Recently, as part of an interview with Kevin Smith, Grant Morrison claimed that all these years no one has gotten the ending of Alan Moore and and Brian Bolland’s The Killing Joke (1988). Morrison claims that those obscured and silent final three panels are meant to suggest that Batman is finally killing the Joker—breaking his neck or strangling him. In other words, The Killing Joke is a form of final Batman story. In the interview Kevin Smith reacts to this interpretation as if it were some form of big revelation that utterly changes the framework for understanding the story. The reaction on the web was mostly similar, just look here and here and here. Comment threads on stories reporting this were filled with a lot of speculation about how this killing interpretation holds up in light of the fact that some of the events from The Killing Joke (like the crippling of Barbara Gordon) made their way into the main Batman continuity, because clearly the Joker is not dead.

I think it an adequate, but nevertheless anemic interpretation. Sure, the killing exists as a possibility, but other and more sweetly radical possibilities might actually redeem (in part) a great, but flawed book, that Moore himself later repudiated. The Killing Joke is built on the uncertainty inherent to the serialized superhero comic book medium, so we can’t look to what was included or not included from it in the main continuity as evidence of the acceptability of Morrison’s interpretation, because the book itself works to remind us of how the history constructed by long-running serialized properties are incoherent. No. I think the interpretation’s weakness comes from being an unimaginative ending to the Batman story. The Killing Joke reminds us that as a series of events the Batman story makes no sense, but rather it coheres through the recurring structural variations within that history. Moore is having Batman and Joker address that structure in a winking and self-referential way. Violence, even killing, is already a central part of the recurring interactions of these characters (how many times has the Joker appeared to die only to return?), so why give weight to an interpretation claimed as an end that only gives us more of what already explicitly pervades the entire genre—violence? Instead, a close “listening” to how Moore and Bolland use sound (particularly, the lack of it in certain key panels) to highlight the queerness of the Batman/Joker relationship provides the reader with a different way to interpret those final panels.

