Figure 1:Suicide Squad from the CW’s Arrow

The superhero has emerged as the trending symbol of our mediated world. Musings over Marvel’s and DC Comics’ relative successes adapting characters to the big and small screen opens the door to some interesting moments of cultural contemplation. As Peter Coogan suggests in a recent essay entitled, “The Hero Defines the Genre, the Genre Define the Hero,” the link between the superhero and the genre are not incidental.[1] The selfless nature of the superhero and its genre reflect pro-social values Americans feared threaten by a rising urban industrial order. Changing the superhero then, echoes wider fears of disruption stemming from the loss of tradition. In this framework, the superhero becomes a measure of communal stability in some minds. As the superhero evolves enough to maintain its relevance, these characters offer context for cherished values placed in a modern world. As these characters are recreated for film and television audiences, they provide a window on the pace and scope of our collective evolution.

Over the last two seasons, the CW’s Arrow has emerged as an effective vehicle for adapting DC Comics characters to a broad audience. Like the Marvel Cinematic Universe before it, the creative minds behind Arrow built their world by mixing decades of comic book adventure. Free to pick and choose, they adapted with an eye toward creating easy entry for new consumers and maintaining the loyalty of established fans. The recent appearance of Amanda “The Wall” Waller, on Arrow highlights the fact the current comic book culture is filled with questions linked to identity and gender. In deciding to adapt this character, the producers have entered into that dialogue. Taking their cue from the 2011 reboot called the New 52, Arrow’s Amanda Waller is a marker of larger identity concerns.

Figure 2: Suicide Squad #1 (2011)

The New 52 restarted DC comic publications from the beginning. Complaints about this reboot have focused on missed opportunities. Critics point to uneven characterization, failed opportunity linked to diversity and the reorientation towards new (hopefully younger) readers by abandoning continuity. These complaints are understandable, but perhaps unfair. In 1985, the company revamped the publication line with its Crisis on Infinite Earths mini series. Often lauded by fans, it was greeted with complaints as well. History has proven that story a milestone. With this in mind, we may see “The New 52” lauded for the push toward genre variety and the integration of formerly sacrosanct characters from Vertigo, the publisher’s mature reader line, back into the mainstream comic universe. Whatever history’s judgment, the immediate media spotlight has and will likely continue to question the depiction of female characters.

Concerns about gender and representation in comics are not new. However, in the context of the 2011 reboot, the re-imagined overtly sexualized look and actions of female characters such as Starfire and Catwoman triggered protest. Adding to these concerns, products, drawn from comic book source material, reflect a dynamic of gender objectification long cited by critics. In particular, the outcry over the failure to produce a Wonder Woman film and criticism about Rocksteady Studios’ depiction of Harley Quinn and Catwoman in its Arkham game franchise has troubled fans.[2]

Arguably the transformation of Amanda Waller is a crucial part of this dialogue. Introduced in 1986, the comic book Amanda Waller is an African-American middle-aged woman with a heavy build working as a government bureaucrat. She is a unique example of a black female authority figure in mainstream superhero comics. Her serious demeanor and steely determination managing a government-sanctioned task force called the Suicide Squad made her a fan favorite. Effective and dedicated, Waller commands the respect of villains and heroes alike. Animated television and film appearances have further embellished Waller’s status among fandom.

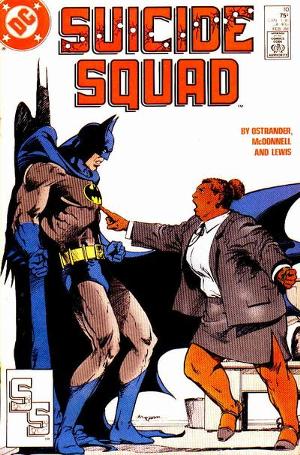

Figure 3: Suicide Squad Vol. 1. #10 (1988)

In revamping the publication line, DC editors made decisions designed to make character more accessible to a broader (less expert) reading public. Clark Kent/Superman is no longer married to Lois Lane (quasi-damsel in distress). Instead, he is dating Wonder Woman/Diana Prince, creating the ultimate “power” couple (Couldn’t help myself). Abandoning the Superman /Lois Lane relationship highlighted an edict that marriage is prohibited in this new status quo. This stance was perhaps made more frustrating because it was only fully articulated in the midst of a public furor over the editor’s decision to derail the same-sex marriage of Batwoman (Kathy Kane), the publisher’s most prominent lesbian character. The tumult surrounding that decision and the continued concern over female character placement and representation prompts me to ask, “What about Amanda Waller?”

