Art by John Romita,Sr, and Mike Esposito

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.– Paul the Apostle,1 Corinthians 13:11

Over the past seven chapters of this series, we have traced the evolution of the superman from the eighteenth century up to 1938 and the coming of the Superman comic book character: our history stops there, as the comic book medium was soon awash with superheroes, and would remain so until the present day.

Indeed, it is depressing to note, the commercial comic book is overwhelmingly dominated by the superhero at the expense of other popular genres. And the comic book superhero is at present – by consensus of its aficionados – in a state of decadence.

We’ve seen , with the death of the dime novel, of the newspaper serial and of the pulp magazine, how entire pop media can shrivel away. The comic book magazine may be fated to join these dinosaurs in extinction.

If it is, I doubt it will take the superhero with it. Hollywood and the electronic game have claimed this king of the four-color pamphlets. As pointed out in previous chapters, the superhero existed before the comic book, and will continue to exist after. It is a kind of contemporary archetype that resonates with twenty-first-century psyches, not necessarily in a laudable way.

The superhero is a vehicle for power fantasies. That is far from news, of course. And there are other character types that also cater to the reader’s craving for wish fulfilment; tales of business tycoons, brilliant inventors, heroic revolutionaries, boy wizards, femmes fatales, genius detectives, and ugly-ducklings-turned-superstars abound. But the superhero strikes one as being uniquely unhealthy due to the nature of its particular power dream.

When I was a small child — say around eight years old — my favorite superhero was Superboy. Part of his charm lay in the simple pleasure of identification with this kid (like me!) with wonderful powers — a not unwholesome fantasy.

However, consider the cover picture below:

Art by Curt Swan and George Klein

What does this image tell me about my childhood proxy? He’s alone, unjustly reviled by society (his own parents turn on him), despite his clear superiority to the rabble. Now, the illustration is obviously an exaggeration made to serve one transient story — but it’s the kind of exaggeration that would resonate with a child.

Powerless and dependent, a child craves nothing so much as agency and autonomy. His world is entirely out of his control; he is told to clean his room, finish his homework, stop talking back. Ah, but little do they know of his secret life as a superhero!

The superhero is thus an expression of resentment that the child co-opts. Other negative sentiments it expresses include anger, acted out vicariously by the systematic use of violence to solve all problems.

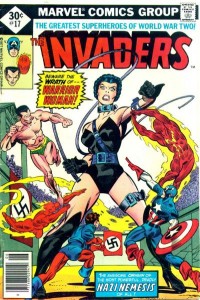

These ‘bad’ feelings, though, can of course serve to empower a child psychologically. I’m more worried at the persistence of superhero fantasies in the adult. Fictional superman revenge fantasies, as Gramsci pointed out, were one of the roots from which Fascism grew.

Most children tell themselves stories in which they figure as powerful figures, enjoying the pleasures not only of the adult world as they conceive it but of a world of wonders unlike dull reality. Although this sort of Mittyesque daydreaming is supposed to cease in maturity, I suggest that more adults than we suspect are bemusingly wandering about with a full Technicolor extravaganza going on in their heads. […]Though from what we can gather about these imaginary worlds, they tend to be more Adlerian than Freudian: the motor power is the desire not for sex (other briefer fantasies take care of that) but for power, for the ability to dominate one’s environment through physical strength […]

Gore Vidal, The Waking Dream:Tarzan Revisited

I’m not necessarily referring to adult comic book fans, either; the enormous success of various superhero movies shows that this figure resonates strongly with the public at large.

No, I doubt that the continuing allure of the superhero will lead to more vigilante ‘justice’, or to a resurgent Fascism. But it is time for one adult reader and comics lover to say goodbye: me.