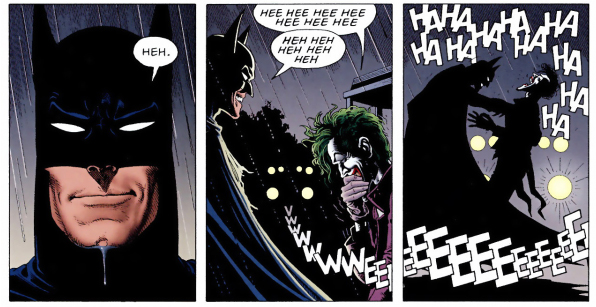

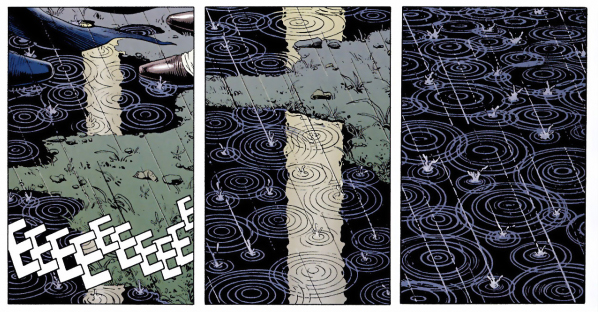

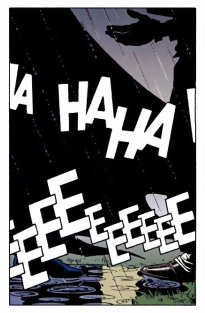

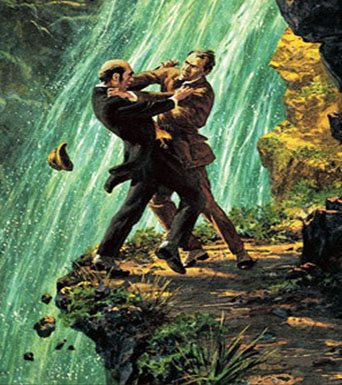

I contend that rather than indicating violence, that final silence is recapitulating an intimacy between the Caped Crusader and the Clown Prince of Crime that is found in several silent panels throughout the work and that echoes the intimacy implicit in the structure of the Batman/Joker relationship. As such, in the end, when the Joker tells the joke that makes Batman join in the laughter, when the Batman grabs the Joker by the shoulders and the panels shift their perspective to show the Joker’s hand kind of reaching out towards Batman’s cape amid the depiction of their laughter and the approaching sirens, followed by a panel that shows only their feet (and a wisp of Batman’s cape), and then finally just silence amid raindrops making circles in a dirty street, instead of violence, I imagine they are locked in a passionate embrace and kiss.

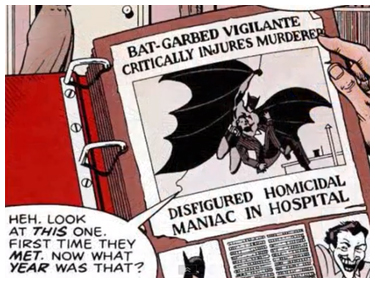

In his book, How to Read Superhero Comics and Why, Geoff Klock does a great job of breaking down how The Killing Joke is structured in a such a way to comment on the contradictions, misprision and re-imaginings that pervade the histories of these characters. While Moore’s comic plays on the idea of the Joker and Batman being two-sides of the same coin—two men playing out their psychotic breaks in different (but dangerously violent) ways after experiencing “one bad day”—the profound similarity between the two is one that emerges from the structures of the serialized medium they appear in (and in the multiple mediums versions of these characters have appeared in over the years). They both have deeply entwined “multiple choice pasts” that outside of their individual encounters of repeated conflict makes for a farraginous and incoherent history. It is the structure of the relationship and the homosocial desire it represents that provides a foundation for understanding their stories regardless of the confusion of how long it has really been going on and what from it may or may not really “count.”

The Killing Joke is an even more brutal and direct indictment of the superhero genre’s state of arrested development than Watchmen (1987) was. Moore’s work seems to want to drain any remaining appeal from their accreted and subsequently problematic histories by appearing to complete the trajectory that Batman expresses concern about in the text itself. Unfortunately for Moore, however, it didn’t quite work. A work built on highlighting the artifice of the comic pastiche becomes something of a lauded lurid spectacle. Even though The Killing Joke seems to consciously want to stand outside of continuity it nevertheless falls victim to continuities’ power to assimilate or exclude narrative events. Thus, the maiming of Barbara Gordon and the suggestion that she’s raped were later rehabilitated into the main continuity of the Batman line (wheelchair-bound, she becomes the superhero dispatcher, archivist and IT-tech, Oracle). So, in the same vein it is not outside the realm of possibility that Grant Morrison could be right and the death of the Joker has simple been excluded from continuity in the same way that “official” history ignores Bat-Mite or the Rainbow-colored Batman costume. However, within the skein of The Killing Joke itself, the possibility of a kiss, of a breaching of the limits of their homosocial bonds to transform it into a homosexual one not only fits within the structure of their relationship, but levels a more powerful indictment against the pathologies of repression and violence that pervade the genre.

Batman killing the Joker may be a suddenly popular interpretation of the end of The Killing Joke because many readers seem uncomfortable with the unresolved ending of the two of them standing in the rain laughing until their laughter fades away under the howl of an approaching siren and then becomes silence. For some, for Batman to laugh along with Joker is too “out-of-character” and/or shows that the Joker is right all along—the world is an unjust and disordered place and for Batman to think he can provide order by dressing up as a bat and beating people up is as crazy as running around performing random and outlandish acts of violence as a way to get a laugh. But I see that shared laughter as indicative of not only an unresolved narrative tension, but also sexual tension. It is a “here-we-are-again-drawn-together-but-at-an-impasse” kind of laugh (which is an echo of the joke itself). Sure, the idea that Batman and Robin had/are having some kind of sexual relationship has long existed, but there is a kind of rough intimacy to the Joker and Batman relationship that makes me agree with Frank Miller that their relationship is “a homophobic nightmare.” Joker can be seen to represent what happens when you allow queerness free reign, Batman when it is closeted. They are both extreme reactions to a comic book world where queerness is defined as deviancy, and as such deviant behavior is the only way to express the queerness underlying their relationship. Any chance to express intimacy outside of those confines is engulfed in silence, and it is by seeking out these silences in the text (or how sound and silence interact) that this special bond between them is demarcated.

