky, but Mikhail Larionov is also a possibility – and how about Kasimir Malevich and Czech painter František Kupka?).

I’m saying the above because I joined the two concepts and coined the expression “abstract comics” (I wouldn’t be surprised if someone in the below comments proves me wrong though…). Andrei Molotiu reminisces:

I first began thinking of abstract comics as a concrete possibility during a discussion with Domingos Isabelinho on the TCJ board in the summer of 2002, on a thread with the rather awkward title, “Is there a Hemingway or Faulkner of comics?”– or something of the kind.

I don’t remember any of this to tell you the truth. In fact, I didn’t pay any attention to my “discovery” (so much so that I saved a few TCJ‘s messboard threads, but not this one). Abstract art was, to me, such a natural thing that I mentioned abstract comics without giving it a second thought. Here’s the only thing that I remember (or misremember, but I hope not…): at some point in the thread the two possible readings of a comics page came about. It’s possible that I mentioned French comics scholar Pierre-Fresnault Deruelle and “his” theory of the linear (a vectorial succession of panels – what I call “a reading”) and the tabular (the page as a random visual whole – what I call “roaming”). (I didn’t know it at the time, but said analysis is not by Deruelle who published it in 1976. Said theory’s author is Gérard Genette who published it in 1972 – he called the former a “successive or diachronic reading” and the latter a “global and synchronic look[.]”) to illustrate these two readings I posted the image below by Lettrist writer, filmmaker and draftsman, Isidore Isou:

Isidore Isou, 1964.

I said at the time that the page could be read/viewed in two ways: (1) as a drawing (the global look), (2) as an abstract comic (the successive reading). (I don’t remember my exact words back then, but I don’t want to imply now that the former isn’t part of a comics reading proper.) Anyway, this took too much space already and, in the doubtful chance that you, dear readers, are still interested, too much of your patience and time. Sorry for the self-indulgence!…

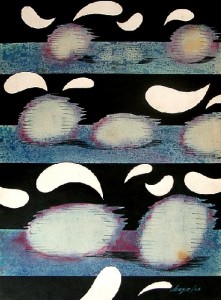

Contrariwise to what happened with Wilhelm Worringer the expression “abstract comics” didn’t predate abstract comics. Looking back we may found many examples in other fields. The one below is by Portuguese visual poet Abílio:

“Humor” by Abílio, 1972.

My favorite example comes from the comics field though. I mean the following example from Cuba:

The Amorphous and Disheartening of Vacuous Dialog by Chago Armada, 1968.

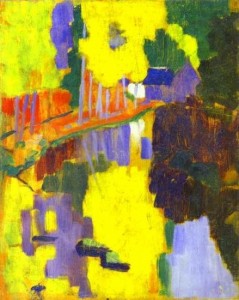

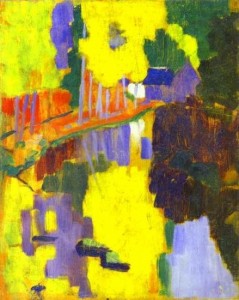

One of the roots of abstract art is Symbolism, the Gauguin inspired Nabis especially as we can see below:

The Talisman, the Aven River at the Bois d’Amour by Paul Sérusier, 1888.

It was fellow Sérusier Nabi painter Maurice Denis who said:

Remember that a painting, before being a battle horse, a nude woman or any anecdote, is essentially a plane surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.

Kandinsky’s abstract art was born in an atmosphere similar to the Pont Aven one, in Munich this time. I mean the Blaue Reiter (the blue rider) lyrical Expressionist group, of course. Around 1912, when his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art was published, Kandinsky was interested in Theosophy and Symbolism (he admired Belgian poet Maurice Maeterlinck). In fact, when he seemed to be occupied mainly by formal problems he stressed the importance of his work’s content (1925):

I would really like the spectators to go beyond the fact that I chose triangles and circles. I would like them to see what’s behind my paintings because that’s the only thing that interests me. I always viewed the problems of form as secondary… I know that the future belongs to abstract art and I’m dismayed when other abstract painters don’t go any further than form…

First Abstract Watercolor by Wassily Kandinsky, 1910.