Waller transition in the New 52 has received comparably minor protest. Arguably, while heroes and villains deserve the main scrutiny on a comic page, Waller’s transformation has a greater impact because of her unique status as a woman of color in a position of authority. The lack of concern about Amanda Waller’s presentation highlights gender and race intersectionality.[3] Articulated by black feminist intellectuals such as Frances M. Beal and Alice Walker, the interlocking nature of gender and racial bias creates overlapping barriers linked to race and sexism for women of color.[4]

Arguably, Amanda Waller has been affected by gender and racial expectations since her introduction. The original characterization could be seen as leveraging the nineteenth century mammy stereotype to great effect. Waller was a sexless maternal figure who valued her superior’s goals, but showed disdain for the team that acted as her quasi-family. Unconscious and unspoken, Waller’s placement as a “strong” and “principled” bureaucrat loyally working for the government confirmed some assumptions. Yet, with depictions of African-American women in the 1970s caught between a normalizing figure such as Diahann Carroll’s single mother professional in Julia (1968-1973) and Blaxploitation inspired icons such as Pam Grier’s tough vigilante Coffey (1973) Waller’s debut in the 1980s struck a more balanced note in a social and political landscape shaped by warring conservative and liberal views of African-American life and culture.

Neither objectified nor objectionable, there has been a consistency to creator’s attachment to Waller as a supporting character. Always in the background, always working for the “greater” good, her experience compounds the critical assessment that minority characters in comics are only allowed to function within a limited assimilative framework. Now, younger and more traditionally beautiful, Waller does not have the same gravitas. Waller’s function remains the same, but her appearance now creates a radically different context to understand her. Like other female characters in the New 52, her physical beauty brings her more in line with male expectations, but in her case those expectations have an added layer of racial exoticism. Now seductive as well as powerful, the new Amanda Waller hovers between a “predatory” Jezebel and a “malicious” Sapphire stereotype. At once desirable (Jezebel) and cruel (Sapphire), the new Amanda Waller carries the full weight of gendered racial expectations in a manner that does little to differentiate and everything to limit her character. The fact that this Waller has made the jump to Arrow reinforces the transformation in the pop culture landscape. Still, Amanda Waller’s transformation is a marker of a conversation we are not having gender and diversity in comics.

[1] Robin S Rosenberg and Peter M. Coogan, What Is a Superhero? (Oxford University Press, 2013).

[2] It worth noting the recent Arkham Knight (http://www.ign.com/videos/2014/03/04/batman-arkham-knight-father-to-son-announcement-trailer) game trailer featured a redesigned Harley Quinn that is arguably less problematic.

[3] “Race/Gender/Class ‘Intersectionality’,” accessed March 16, 2014, http://www.uccnrs.ucsb.edu/intersectionality.

[4]Frances Beal, interview by Loretta Ross, video recording, March 18, 2005, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, tape 2.

Julian Chambliss is Associate Professor History at Rollins College and co-editor of Ages of Heroes, Eras of Men: Superheroes and the American Experience.

Etta Candy from Wonder Woman has also been slimmed down over the years. Pop culture in general, and definitely superhero comics too, is uncomfortable with images of women who aren’t slender and conventionally attractive.

I’ve been thinking about Etta Candy lately. I read the Wonder Woman Archives, Volume 1, a few weeks ago, and Etta Candy is one of the most consistently entertaining elements of the early Wonder Woman stories. She is hysterical! I’ve read a few scattered Golden Age Wonder Woman stories over the years so I already knew about and liked the character, but I’ve never seen enough of her to realize how important she might have been to the success of Wonder Woman as a series.

Meanwhile, Etta Candy in her later incarnations is pretty bland. They thinned her down and got rid of her candy obsession and bleached her of the things that made her interesting. I realize the original Etta Candy characterization is an over-the-top fat girl stereotype, but they went too far when they modernized her. They should have kept the “Woo! Woo!”, that’s for sure.

I haven’t seen skinny Amanda Waller (except in the Green Lantern movie, and I’ll give them a break there because she was played by Angela Bassett), but it seems a shame that DC is embarrassed by the version of Waller in The Suicide Squad of the 1990s (it was a rare breath of fresh air in decade of bad bad bad comics) and felt the need to make her like every other skinny or stacked female character.

“Waller transition in the New 52 has received comparably minor protest. Arguably, while heroes and villains deserve the main scrutiny on a comic page, Waller’s transformation has a greater impact because of her unique status as a woman of color in a position of authority. The lack of concern about Amanda Waller’s presentation highlights gender and race intersectionality.”

