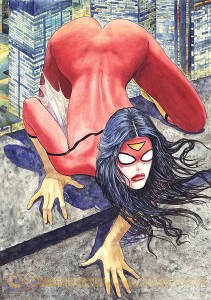

So everyone is no doubt aware of the Milo Manara Spider-Woman variant cover art controversy that occurred a couple of weeks ago. Marvel’s commission of the cover, and its subsequent reaction to the backlash, was sadly typical of a mainstream comics industry that seems to want to embrace its large and growing female readership yet seems utterly incompetent when it comes to actually doing so.

So everyone is no doubt aware of the Milo Manara Spider-Woman variant cover art controversy that occurred a couple of weeks ago. Marvel’s commission of the cover, and its subsequent reaction to the backlash, was sadly typical of a mainstream comics industry that seems to want to embrace its large and growing female readership yet seems utterly incompetent when it comes to actually doing so.

Now, I don’t want to talk about Manara’s Spider-Woman cover art for any of the standard and by now familiar reasons. I don’t mean to suggest that the issues relating to the depiction of females in comics raised by the incident are not worth attending to – quite the contrary. But one public comment regarding the incident got me thinking about a different issue.

On September 2, Kelly Sue DeConnick – the current writer of Captain Marvel – made the following statement in an interview when asked about her take on the cover:

“The thing I think to bear in mind is Jess is not a real person – her feelings are not hurt by that cover.” (full video interview here)

Now, this is certainly true.

But we shouldn’t forget certain claims are objectively (even if only fictionally) true of a fictional character (e.g. Jessica is a superhero) and other claims are objectively (again, even if only fictionally) false of fictional characters (e.g. Jessica lives on the moon), regardless of the fact that the character is question doesn’t actually exist. In particular, the production and publication of Manara’s cover now makes it fictionally the case that Jessica (at least once) poised herself atop a building, in a body-paint version of her costume, ‘presenting’ herself (in the biological sense of the term) to anyone in the city who might want a look. Regardless of how we might want to re-construe or reinterpret the art, this is what it in fact depicts.

But we shouldn’t forget certain claims are objectively (even if only fictionally) true of a fictional character (e.g. Jessica is a superhero) and other claims are objectively (again, even if only fictionally) false of fictional characters (e.g. Jessica lives on the moon), regardless of the fact that the character is question doesn’t actually exist. In particular, the production and publication of Manara’s cover now makes it fictionally the case that Jessica (at least once) poised herself atop a building, in a body-paint version of her costume, ‘presenting’ herself (in the biological sense of the term) to anyone in the city who might want a look. Regardless of how we might want to re-construe or reinterpret the art, this is what it in fact depicts.

Of course, as DeConnick notes, Jessica’s feelings aren’t hurt by this – not even fictionally. She isn’t fictionally aware that an artist decided that she would expose herself this way. On the other hand, she now just is the sort of (fictional) character that – perhaps in a single moment of questionable judgment – is willing to engage in some rather extreme exhibitionistic behavior. In short, the incident depicted on the cover is now part of how we understand what sort of person Jessica is.

Given this, we can meaningfully ask: Did the Manara cover (fictionally) harm Spider-Woman? And I think the answer here is uncontroversially “yes”. Whatever Jessica’s motivations for engaging in the behavior depicted in Manara’s art, this contribution to Spider-Woman’s narrative seems to be a negative contribution to her character – a representation of vice, not virtue.

The more important question to ask, however, is perhaps this: Independently of the other kinds of harm undeniably caused by the cover (and well-covered elsewhere), should Manara feel bad for producing this image because it (fictionally) harms Spider-Woman (or should Marvel feel bad for commissioning the image, or should we feel bad for consuming it)? Have we (i.e. Marvel, or Manara, or readers, or some combination of the three) done something morally wrong by adding this incident to the story of Jessica’s life? In short, should we care that we have done something objectively (albeit fictionally) harmful to a fictional character? Is there any sense in which we have moral responsibilities to fictional characters at all?

Of course, characters are harmed via depicting them doing non-virtuous things (making them non-virtuous characters) all the time – we call them villains or antagonists, and we need them for at least some sorts of story. But here the fictional harm done to Spider-Woman was not done in the service of any identifiable narrative needs. It was done for no reason at all, except presumably titillation. So unlike the case of villains, there is no story-related reason to alter Spider-Woman’s character in this negative manner.

So, was Spider-Woman harmed in the making of this cover?

Note: I have simplified a number of issues in the above in order to facilitate my main question:

- The narrative content of cover art does not always straightforwardly depict events that we are meant to take to have actually occurred in the narrative contained within the comic – cover art can play all sorts of other commercial or aesthetic roles in addition to straightforward storytelling (see my previous post here).

- I have assumed that unsolicited exhibitionism is, all else being equal, morally bad (since, for example, it might harm those exposed to it against their wishes).

If one is unwilling to grant me the simplification in 1, or refuses to grant 2 for the sake of argument (since the questions I am trying to raise is a larger one about the moral properties of fiction), then feel free to imagine a relevantly similar depiction of a until-now (mostly) heroic fictional character engaging in morally unacceptable sexual behavior for no reason other than, perhaps, the sexual gratification of the reader, and where that incident is depicted in the main body of the narrative.

It’s hard to get my head around the idea of real harm coming to a fictional character, I have to admit. In this case, I guess I feel (as you suggest) that covers like this aren’t meant to be part of actual character development.

I guess you could also ask whether a cover like this and all the publicity might help the character? Will the series do better because it’s gotten so much mainstream coverage?

Spider-woman is not exhibiting herself to anyone in the context of the cover, she’s in a private location on the roof. Plus she’s fully clothed (though in skin tight costume, granted).