Other wings of abstract art starting with Malevich and the Constructivists will be more formalist, but we’ll have to jump a few years in order to arrive at Tim Gaze’s book 100 Scenes, a graphic novel. Before leaving Kandinsky, for now, I want to stress what’s in common between the two: they both had/have an interest in music (in Tim’s case it’s Dubstep). Following Lithuanian painter and musician Mikalojus Ciurlionis Kandinsky believed in a synesthetic relation between colors and sounds (1912):

Yellow is disquieting to the spectator, pricking him, revealing the nature of the power expressed in this color, which has an effect on our sensibilities at once impudent and importunate. This property of yellow affects us like the shrill sound of a trumpet played louder and louder, or the sound of a high pitched fanfare. Black has an inner sound of an eternal silence without future, without hope. Black is externally the most toneless color, against which all other colors sound stronger and more precise.

It’s easy to know where Tim Gaze is coming from because he tells us so in his Notes. He cites three main references: Andrei Molotiu’s abstract comics and “ground-breaking volume Abstract Comics: The Anthology (2009)[;]” Surrealist art and techniques (collage books and decalcomania paintings by Max Ernst); Henri Michaux’s Tachiste (Pierre Guéguen, 1954) sequential work. One may say that, briefly, Surrealists and Tachists (Informal Art, Art Autre – Art of Another Kind -, as Michel Tapié put it in 1951, 52) advocated a spontaneous, irrational, kind of art. Both groups were fascinated by drug use, magic, popular art and, sorry for using an expression that I don’t like much, outsider art (Jean Dubuffet’s Art Brut)… Informal artists are the European equivalent of the Abstract Expressionists in the U.S.A..

100 Scenes, A graphic Novel by Tim Gaze, 2010.

Tim Gaze says that his graphic novel “touches upon two emerging areas: abstract comics […] and asemic writing.” I’m with Kandinsky when he said that “[t]here is no form, there is nothing in the world which says nothing.” Writing may be asemic as writing, but a sign is a visual entity signifying with visual means (as Tim put it: “[t]hese areas transcend languages, and offer the possibility of inter-cultural communication without words.” (Just like music, right?…) As Tim puts it, polysemy is high in his book:

This is an open novel, for you to project your mind into.

Every page is a stimulating field for your imagination.

So, there’s no predetermined meaning here, entropy is at its fullest, we have achieved maximum energy.

We may start with the cover of 100 Scenes above. I asked Tim if the book had anything to do with Katshushika Hokusai’s One hundred views of Mt. Fuji. He answered me that “only the title has any connotation of Hokusai.” So, false clue there, I would say… First of all: is this a novel as the cover claims? How can it be if there are no characters or plot? Isn’t the concept of “graphic novel” stretched to the breaking point? I would answer yes to the first question and no to the last one. We don’t even need to go further than the cover to understand these answers. There are at least two reasons to explain them:

(1) The cover of a book is what Kandinsky called, the basic plan. Without the title (without the words) the basic plan would be a square (as we can see above). So, it’s the book’s format that limits the basic plans’ choice.

(2) A drawing on a gallery wall (or a comics original panel) has a materiality (white pentimenti, irregular intensities of black, the paper texture, etc…) lacking here. What we have above is an image of an image of an image (a copy of a monoprint): i. e.: in McLuhan’s terms the hot drawing cooled down creating a distance that, in Benjaminian terms, provoked the loss of its aura. Hence: there’s a movement from the visual arts to literature: the graphic novel…

Having established that we may now answer the second question: the comics people co-opted the word “novel,” but graphic novels have their own specificity being nothing like novels.