This is not true. There was widespread anger over Amanda Waller’s revamping on mainstream blogs with far more circulation than HU, often in concert with discussons of Quinn and Starfire. Much of it was by actual women and minorities! There were essays, multipage discussions, uproar on social media, parody comics (alas I cannot find the links right now). This included discussion of Angela Basset being cast as a thin Waller in Green Lantern.

Here are a few links:

http://www.racialicious.com/2011/09/15/epic-fail-of-the-week-dc-comics-drops-the-ball-on-the-wall-in-suicide-squad/

http://comicsalliance.com/amanda-waller-skinny-thin-reboot/

http://www.themarysue.com/amanda-waller/

http://robot6.comicbookresources.com/2011/09/another-casualty-of-dcs-new-52-amanda-wallers-weight/

http://www.bleedingcool.com/2011/09/15/adam-glass-on-the-thinner-younger-amanda-waller-in-suicide-squad-1/

http://daggerpen.tumblr.com/post/57638593706/this-isnt-about-thin-shaming-amanda-wallers-new

https://www.blastr.com/2011/09/latest_dc_reboot_controve.php

http://amptoons.com/blog/2010/04/13/the-thinning-of-amanda-waller/

http://dcwomenkickingass.tumblr.com/post/10252900677/awuique

It’s even mentioned in passing in an otherwise neutral presser about Arrow: http://screenrant.com/arrow-season-2-spartacus-star-cast-as-amanda-waller-antv-360066/

The one place that doesn’t appear to have discussed Waller is The Comics Journal; while it’s the HU’s nemesis it does not represent all of fandom, not even the smart part.

I don’t know if this is poor research or deliberate misrepresentation. Either way, pretending the prior conversation was minor doesn’t serve the topic, only the author’s pretense of observing what was overlooked which involves silencing many other voices.

The Hooded Utilitarian does well at dissecting what I call Fandom Bullshit: a mythic view of one’s own cultural consumption distorting one’s ability to think critically. It was spot on about how R. Fiore’s inability to acknowledge Pogo’s racial politics is rooted in his own fan identity needing a pure fan object to reflect well upon himself.

Slaying mundane fandom bullshit is part of the HU pesona. Blogs always have some unifying narrative, and the mock superhero name contains a mock heroic story: writing as a “Hooded Utilitarian” means fighting against certain bullshit and for certain deeper insights.

The problem is, just like so many superheroes, this heroic nature is also the dark side. HU is unable to recognize it’s own Fandom Bullshit – Alt-Fan Bullshit in which one’s own consumerism must be a superior, worthier sort than the common consumption. Comic Fans may hate how the new 52 because sexualizes Harley Quinn, but only a Hooded Utilitarian has enough intersectionality powers to note the sanitizing of the heavyset black woman.

This is also reflected in the underrated/overrated discussions which use convoluted definitions of how something rates to permit successes such as Bloom County and John Christopher to still be What They Don’t Get. It exaggerates (and simplifies) the status of common (but not singular) opinions into villainous strawmen of Things Everyone Else Thinks to be clobbered by Fists Of HU Dissent.

Which is fine, but I think it’s something HU needs to address, in addition to strawmen exaggerations, it leads to overly reductive/broad arguments being used to criticize the same, and assertions being poorly substantiated due to a presumed uniqueness. HU is an often excellent blog for pop cultural critique, but the superheroic thinking can play it false. [For example, Bloom County’s own significant failings, particularly the sexism, got a near Fiore denial in the loving tributes of the roundtable.]

Ha! I like that response. Links the Waller transformation to other fanboy controversies like organic webshooters and a black Johnny Storm and Norse gods.

Hey HF. First of all, Julian has never written here before, and he is guest posting through PencilPanelPage, so showing up and accusing him of being part of some sort of HU hive mind seems a little ridiculous.

Second, your comment seems to assume that he is not himself a minority. I’d suggest you rethink that.

The underrated/overrated discussions are really not supposed to be taken all that seriously. And, like, they’re discussions. People disagree with me. All the time.

Finally, TCJ is not in any way this blog’s “nemesis”. Lots of people who write here also write there. They have lots of excellent articles at TCJ (a number of which showed up in our best of years comics criticism.) I disagree with folks over there sometimes, but I certainly don’t think that means that TCJ is bad, or that I even dislike their editors (on the contrary, I think Dan and Tim have improved the site immeasurably since I was there.)

Pointing to other discussions of the topic is certainly useful and helpful. However, I really do not want Julian to have to deal with some sort of generalized discussion of the blog and what is or is not wrong with it based on editorial decisions with which he has nothing to do, and on a community that he has just joined. So, if you have more to say on that topic, I’d suggest you save it for the weekend roundup post. Or put your comments about it on the last one if you can’t wait. Thanks.