I think your article seems to be asking the wrong questions and approaching this from a not helpful paradigm. Saying Spider-woman is doing something “morally unacceptable” in that cover is really, really silly.

(I feel fairly neutral regarding to whole cover controversy, but the edge of moral panic in your post makes me want to defend the cover)

Pallas,

The point about what is depicted in the art is an issue of interpretation, and hence allows for much wiggle room. But still I have to stand by my reading. First, it’s not the case that she is in a secluded location on a rooftop – she is instead positioned so that her buttocks are hanging over the edge, with hundreds of windows from which bystanders might yet a clear view explicitly depicted in the art. Second, the whole ‘she’s wearing her costume, but it’s skintight and Manara just wanted to draw it this way’ line doesn’t hold up: Manara is incredibly gifted at drawing the folds, seams, and bunching of fabric (when he does draw clothing), so his choice to include none of that here, plus the dappled appearance of the costume pattern that is there, seems explicitly to depict nudity and body paint (of course,manara would likely deny this reading if asked – that doesn’t necessarily make it wrong).

Regarding the moral panic issue: that was a tone I was explicitly trying to avoid. I think there is little ambiguity in what the art depicts (others, including yourself, are free to disagree). Once this is granted, however, there are interesting ethical and moral questions regarding the effects of such art on the fiction (distinct from the questions already asked elsewhere about the art’s effect on the audience). I don’t see how raising such questions amounts to moral panic.

And it is worth noting that the assumption that the sort of exhibitionism that (I think) is depicted in the art is morally objectionable is just that – an assumption (as indicated at the end). But I suspect more people will agree with it than not.

I don’t see any moral panic in Roy’s post! He’s just interested in the question of the moral status of fictional characters. (If you read, he says, if you don’t think there’s anything immoral about public exposure, then figure out some other action you do think is morally problematic.)

In terms of the logistics; it’s not really clear that Spider-Woman is wearing anything; she seems to be in body paint rather than a costume. And the privacy of the location is questionable; she’s outside, people in other buildings can supposedly see her. Also, how did she get up there?

I’m with Pallas. The idea that this image “harms” a fictional character seems really dubious, and the argument that it “really happened” because it takes place on an official cover published by Marvel is kind of easily refutable: did Hulk once become Donkey Kong? Did Captain Marvel turn into a fox-lady at some point? Did the Avengers all become babies? Did Wolverine once cut his own ear off in imitation of Van Gogh? Of course not; these are all artists’ depictions of the characters done for variant covers, just like Manara’s was. Was his image objectionable? Sure. Should we be outraged, not because it’s gross, but because it has altered the character’s history to make her more slutty or something? That question doesn’t even make sense.

I expect we’re all pretty tired of this conversation by now (I know I end up shaking my head when it contorts itself into this sort of ridiculousness), but I think it’s interesting to step back and see how it almost certainly blew up much larger than Marvel ever thought it would. This was a variant cover that wasn’t going to be available to very many people; actually buying a comic with this cover would probably cost something like $100. That’s a pretty standard thing in comics, so Marvel probably thought nothing of it, figuring most people wouldn’t even see it. But while it wouldn’t be widely available in comic shops, it’s pretty easy to spread online, a perfectly distributable example of everything wrong with mainstream comics. I doubt they ever expected so many people to be talking about it, so it’s kind of fascinating to see them try to downplay it and do some damage control. Maybe it will end up making a difference and causing artists and publishers to consider the effect their published art has on people. Or maybe they’ll just tamp the objectification down to “acceptable” levels and go on with their business as usual. I wouldn’t hold my breath waiting for any real change, but it’s interesting to consider.

If you’re reading her as wearing only body paint… I guess I could perhaps see your argument.

But it seems to me that’s its morally iffy and potentially creepy to say that a clothed woman is participating in exhibition or public exposure just because you don’t like how tight her clothing is. If that’s not what your saying, however, then I guess we don’t disagree.

As for the body language, she just climbed the roof, when you turn away from people folks can see your clothed butt- again not public indecency unless you are positing she’s not actually wearing clothing. Those buildings in the distance are pretty far away, I don’t see any indication of voyeurism suggested from the composition.

And if we’re talking about artistic intent the real “artist” is Marvel comics, who commissioned the painting, and as matthew has suggested I highly doubt that Marvel comics intends the cover to be a sign that continuity now reflects sexy naked exhibitionism from Jessica whatshername, whatever the interchangeable freelancer they hired this week may or may not be going for. So it seems a stretch to claim that cover has implications on continuity, as Brady states.

I’ll also add if you really think the Marvel editors who approved that drawing thought she was naked in body paint- you’re probably pretty out of touch of how Marvel editors read and interpret comic art.

Not sure what the Marvel editors have to do with it? Lots of people who saw it thought that. And looking at it, it seems like a fairly reasonable interpretation.

I’m objecting to Roy’s focus on the long term impact on Spider-woman while doing a reading of the individual art.

Either the painting is a stand alone work with no power to “hurt” other Spider-woman works of art, or the painting is a contribution to a body of Spider-woman narrative overseen by the editors, ultimate authority over Spider-woman continuity. Roy is trying to have it both ways- arguing about impact on Spider-woman’s “continuity” while focusing only on the contribution and intent of Manara.

If you’re that concerned about the ongoing impact on the character- I’m saying you need to look at editorial intent, not the individual artists intent.

I’m not familiar with this controversy at all (ha!) but Kelly Sue DeCommick’s comment is disingenuous. The salient issue is not how the cover makes a fictional character feel; it’s how it makes real people feel.