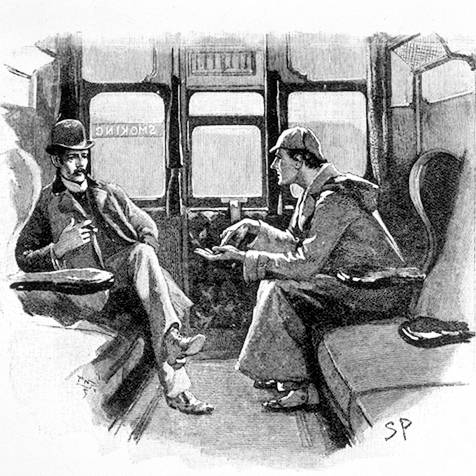

The book opens with three straight pages (22 panels) without a word of dialog and no narration. Instead we have the typical establishing shots that perfectly capture the prison for the insane/sanitarium trope used whenever the Arkham Asylum set piece appears. Batman is not here to solve a mystery or quell a riot. He arrives to pay a personal visit to the Joker. When the silence is finally broken, Batman speaks. “Hello. I came to talk.” This is a profound reversal. The panels here alternate between a normally taciturn Batman doing all the talking—expressing his feelings, seeming almost desperate in his desire to reach the Joker—and the normally boisterous talkative Joker being silent. The scene is punctuated by the the “FNAP” of the Joker putting down cards in a game of solitaire. The scene has the rhythm of a tense discussion regarding a topic long in the air, but only finally broached by an anxious or disillusioned lover. There is a desperation and emotionalism that seems to emerge from long contemplation on the part of Batman about his relationship to the Joker. The visit suggests that Batman has come to accept that violence will not resolve the conflict between their extreme reactions to a queer identity. When the man in the cell turns out not to be the Joker at all, but a double duped into taking his place while the real Joker escapes, that moment melts back into something like the “typical” Batman and Joker story. Joker has escaped and needs to be captured before he accomplishes some outlandish and murderous scheme.

This time, the Joker’s outlandish plan involves driving Commissioner Gordon mad as a way to get Batman to admit their similarity through madness. The image of the Commissioner stripped naked and made to wear a studded leather bondage collar does a lot to equate madness and queerness run rampant. The Joker’s desire for Batman to “come out” and admit they are the same echoes a dichotomy between the closeted and the “out” individual. The Batman character is largely about his secret identity, the construction of a hyper-hetero playboy cover for his life in spandex and a mask, tackling, wrestling and binding (mostly) other men in the guise of combating criminal deviance. He is homophobia turned inward. The Joker on the other hand has no identity outside of being the Joker. He embraces his mad flamboyance and doesn’t see it as deviant, but as a different form of knowledge about a world that could create him and/or Batman. The Joker is dangerously queer and that is his allure. He is the manifestation of licentiousness that homophobia conjures when it imagines queerness.

Even the past given to the Joker in The Killing Joke reinforces this idea. Sure, he is given a pregnant wife in the version depicted, but her death frees him from the yoke of a heteronormative life as much as being chased into a chemical vat by Batman does. It is suggested that losing his wife is just as much to blame for Joker’s particular madness, but the real clincher is Joker’s assertion regarding his past: “Sometimes I remember it one way, sometimes another… If I’m going to have a past, I prefer it to be multiple choice!” Despite the choice between these varied pasts, what remains constant is the centrality of Batman to the Joker becoming who he is, which helps to fuel the Joker’s desire to have their relationship be of primary importance in Batman’s life (as it is in his). Whatever violence the Joker commits, whatever other desires he may evince, they are subsumed in that primary desire. In a genre where beginnings and endings are written, erased and rewritten so as to become a palimpest, it is the recurring structure of the characters’ engagements that define them more than any sense of origin or goal.