Hey Hooded Fanboyism! I liked your comment. Seriously, though it made me feel like maybe you haven’t read my posts on here about stuff like Black Lightning and She-Hulk.

But yeah, as someone who has never been much of a DC comics reader, I had never even heard of Amanda Waller until the controversy over her transformation – so in reading this piece I, like HF, was surprised at the characterization of the degree of fan response.

I’ve long been a fan of Waller, thanks for writing her up. And while I found the Hood Fanboyism post a bit harsh, I appreciate the link roundup.

Julian, I’m late weighing in, but thanks for this guest post. I actually wasn’t familiar with Waller or the changes that DC made to her character, so I appreciate this context. I can’t help but wonder how people responded to her debut in the 1980s. I’m thinking that in addition to the Blaxploitation backlash, this also overlaps with the Cosby Show years… How did DC leverage the mammy stereotype during those early issues to make her such an admired character?

Thanks for introducing me to this character and to these issues, Julian. Like Qiana, I’m not familiar with Waller or with her early appearances in The Suicide Squad, but I’m also curious about how she fit into the American pop cultural landscape of the late 1980s–the Cosby era that Qiana mentions. Now I’m thinking of how the original version of the character might have functioned in the context, for example, of popular African American actresses such as Nell Carter from Gimme a Break! or Marla Gibbs on 227.

I’d also be curious to go back and read those Suicide Squad issues to compare how Waller is portrayed in comparison to the character Sonia Stone from Michel Fiffe’s new sci-fi/superhero series Copra. Have you read it? He has the first issue available for free on his website. I wonder if Stone might be modeled somewhat on Waller:

http://michelfiffe.com/comics/copra/index.html

The sketchy, dynamic weirdness of his designs reminds me of Frank Miller’s Ronin, and the narrative has the same forward-thinking qualities of some of the other independent superhero and fantasy conics of the 1980s (I’m thinking of Chaykin’s work, Reggie Byers’ Shuriken, Bill Willingham’s Elementals, Matt Wagner’s first Mage series, notably in Wagner’s use of Edsel, a young African American woman, as a central and much-beloved character). We get an especially poignant and complex look at Sonia in issue #7, in which she and the rest of the team mourn the loss of one of their key members. It’s a very cool series, and worth reading in the context of the questions you raise here about issues of race and gender in superhero narratives.

Aha! So, according to this interview, Copra is indeed a riff on the 1980s Suicide Squad series…

http://comicsalliance.com/copra-michel-fiffe-interview-suicide-squad/

I think the suggestion that I’m attempting to present some particular view associated with HU is interesting. I’m not, but I take the comments as a testament to the community’s engagement. It was not my intention to suggest no one had commented on Amanda Waller (or other female characters) being transformed. I believe I said, and I continue to believe, that there is relatively less sustained engagement around Waller’s transformation. My assertion is and remains that Waller’s transformation and the nature of the engagement around it, highlights compounding deficits created by race and that remains in the background of gender discussions. Scarcity in term of racial diversity combined with these established gender concerns make Amanda Waller more, not less significant in my mind.

To me, Waller’s inclusion in the CW’s Arrow highlights this point. This appearance marked a synergy of the New 52’s characterization into the mainstream. Attempted in Green Lantern, it arguably, succeeded in a manner of greater import because television remains a mass medium. By including the “new” Waller, the expectations for what diversity can be expected in superhero comic books is diminished. As we continue to struggle with questions of diversity, this characterization narrows audience expectation making Waller’s position worth noting and questioning. As the comments suggests, Amanda Waller and Etta Candy New 52 introductions were seen as examples of gender standardization associated with female objectification (in Candy’s case shifting her race can be seen as broaden representation). Yet, my question, and it was a question, is why isn’t Amanda Waller’s transformation a bigger debate.

As we call into account the failure of the medium, discerning the depth and scope of grievance associated with representation is an injurious process that risks causing harm even as it attempts to create a context for change. Yet, as fans call on adaptors to “remain true to the source material,” I’m reminded of Waller’s centrality. I take the character’s appearance (in her original incarnation) in the trailer for Batman: Assault on Arkham (http://youtu.be/ZN_jlZc6fzA) to be an affirmation that some element of fandom remains invested to her traditional characterization. Thus, Waller’s adaptation spotlights the larger and more complex identity discussion. I hoped the question would open the path to a greater discussion.

Thank you!

I write only to request that Julian Chambliss be invited back to write again. Excellent article!