I don’t get this line of questioning, but even taken on its own terms, the question contradicts itself. Is a fictional character morally compromised–and “harmed”–by some old man’s drawing? I wouldn’t have thought it possible to blame the victim without giving her any agency whatsoever, yet here we are. You can’t have it both ways. If you take the cover to mean that Spiderwoman as an exhibitionist is canon or whatever, then you have to assume that was her personal choice.

Pretty low bar for “fairly reasonable interpretation.” I’m not up to date on recent Spider-Woman stories, but is there anything in her character that would suggest that Spider-Woman would ditch her costume for body paint and “present” herself to the residents of the building opposite her?

I think the more reasonable interpretation is that it is an inaccurate drawing of what a woman wearing a skin-tight costume would look like. Super-hero comics are full of inaccurate drawings, and the idea of those inaccuracies having any impact on the stories/world of the character is ludicrous.

For example, take all of those awful poses that a real woman could not attempt without a broken back. Does anybody seeing one of those covers think “Wow, I can’t believe that they broke Princess Diana’s back?” What about all the times Batman’s cape changes length from cover to interiors, or from panel to panel? Or bad foreshortening that implies a character has limbs that are way too short or way too long? Are we to take those examples as part of the character’s storyline?

It’s more reasonable to assume that those are, for better or worse, intentional or not, examples of a choice by the artist. Sometimes it works (great drawings of Batman with a 30ft cape), sometimes it doesn’t (impossible postures).

The idea that a cover with inaccurate rendering of a costume can harm a super-hero property just doesn’t make any sense. Grant that the cover means that Spider-Woman decided to flash a skyscraper or two in continuity. Super-heroes, more than any other genre, are characters with pasts that are rebooted, reincarnated, explained away and ignored. At one time Hal Jordan was a mass murderer, I’m not 100% sure what happened, but he seems to be a member in good standing of the Justice League.

Matthew, Pallas, and Dean: as I thought I made clear in the final clarificatory note in the original post, the point was to try to raise a question about our moral obligations to fictional characters, and I used Spider-woman as a particularly salient and topical example. I also suggested how one could imagine an alternative clear-cut case of the sort I had in mind, if one disagreed with my particular reading of the Manara cover (and I mentioned exactly the sorts of worries you have in fact discussed extensively). So I am not sure what the point of all this is with respect to the intended (and I think clear, since Noah immediately chimed in to highlight it!) point of the post, which concerned whether we have certain sorts of moral obligations with regard to how we treat fictional character.

Pallas: saying that Marvel comics is the real artist due to the fact that they commissioned the cover strikes me as about as plausible as saying the Catholic Church is the real artist of the Sistine Chapel murals because they commissioned Michelangelo. On a related note, claiming that Marvel Editorial determine what counts as canonical by fiat ignores the actual history and function of the notion of canonicity, which is dynamic, negotiated (between producers and consumers), and participatory (see work by Reynolds, Brooker, and me). Of course, this cover art likely isn’t (or better: won’t turn out to be) in any sense canonical. But not merely because Marvel said so.

Kim: I never meant to imply that this was the ‘salient’ issue, or the most important, or whatever. On the contrary, as I alluded too, the most pressing issue is no doubt the impact this cover has on gender in comics and it’s fandom. But that issue has been covered elsewhere, in depth (as some above have noted, while inaccurately characterizing me as adding more to that same debate).

Matthew and Dean: I agree that interpreting the role that non-literal content plays in cover art is tricky and complicated – in fact, I make points similar to yours in the older post on comics covers linked above. That being said, it seems plausible to me that, for example, Rob Liefeld does not intend his drawings to be drawings of women with shattered spines, so it is implausible to interpret them as such, while Manara did (I suspect) intend this drawing to look like a woman posing in body paint, so it is reasonable to interpret it thusly.

I wrote about the cover here a bit back, if anyone’s interested.

Here is a more explicit, and perhaps more helpful, version of the sort of argument that I hoped to explore:

1) Insofar as we are making art in the first place, and insofar as we have the option, we have a (moral?) obligation to make good (or better) art rather than bad (or worse) art.

2) Art that depicts morally objectionable actions or situations, for no discernible narrative or aesthetic purpose, is prima facile worse than art that does not.

3) The Manara Spider-Woman cover arguably depicts a heretofore good character performing morally objectionable actions, for no discernible narrative or aesthetic purpose (unless titillation counts as aesthetic).

C) Thus, the creation of this particular artwork involves actions (on the part of the creator) that are (morally?) wrong or objectionable.

The further thought was that we could, perhaps, explain and understand this phenomenon further in terms of the wrongness stemming from harm done (fictionally) to the character – that is, the artwork is objectionable (in this sense at least) because it makes Spider-Woman a worse person.

In short, I was wondering whether (not arguing that!) the cover is objectionable not only for the effect it has on readers, but also in virtue of the effect it has on the relevant fictional character.

Roy

I raised the Green Lantern example as evidence that there really isn’t any story or story element than can’t be undone or ignored. It would take someone like Roy Thomas about 10 minutes to come up with multiple reasons why that image, in continuity, doesn’t represent Jessica Drew/Spider-Woman flashing Manhattan in body paint. I suppose, in your take on canon (which sounds about right to me) that some groundswell of the consumers of the Spider-Woman property could place that cover into canon, even then so what?

I agree that Manara intended that picture to look like a woman posing in body paint, I just don’t think his intention, or the result matters without some sort of in story reason why that would be the case.

I don’t think there are any moral obligations to fictional characters, particularly mainstream super-heroes, who exist primarily as intellectual property to be exploited (like that cover) by corporate ownership. Spider-Woman is a particularly interesting case in that the character exists because Marvel Comics wanted to secure the trademark to the name, to protect the (still) more valuable Spider-Man property.