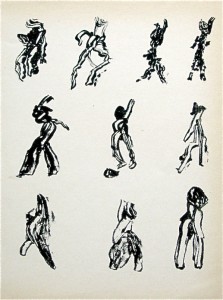

The drawings in 100 Scenes result from various tensions, then (to use another Kandinskyan word): human made / machine reproduced; line / texture; black / white; positive space / negative space; centered / decentered; stillness (the basic plane) / movement (the drawings); chaos / order; regular rhythms / irregular shapes; etc… From page to page we witness a restless, lively world. It’s like a godless theogony (another tension?) in which trial and error coexist. I’m on the verge of denying the abstract nature of this graphic novel, so, I’ll stop now…

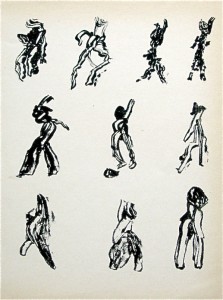

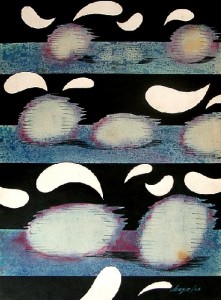

Page from 100 Scenes: the regular rhythm, the irregular shapes, in ascension.

I’ll finish with part of Henri Michaux’s postface to Movements, 1951:

Whoever, having perused my signs, is led by my example to create signs himself according to his being and his needs will, unless I am very much mistaken, discover a source of exhilaration, a release such as he has never known, a disencrustation, a new life open to him, a writing unhoped for, affording relief, in which he will be able at last to express himself far from words, words, the words of others.

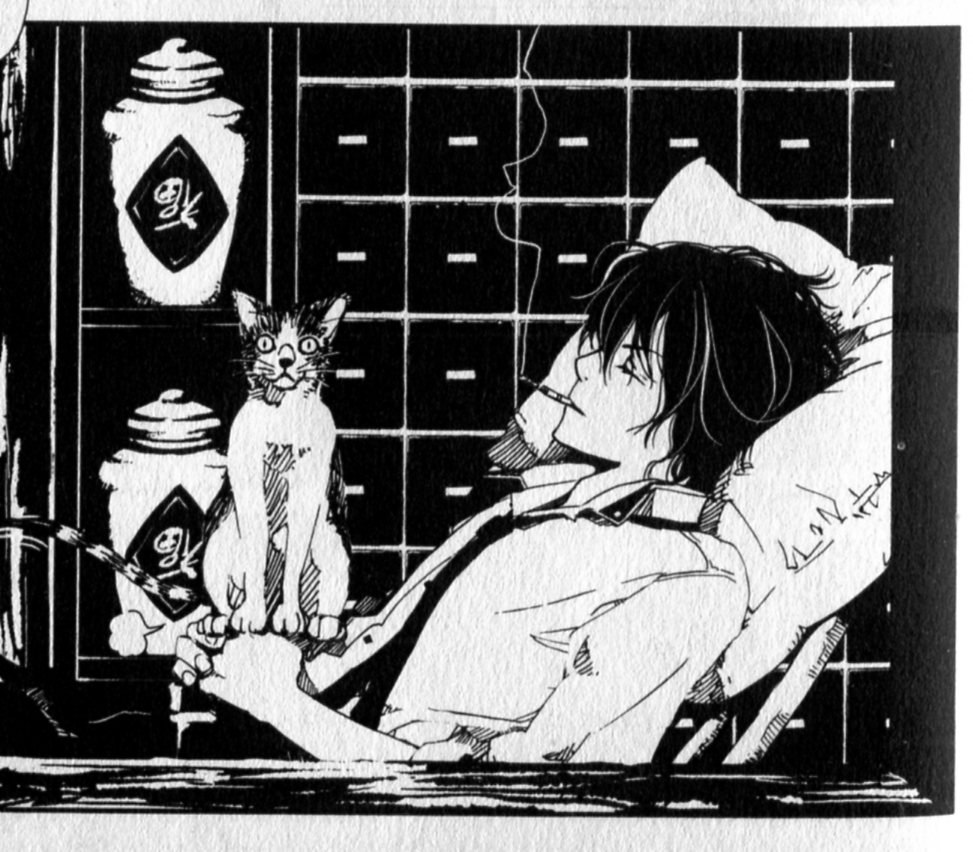

Page from Movements by Henri Michaux, 1951.