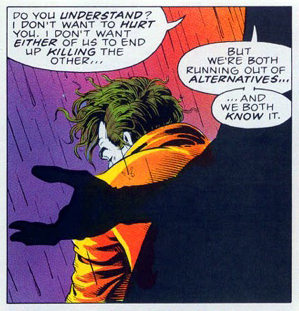

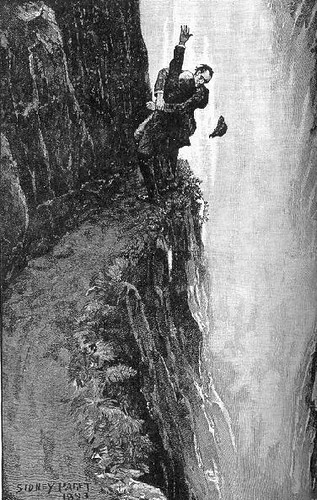

This intimacy explains the uncharacteristically intense tenderness with which Batman seeks to confront the Joker. When he catches the Joker near the story’s end, Batman finally gets to broach the subject, to bring up the issue that precipitated his attempted visit with the Joker earlier. He says, “Do you understand? I don’t want to hurt you,” and makes the offer: “We could work together. I could rehabilitate you. You needn’t be out there on the edge anymore. You needn’t be alone.”

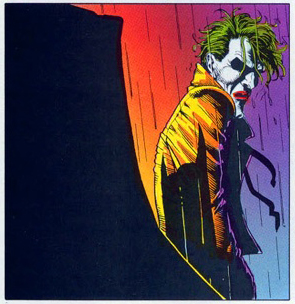

Look at the panel right after Batman makes that offer. There is a vulnerability to how the Joker is depicted. He is slightly hunched as if suddenly aware of the cold rain, his eyes are in shadow as if to hide tears and he is looking at Bats from over his shoulder with a frown that is at odds with his usual exaggerated grin. It is perhaps one of the few (if not only) human moments between these two characters and it is a silence.

The strange thing about Batman’s offer that the Joker contemplates in heavy silence is that “out there on the edge” exactly where Batman lives as well. The offer to rehabilitate the Joker is also an offer to rehabilitate himself—to rid them both of the desires that repeatedly and destructively bring them together. This is Batman as Brokeback Mountain. By making this speech, Batman is revealing himself to be something of a hypocrite, unless he means to find someway to admit his own flaws and overcome his own secrets, to really become a part of the “togetherness” that he suggests can help the two of them to avert their fate. The Joker refuses, saying “it is too late for that. . . far too late.”

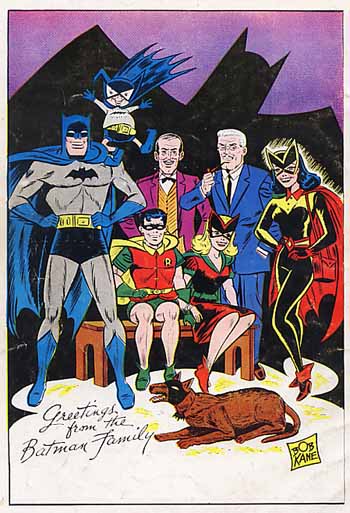

Silence marks several other important panels throughout the work, including Batman’s wistful look at the portrait of the anachronistic “Bat-Family.” The picture (made to emulate a Bob Kane sketch) depicts characters that no longer existed in the main continuity at that time. The original Batwoman and Bat-Girl (not Barbara Gordon) were editor-mandated creations—romantic interests for Bruce and Dick in order to combat the accusation of Frederic Wertham that Batman and Robin are a “wish dream of two homosexuals living together.” The inclusion of the portrait serves to destabilize the notion of coherent history that the whole of The Killing Joke is working at. But it is also a signal of the need in the past for Batman to have a “beard” written into the story to deflect gay accusations. It is a reminder that even the lighthearted era of the (now false) Bat-Family was part of a structure of secrets and lies meant to cover for fear of a repressed desire. The nostalgia of this scene is laid with irony, since the call to a simplistic normative family is belied by the constructed nature of that “family” and the queerness of their life of masks and costumes.