Alas, the Manara cover may not have been the best example, Roy. Too controversial; people kind of inevitably start talking about the other stuff. (I think it’s also tricky since the immorality from the perspective of the character isn’t clear enough…wearing body paint doesn’t seem like it’s in itself an immoral act.)

Trying to think of a better example…maybe something like these? Are you damaging Batman by having him kill people?

“The Manara Spider-Woman cover arguably depicts a heretofore good character performing morally objectionable actions”

This is where’ you lose me-

it’s like saying “This isn’t necessarily offensive,… but just for the sake of argument let’s all assume its offensive and talk about how offended we and wail and gnash our teeth”.

It’s like Pavlov’s literary criticism. I don’t think throwing the word “arguably” around makes it reasonable to follow your assumptions to what follows. That cat isn’t necessarily dead.

There is at least one claim here that is an obvious falsehood, viz. this:

“Did the Manara cover (fictionally) harm Spider-Woman? And I think the answer here is uncontroversially “yes”.”

Whatever the right answer is, it’s obviously not uncontroversial.

You know, Kelly Thompson wrote a thing last year when DC declared that Batwoman was not going to get same-sex married, where she said re. a potential boycott, “why should a character like Batwoman be punished because of something that has nothing to do with her.”

At the time, I thought this was crazy, to think that readers in the actual world could “punish” a fictional character. But I’ve got to say, having read this, I still think it’s crazy.

To say a bit more: it looks prima facie to be a category mistake to import extra-diegetic facts into the diegesis, not least because you easily create contradictions that way.

For instance, Marvel Comics exists in the “Marvel Universe” (this has been shown several times over the decades). And, although this has not (I don’t think) been explicitly shown, it’s easy to infer that comics published in the Marvel universe don’t reveal the secret identities of their characters, otherwise they wouldn’t be secret any more.

So it looks, if we reason analogously to how you’ve argued, that both these statements are true:

In 2014, Marvel published comics showing that Peter Parker is Spider-Man

and

In 2014, Marvel did not publish comics showing that Peter Parker is Spider-Man

Or, similarly, Peter Parker was a teen in the 1960s, and Peter Parker was not a teen in the 1960s (since he hadn’t been born yet, according to current timelines). Or, similarly, the Green Goblin is solely responsible for killing Gwen Stacey. And John Romita and Gerry Conway killed Gwen Stacey. Et cetera. We could go on like this all day; indeed, all millennium.

…I don’t know anything about the philosophy of fiction, but my first guess would be that truth-within-the-fiction is standardly treated as a modal operator, where the following two inferences are invalid (using “TWTF” to represent the modal operator):

If p then TWTF p

and

If TWTF p then p

For at least some ps, these are false. In fact, for a whole lot of ps.

There’s a grand philosophical tradition of making claims that are radically, crazily, counter-intuitive. But typically these are offset by (at least putative) theoretical benefits, so — what’s the benefit here? You’ve bitten the bullet, but what on earth for?

…all of which is to say that I really enjoyed this post.

Jones:

I agree that inferences of this form are not generally truth-preserving. But that doesn’t mean that facts about the actual world don’t entail facts about what is true in the fiction. After all, we certainly want to accept lots of claims of the form:

If author x wrote P then TWTF(P).

There is no category mistake here – rather, this sort of relationship between diegetic facts and extra-diegetic facts is just part of the story regarding what fictions are, where they come from, and how they work.

Here I am interested in a particular claim of the form:

1) If creator x depicts previously virtuous character y performing immoral act z then TWTF(character y has been harmed).

Or perhaps:

2) If creator x depicts previously virtuous character y performing immoral act z then TWTF(character y is less well off than he/she was.)

(Setting aside whether the example I chose was a wise one, it isn’t all that implausible that some claims of this form could be true.)

The (admittedly more controversial) thought was whether we might also accept something like:

3) If creator x is responsible for making it the case that TWTF(character y is less well-off than before), and there is no narrative or aesthetic justification for doing so, then creator x has done something morally objectionable.

Now, I am not necessarily endorsing 3 (I am tentatively endorsing something like 1 or 2). But 3 doesn’t seem like a crazy claim to me – rather, it seems like an open question worth asking.

Re: 3, for a start, a lot hangs on what counts as narrative or aesthetic justification. I’m now going to tell you a story.

“Once upon a time, there was a guy named Jones. Jones was horribly tortured and killed. The end.”

I call this story, “Lo, There Shall Cometh A Guy Named Jones”, but let’s call it “Lo” for short. On the face of it, Jones’ fate doesn’t have much aesthetic or narrative justification; in fact, the story as a whole doesn’t have much aesthetic or narrative anything. (It might have dialectical justification, in the current context.) Have I done something wrong in telling the story?

And then a lot depends on what it it is to make it the case that TWTF p. Obviously if Marvel publishes a story in which Spider-Woman punches Stilt-Man in the face, then Marvel has made it the case that Spider-Woman punched Stilt-Man in the face. But what about if I write a fanfic in which that happens? And then what about if I merely imagine that that happens? Do I do something wrong in idly imagining that ill fate befalls my enemies, and, if so, is it because I am harming them (rather than, say, because of the corrupting effect on my own character, or because such imagining increases the probability that I will actually harm them?)?

The reference to a “body paint” version of the costume seems a bit pointless – isn’t that how most artists have drawn superheroes of both genders over the years, as nudes with a few lines added to represent the costume?

Don’t really have an opinion about harming a fictional character. Not least because I’m not sure it really makes sense to think of superheroes as single characters – they’re more a series of different – sometimes very different – versions of a character by various hands. That would have to for inconsistency… and how can you “harm” an image designed to register a trademark?