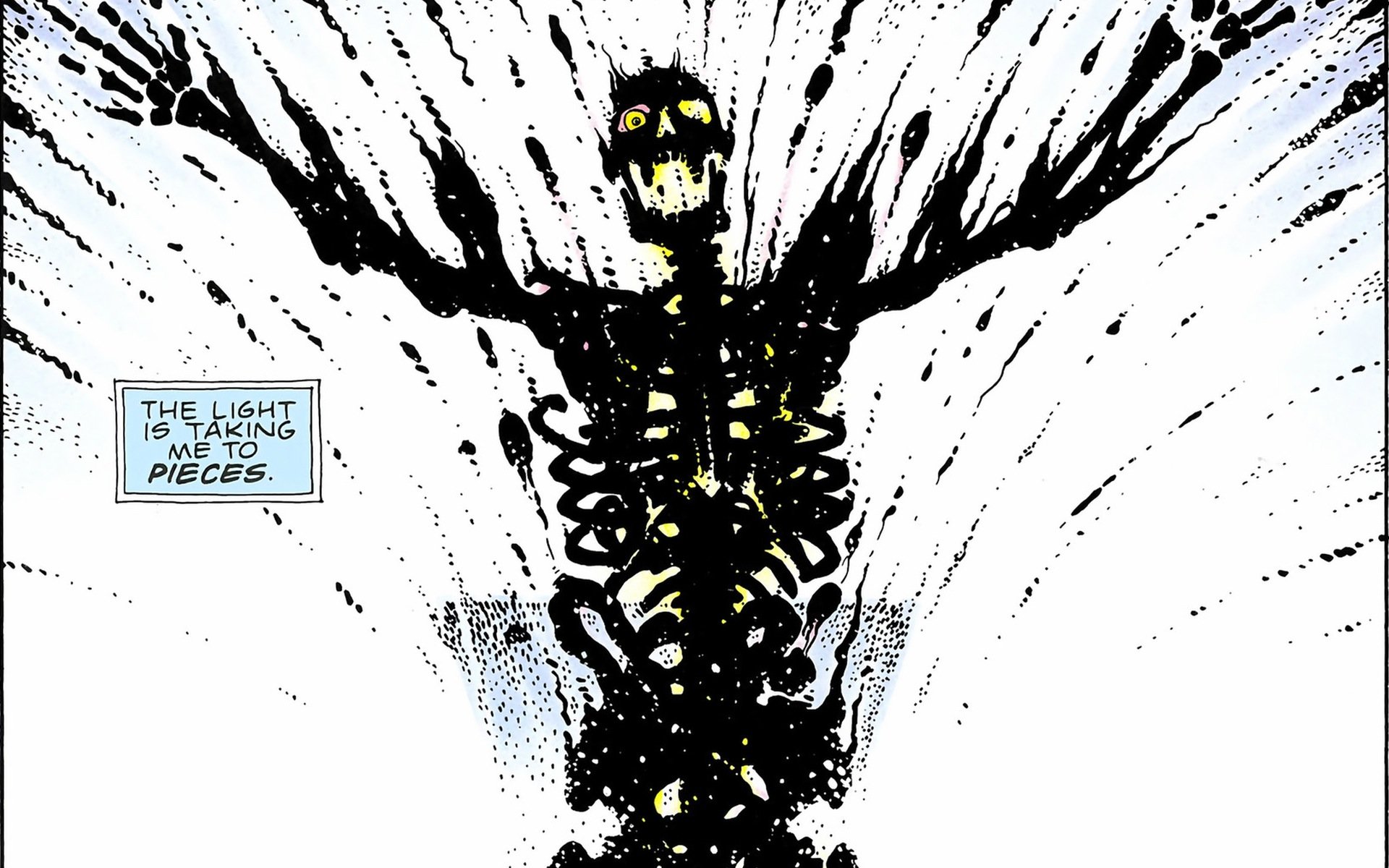

Art by Neal Adams. An even more self-pitying version…

* *

As for the superman, he has in recent years taken a new guise, in the movement popularly called transhumanism.

Transhumans — also called post-humans– are postulated future beings of human origin “whose basic capacities so radically exceed those of present humans as to be no longer unambiguously human by our current standards”, according to the World Transhumanist Association. The latter also defines transhumanism thus:

- The intellectual and cultural movement that affirms the possibility and desirability of fundamentally improving the human condition through applied reason, especially by developing and making widely available technologies to eliminate aging and to greatly enhance human intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities.

- The study of the ramifications, promises, and potential dangers of technologies that will enable us to overcome fundamental human limitations, and the related study of the ethical matters involved in developing and using such technologies.

Transhumanists foresee humans benefiting from radically extended lifespans (possibly even immortality), direct mind-machine interfaces, astonishingly high intelligence, perfect control of body processes…an entire laundry list of (so far) wishful thinking.

From the transhumanist site euvolution

Eventually transhumanity — whether the whole of the human race uplifted, or a tiny elite — may, in this scenario, slip the contingencies of existence and attain godhood.

One Christian author had foreseen such Luciferian hubris, and named it that hideous strength, in the book of the same title:

The time was ripe. From the point of view which is accepted in Hell, the whole history of our Earth had led up to this moment. There was now at last a real chance for fallen Man to shake off that limitation of his powers which mercy had imposed upon him as a protection from the full results of his fall. If this succeeded, Hell would be at last incarnate. Bad men, while still in the body, still crawling on this little globe, would enter that state which, heretofore, they had entered only after death, would have the diuturnity and power of evil spirits. Nature, all over the globe […] would become their slave; and of that dominion no end, before the end of time itself, could be certainly foreseen.

C.S.Lewis, That Hideous Strength (1945)

While the memory of last century’s racial atrocities endures, let us not be too quick to abandon mere humanity.

Resist the temptation of the superman.