Even the most contentious scene in the graphic novel, the brutal shooting of Barbara Gordon, leading to her disrobing, (likely) rape and photographing, is attended to in silence. Now, I think the scene itself is part of what makes The Killing Joke flawed. Its brutal treatment of a beloved female character, who has been shown on more than one occasion to be able to hold her own, is egregious. The sexualization of the violence against her also serves to give the scene just the kind of morbid appeal that plagues a lot of contemporary comics, and distracts from the ways The Killing Joke can be seen as a (re)visionary text. It is completely unnecessary for Moore to make his point. Yet, regardless of its failure, the scene’s silence casts it as part of that unspoken attraction between Batman and the Joker. Like an especially twisted reference to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Between Men (1985), this is a love triangle, with Barbara playing the proxy for the desire between the “rival suitors.” Sedgwick writes, “in any male-dominated society, there is a special relationship between male homosocial (including homosexual) desire and the structures maintaining and transmitting patriarchal power. . . this special relationship may take the form of ideological homophobia, ideological homosexuality, or some highly conflicted but intensively structured combination of the two” (25). Thus, the maiming and violating of Barbara Gordon is not about her at all, but about the Joker’s desire for Batman. She is the proxy through which this desire is expressed as it literally serves to summon Batman to attend to him so they may take up their “highly conflicted, but intensively structured” relationship. It is this very structure that helps the Batman oeuvre to cohere despite its historical ambiguity.

The silence of those two final panels echoes the silence immediately following Batman’s offer, just as it parallels the silence that attends many of the scenes that highlight their intimacy. The silence is a recapitulation of that moment of tender vulnerability seen in the Joker as he contemplates the offer, and I think that silence is best filled not with violence —violence is loud and obvious and strewn throughout The Killing Joke and the entirety of the Batman canon—but rather with tender love. The silence is the signal for that which cannot be depicted or spoken aloud. It is an actual act of bravery on the part of Batman, proving to Joker that it is not yet “too late.” The Killing Joke’s abundant self-awareness regarding the incoherence of comic history also suggests an incoherent future where anything is possible as long as it can be enclosed in the broad structures of their relation—even Batman and the Joker as lovers. That—not violence, not a killing—would be an end to the Batman story as we know it.

I don’t see the kiss as the definitive action of those panels—I can’t say what really happens in because there is no “really happened”—but find it much more profound than killing. The kiss is a more delightfully radical possibility than the usual violence of the genre. It upends their entire history, but somehow still fits within its skein. The off-panel action remains unseen because that’d be a real end. Violence doesn’t change anything in superhero comics, it is a normalizing force that builds routine, and killing is just the beginning of a come-back story. It is love that transforms. Sure, it would be best if superheroes could move beyond the pathologizing of queerness, but to even have a chance to imagine a world where Batman and the Joker could both be saved from their violent self-destructive spiral through loving each other is too wonderful to dismiss.

________

Osvaldo Oyola is a native Brooklynite. As a kid in the early 80s, in the days before people got the idea that they might be worth something, he would scour flea markets and yard sales for cheap old comics from the 60s and 70s. These days he’s still obsessed with Bronze Age comics, but mostly for how they represent race, gender, and urban spaces. He is currently completing a doctoral dissertation on the intersection of pop culture and ethnic identity in contemporary transnational American literature, writing on Los Bros Hernandez, Junot Diaz and Jonathan Lethem. He still lives in Brooklyn, with his poet wife and cats named for Katie and Francie Nolan from A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. He writes briefish thoughts on comics, music and race on his blog, The Middle Spaces.