None of which is an attempt to justify that cover.

Or try this: imagine all your favourite fictional characters. Now imagine them horribly tortured and killed. Congratulations, you’ve just massively harmed all your favourite fictional characters. Maybe I’m the one truly culpable here since I tricked you into doing it, but (not least because I don’t actually know who your favourite fictional characters are) you’re the one who pulled the trigger and (to mix metaphors) you’re the one with blood on your hands.

Nya-ha-ha *twirls moustache, rubs hands together fiendishly*

Jones,

I agree with you that little harm comes from the sorts of examples you describe. In the story Lo I think someone who is sympathetic to the argument I sketched above might think you have done something less good than if you had told a similar story where something good happens to Jones, but that the story, and the imagined similar, but more positive variant, are both so insubstantial that any moral goodness or badness involved is insubstantial as well.

Now, in the argument I sketched in an earlier post, one crucial bit is that the badness is a result from violating some sort of maxim to produce good art. So harming a character need not automatically be bad – it is only when we harm a character when creating art. Since when I am imagining something I am not producing art of any sort, presumably I can’t be violating that maxim.

Fanfic is more difficult (partially because it is often art, even if often very bad art). Of course, fanfic isn’t canonical, so one move that could be made here is this: Fanfic doesn’t (and couldn’t) actually hurt the characters, since in some sense fanfic isn’t actually about the characters in the first place (it is instead about some sort of surrogates for the characters). But I am not sure about this.

So, the thread has apparently been hijacked by logicians,and I don’t know that I have it in me to read through the entire resulting detritus. However, I did want to say that I think the model you’re proposing for dealing with fanfic there at the end seems really problematic to me, Roy. In the first place, why should fanfic be given some sort of ontologically or morally different stance than corporate superhero comics? The folks writing corporate superhero comics didn’t create those characters. They happen to own them because of various contracts and IP arrangements, the ethical nature of which is often dubious, and the aesthetic worth of which is often even more dubious than that.

I don’t know that fan fic stories are actually consistently worse than mainstream supehero comics. But I would say that, bad or good, all fan fic is art.

Noah,

Well, the people writing approved Marvel stories are involved in ongoing, complex institutional arrangements that involve(d) the people who created the characters, while the authors of fanfic are not.

Nevertheless, I agree that fanfic is probably a more complicated situation, and my suggestion that we treat fanfic as about some other characters is almost certainly wrong (of course, I was only proposing it as one possible move for someone who wanted to adopt the argument I gave earlier in light of Jones’ worries). Of course, Sean seems to be suggesting that we have a new character each time a different author writes a story (but perhaps I am misunderstanding him).

At any rate, we do seem to treat fanfic as having far less authority than authorized stories when determining what is (fictionally) true of characters. So bad things happening to characters in fanfic might be immune from the sorts of worries I began with (assuming that those worries are on the right track to begin with!) But more needs to be said here, and at this point I am not sure what.

I dislike the whole idea of authorized stories, honestly. It’s one thing if you’re the creator — though really parodies and such without creator approval seem like they can be worthwhile/important too. If Joseph Andrews is worthwhile….

I’m not suggesting that we have a new character every time a new author writes a story, but rather that it doesn’t make sense to think of them as a single coherent character. I guess sometimes enough difference might make them effectively a new character though.

An obvious example of the top of my head – Frank Miller’s Daredevil is quite distinct from the early 70s version and a very different character to that in the Stan Lee/ Wally Wood issues, despite the same name and costume.

If you think they’re all a single character, aren’t you effectively just a comic book fan arguing for strict continuity?

Yeah, sorry, introducing fanfic was throwing a spanner in the works. What to say about characters that appear in different stories — that’s a tough one.

But let’s assume for convenience the intuitive position that, when Marvel publishes a comic featuring Spider-Woman (say) doing drugs and stealing candy from babies (let’s get off the sex thing), and I daydream about Spider-Woman doing drugs and stealing candy from babies, there’s at least some important sense that we’re referring to the same character.

The idea, then, that creating art has some special ontological status, that bestows moral significance on the characters that they don’t have in my mere imagining — that seems like magical thinking to me.

Let’s say I have a dream in which Spider-Woman does drugs and steals candy from babies — obviously I’m not morally culpable there, and it seems like you’d say there’s no harm done to SW there. Okay, so let’s say I have a dream journal, and I write down the dream. No harm there, I guess? Okay, now let’s say I publish the journal — hmm, maybe that’s like fanfic and you don’t know what to say about that. So, okay, now let’s say Marvel is so impressed by my dream journal that they buy it from me and publish it themselves, in a volume called Spider-Woman by Jones: Volume 1: Axis: The Epsilon Protocol Part 6: The Candy Incident: The Epic Collection.

All right, now, on the view you’re sketching, or throwing out for discussion, or tentatively suggesting, or arguablying, or whatever, somebody has harmed Spider-Woman at some stage. To which I know no better reply, than: pshaw. When was the all-caps ART created, and thereby the wicked deed done to her? Even if you deny my assumption that they’re the same character, we can ask a similar question: at some stage I was doing no harm to some characters, and then at some later stage I was (supposedly) doing harm to some other characters because I was making ART in which they were meanies — so when did it happen?

And I’ll just underline the obvious: the question is not whether I’ve done something wrong by creating aesthetically shitty art (I assure you, S-WbJ:v1:A:TOPE6:TCI:TEC would be awesome), or by upsetting real life people who live in the actual world and are fans of the character, or by contributing to a culture in the actual world in which women are dehumanised as sexual objects (or the candy-related equivalent), or by increasing the probability that impressionable teens in the actual world will steal candy from babies, or by damaging the “intellectual property”‘s long-term profitability for Marvel Entertainment, LLC (in the actual world). The question is whether, at some stage, I have harmed a fictional character.

No – the fictional character hasn’t been harmed if its aesthetically awesome. That’s magic for you.

As the last few comments have made clear, determining what counts as ‘being about Spider-Woman’ in the relevant sense is more complicated than my earlier suggestions.

Here’s one last attempt to elucidate the sort of distinction I had in mind. Take the various versions of Jones’ epic S-WbJ:v1:A:TOPE6:TCI:TEC mentioned: (1) Jones’ dream, (2) Jones’ private dream journal, (3) Jones’ online dream journal, (4) Marvel authorized version of Jones’ dream journal.

Now, in all four cases I am happy to admit that a character has been harmed (I actually have doubts that the dream or the private version of the dream are art, but that has to do with particular views I have about the nature of art, so I’ll set that aside). But the difference is that there seems to be a significant sense in which we care far less about the first two cases than we do about the fourth (the third case is difficult -see below) i.e. we take the harm done in the first two cases to be relatively insubstantial, because there is a significant sense in which only the Marvel authorized version (or maybe the authorized version and the fanfic version, but definitely not the dream or private dream journal versions) is about the established character Spider-Woman.

In what sense? In this sense. Imagine that, after the creation of S-WbJ…, a friend of yours reads a new (post-S-WbJ…) Spider-Woman comic and doesn’t understand some subtle plot twist. So you attempt to explain by referring back to how the events in S-WbJ… naturally lead to the plot twist in question. This explanatory move, however, only seems legitimate in the fourth case (or maybe, in special instances, in fan fiction versions of the third option – I think Noah is right that I was oversimplifying various aspects of how fan fiction works). So in the sense of being explanatorily relevant to future authorized installments of the Spider-Woman comic, only the authorized version (and maybe the fanfic version) really tell us anything about Spider-Woman.

Of course, there are other senses in which the dream journal and the dream itself are obviously about Spider-Woman. But it is something like this specialized sense of ‘about’ that I had in mind.

Noah – Those are interesting examples, I was thinking about All-Star Batman and Robin myself. I think all of the cracked list are perfect examples of how a fictional character cannot be harmed in the way Roy is wondering (not arguing) about.

1. Most of the examples listed are more than 70 years old. If there was any harm to the character, I think it would be more apparent by now. If anything, the most widely disseminated versions of the character (the 7 films) include Batman taking lives, including premeditated homicide by remote control.

2. The junkyard “murder” examples don’t really rise to the level of murder. And, as anguished as Batman looks after the garbage truck incident, I doubt that particular story has been referenced since it was published. Inconvenient bits of story line get discarded.

3. ASB&R – I’m sure some aspect of this involves the sanctioned canon vs. unsanctioned canon discussion above, since this series was never intended to be the “real” Batman. But I think it’s also important to note that this version of the character was so different than what had come before, and was so roundly mocked, that there doesn’t seem to be any way for this version to have any impact, much less harmed the “real” Batman.

ummm…

the harm being done isn’t to a MADE UP CHARACTER. this isn’t what caused the controversy.

the harm being done is to women and girls who may want to enter this beloved hobby of ours, see this, and think “this is what *they* think of us…” and never touch a comic again.

come on, now.

Good grief, does anybody read the whole thing? Roy addresses this in the piece! He’s talking about a separate issue because the issue you point to has already been covered extensively in multiple venues.

If we’re dabbling in philosophy, I’d just like to say that asking if a fictional character can be harmed is logically nonsensical, similar to asking if a square can be a circle. The question makes no sense.

The “harm” part of the question implies the character is not fiction, the statement that the character is fictional implies the opposite. The whole line of questioning is a cognitive error.

No…that doesn’t seem right. It’s not nonsensical; everyone knows what Roy’s saying. He’s asking if a fictional character can have moral standing. Those terms are a lot less strictly defined than squares and circles. You can certainly say that the answer is “no” and/or that the question isn’t important, but I don’t see why it’s logically nonsensical.

I,m with Pallas. This:

“The Manara Spider-Woman cover arguably depicts a heretofore good character performing morally objectionable actions”

Yeah, he also loses me. Seems pretty biased and with lots of projecting, some would say. In the representation she is in a high building, so “presenting herself to anyone who cares to look” is kind of far fetched for whats represented there (should say for “anybody with binoculars, satellite surveliance or super vision who cares to watch). Its a bias because the retoric of the writer is meant to be read as the argument, quite literary, instead of articulating towards the argument. It goes further when the writing insists on the character’s behavior as inmoral, as if Rousseu, Kant, Aristotle or himself would know how to judge a woman with spider powers. The writer asumes that she’s climbing to the top of a building at nigth because her motivation is that of exibition; if that was the case, the character and the artist who draw her would have tough of more effective ways to acomplish exibitionism, including one with a present audience (we, as readers, dont count: its about the diegesis acording to the writer of this piece).

And, in the extreme and absurd interpretation that Spider Woman is that of an exibicionist: is that morally reprensible? Really? Showing her naked painted body to the world is more reprensible than the whole paragon of superheores who take justice by their own hands with violent means?

Manara’s Spider Woman problem is a cultural one, not representational. Aparently, Marvel comics readers can’t stand “nudity” nor adult aesthetics, wich would be fine if readers were just teens, but its been long since superhore readers are sophisticated adults with adult opinions at least since Watchmen.

I’ll try to respect any opinions on this, but some people are really pushing it. There have been way more blatant and even despotic use of superheroes representation that have flyed by with nobody sayind a word. When Mark Millar made of Hiroshima and Nagasaki a fictionalized excuse for destroying aliens, a metaphore so cinical about political representation of WW2 (I’d like to see any doing that with Auswicth), nobody raised in arms. In contrast the outrage for this cover is non-sensical; I dont think even teens give a damn.

Adult people who care for fictionalized characters beyond the narrative would do better if they tried to jump of the simulation: characters in fiction are mean for understanding real people near to us, the reader him/herself included. This “morally reprensible” representation of Wonder Woman? Yeah, thats how you interpret the world; God save us all.

He’s not just asking if a fictional character can have moral standing, he’s assumed it when he defines the pre-Manara cover Spider-Woman as a morally “good” character.

*sorry for the typos, it’s kind of hard for me typing all that on the smartphone. Of them all I’ll only beg your pardon for Auswitch.

Speaking for myself, when I mentioned the salient issue, I was only referring to that woman’s comment. I don’t begrudge Roy the right to explore some other side of this issue. But I wouldn’t be so quick to jump all over other commenters who misunderstood the post or especially the comment thread, to which I have *almost* responded “r u high” more than once.

To me the original question seemed to be does this cover somehow sully SW’s character, which I find problematic. Why that cover should occasion a referendum on her moral character is beyond me. But I guess you’re also talking about stealing candy from babies or something? Or Batman murdering people? What? Who?

Rhetorical questions. No need to elaborate on my behalf, seriously. I just think it’s unfair to say that an entire post about SW is not about SW. The commenters (including me) who are picking up on weird panic about SW’s sexuality in the OP are not off-base. “Presenting herself”?? Uh…okay.

I’m not quite sure I understand the arguments being made in the original article, but there’s a common phenomena that’s perhaps a bit like what he’s talking about: The way that remakes or adaptations “ruin” a work.

Whenever a fan-favourite book gets adapted into a movie, there’s always chatter about it now being ruined by the movie. I mean, not about the movie version sucking per se, but the book being hurt by the movie being made. I’ve never quite understood that argument, either, but it’s not an uncommon one.

Even further afield, you have the phenomenon of good records being ruined by a band making a new, horrible album. That one I can understand: The horrible albums Interpol made after the first one made me question whether I was correct about the first one being any good.

@Lars

Way off topic, but as an Interpol late fan (I heard them first around Antics), mostly I find that people (not necesarily you) who detest each new album more than the previous mostly respond to hype, or apropiation of the band instead of genuine apreciation of their music (“they should sound like this or that because they owe me to”). I blame psudo music critics like those in Pitchfork for that (their review for El Pintor is six of eigh paragraps going through the later albums with arbirtray comments about HYPE, not music). At least in the comic book industry Wizard dissapeared long ago now.

Kim — notwithstanding your demurrals about being elaborated to, the reason we went to stealing candy, Batman murdering, etc. was precisely to get around the dubious idea that SW’s character has been sullied, and get to a clearer case for what Roy appeared to have in mind. FWIW.

Roy — I’m afraid we may have got to the stage of argument where all we have left is to thump our fists on the table, but I’ve got two last questions:

1) Like I said, your view seems prima facie crazy, and this thread bears out that I’m not the only one who thinks that. Craziness is fine, but it’s usually motivated by some greater theoretical gain, balanced by something else in our reflective equilibrium. Can you say briefly what that is? Because I haven’t yet seen it, or, if you did say, I must have missed it.

2) Like others, I keep getting stuck on the specific example chosen. Not the idea that the cover shows SW having a bad character — I’m mostly happy to grant that assumption for sake of argument. But the fact that that was the assumption you went to, and that the other example of “harm” in the original post was about writing villains doing non-virtuous things.

These are unusual cases of “harm”, and certainly not anyone’s paradigmatic examples. So my question is whether this is important, or do you think I also harm fictional characters by writing stories in which they stub their toe, whack their head, get shot and paralyzed etc.?

Okay, I’m gonna apologize in advance if any of this is mildly snarky, but (despite Noah being right that perhaps I should have picked a less controversial example), some of the comments at this point are just begging for snark.

Milton: Please read the entire post, and comments, before responding next time. I made it clear that I thought this was a secondary, separate issue raised by the cover (and now raised by other, perhaps clearer, cases we have been discussing). It’s also worth noting that I find the oddly widespread idea that, given a particular controversial incident (such as the SW cover), there can and must be one and only one ‘point’, or ‘issue’ that is legitimate to discuss with respect to that controversial issue to be absolutely bizarre. Surely it’s not hard to understand that a single phenomenon might be interesting (or even worrisome or problematic) for more than one reason?

pallas: If we are dabbling in philosophy, then maybe we shouldn’t merely dabble: There is a huge philosophical literature on whether modally dubious art is prima facie worse art than morally laudable art – I recommend Berys Gaut’s monograph Art, Ethics, and Emotions as a place to start:

http://www.amazon.com/Art-Emotion-Ethics-Berys-Gaut/dp/019957152X/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1411160766&sr=8-2&keywords=berys+gaut

Oh, and before you accuse someone of committing logical nonsense (without providing any argument for that claim, other than a very dubious analogy) it might in your best interest to make sure that the target wasn’t just promoted to full professor of philosophy at an R1 research university, a professor who specializes in (among other things) the aesthetics of popular art and … oh, that’s right, philosophical and mathematical logic.

Gianni: So many things. I’ll just list a few. (1) We already discussed that the original post depends on an interpretation of the cover (and most of us already agreed to focus on other clear examples, so as to avoid controversies regarding what the SW cover actually depicts). But a great many people see the art as unambiguously depicting Spider-Woman in body-paint exposing herself. (2) A lot of people (moral philosophers and otherwise) would agree, I think, that uninvited exhibitionism is morally objectionable. While this might be debatable, its not so obvious that one can merely claim it’s not and be done with it. (3) More to the point: Just because other activities that superheroes routinely engage in might be worse doesn’t make the lesser act okay – after all, the fact that killing someone is worse than kicking them doesn’t make it morally okay to kick. (4) If my suggestion (suggestion, not claim!) that Spider-Woman’s actions on the cover are morally objectionable is right, then this isn’t merely a matter of culture or ‘adult aesthetics’ – its a matter of right and wrong. (5) You’re right, one of the purposes of art (and particularly literature) is to help us reflect on and understand the world around us. But to suggest that as a result, my reading of the Spider-Woman (not Wonder Woman, by the way) cover simplistically reflects some particular world-view is both mildly offensive and indicative of a really impoverished understanding of the complicated manner in which we interpret art and use it to reflect on ourselves and the human condition.

Kim: Apologies. Apparently in the heat of the moment it was as easy to take your earlier comment out of context as it was for others to misunderstand the point of my original post and the question I was actually interested in!

I think this is going to be it for me regarding this post, unless someone – e.g. Jones – post something relevant that actually engages intelligently with the question I was trying to raise, and which I repeatedly made great efforts to clarify, see especially the posts at 9/18, 12:33 PM, 3:25 PM, and 11:11 PM. Reading responses by people who either won’t read the previous comments carefully, or merely want to accuse me of some basic obvious mistake or misunderstanding without providing any reasons for thinking the move in question is, in fact, a mistake or misunderstanding, has gotten a bit tiring.

Jones:

Darn – you went and wrote something that engages intelligently with the original question (see my previous post).

Two quick and simple answers:

(1) The post is really motivated by nothing more than (a) trying to figure out why, exactly, we value art, a traditional, and well-studied, but still very hard, philosophical question, (b) wondering about whether and how the moral values depicted in art connect to the artistic value of the art (the issue discussed in Berys Gaut’s book mentioned above), and (c) wondering whether, if we answer (a) and (b) in certain ways, that we end up having moral obligations of some sort towards fictional characters despite their mere fictionality. So it’s really just trying to figure out a particular aspect of the nature of art.

Of course, you are right – in general if a view is perceived as crazy by most of the people who hear it, then that is a sign that perhaps the view ought to be abandoned unless the view has some other theoretical virtues. But crazy views in the philosophy of art worry me a bit less, since almost any substantial answer to a serious question about the nature of art is going to sound crazy at some level, and out untutored intuitions about art are almost always blatantly wrong when we actually scrutinize them (try explaining where a work of music is located, or what sort of object a work of music is, without sounding nuts).

I chose this example (and have focused on similarly serious ones in the discussion since) because the harm is substantial enough that we care. I suspect that any story that harms a character in any way for no narrative or aesthetic reason is morally faulty in some way (if I am right about a lot of the other points we are discussing), but minor harms done to major characters, or major harms done to minor characters, don’t seem as bad as major harms done to major characters (one thing Gianni got right was that we use fictions to, amongst other things, help us to understand the world, and in ongoing serialized fictions like SW it is the main characters that do most of the heavy lifting in this respect, and hence they are more important in some important sense than minor characters). So I guess the examples reflect the idea that, unlike the case in the real world, some fictional characters are literally more valuable than others. I guess now that I have written this, I am not sure about it, but it doesn’t seem obviously wrong.

At any rate, focusing on major harms to major character seems reasonable, since it will focus things. After all, if I intentionally prick your finger with a sterile needle for no reason, I think I have done something morally wrong (I have in fact harmed you). But the harm done is so minor that no one would likely care much beyond a quick apology (of course, you might avoid me for being weird, but that’s a different issue). If I stab you, however, I have also done something morally wrong in a very similar sense, but the offense is much more severe. I guess I would say that in cases where a writer does harm to a character for no narrative or aesthetic reason, but the harm is minor, then although perhaps the author has done something wrong, it’s so minor that we don’t care, like my pricking you finger with a sterile needle for no reason.

Jones:

Two more quick thoughts:

(1) One reason I focused on the SW example – a reason I lost track of in the ensuring discussion – is that (on my interpretation of her as naked and exhibitionist) she is not being physically harmed, but instead the content of the art damages her moral character: we now have to interpret a previously morally upright character as being less than morally good (again, assuming all the stuff already discussed about whether uninvited exhibitionism is morally bad, etc.) So perhaps there is a narrower (and perhaps more plausible) version of the question I was asking where we focus on only those stories that depict otherwise morally upright characters suddenly doing morally objectionable thing for no apparent narrative or aesthetic reason. Is there something morally wrong with this sort of story, and can we in any substantial sense say that we have harmed the fictional character in writing this sort of story? I am not sure, but if the question in focused in this way it is not immediately obvious to me that the answer is no.

(2) It suddenly struck me that the question I am asking is not really new – it already arose in whole Women-in-Refrigerators debate a few years back. In those cases the debate often took a form that is in some (but not all) ways similar to the sorts of claims I am wondering about here: creators were accused of doing something wrong by killing off female characters merely for the sake of motivating male heroes, and in addition they were often accused of doing something wrong TO the killed-off character in question (e.g. claims of the form “female characters shouldn’t be treated in this manner”). Now, we can still ask questions about how literally we want to take such talk, but, again, it seems at least worth asking whether there in some sense in which we can take such talk at literal, face-value.

OK. This was a fun discussion!

Noah: good grief, sorry.

Roy T. Cook: surely, I apologize for not reading your whole post. also, yeah.