Six miles away from my office is a theater that plays Bollywood movies simultaneously with their Indian release. This is one such film.

***

Holiday: A Soldier Is Never Off Duty

Directed by AR Murugadoss, 2014

***

1.

I first learned of AR Murugadoss in the way most people in the United States learn of AR Murugadoss: he is the writer and director, we are told, of ‘the Bollywood version of Memento.’ Moreover — and this is the important bit, the part that raises eyebrows, because it is about money, and all notions of cultural superiority and/or prevailing taste can generally be cast aside in the U.S. on the proviso that one culture’s lucre is roughly as good as another’s — the Bollywood version of Memento did just as well as the real Memento in global theatrical grosses, and isn’t that something?

It’s true. Memento (2000) carries an estimated worldwide box office take of $39.7 million. Ghajini (2008), its multitudinous crore translated to USD, weighs in at roughly $38.3 million. This remains quite large for an Indian film, but in ’08 it was unprecedented. Know this: while Memento was a small, tricky crime movie made by a near-unknown British director, Ghajini was groomed to be a hit – a massy-classy vehicle for Aamir Khan, one of the most recognizable stars in Bollywood, struck from the proven success of an earlier, Tamil-language film of the same title, which Murugadoss had written and directed in 2005 to splendid response.

One year later, the Salman Khan vehicle Wanted would touch off a lucrative vogue for remakes of “south” films, but Ghajini sat aloof, only ceding its record to Aamir Khan’s next major endeavor, the inspirational comedy 3 Idiots. Its success seemed unique, and Murugadoss was not a straightforward masala man anyway.

Accounts vary as to how Murugadoss came to borrow from Memento, ranging from his having watched the film halfway through writing the script to Ghajini and plunking down its main character in a snap of inspiration, to Jodorowsky’s Dune-like tales of his having merely heard the premise of the English film described to him while concocting the story. Either way, Ghajini is best understood as less a singing, dancing Ballad of Leonard Shelby than a random episode of an imaginary television anthology consisting of nothing but crime stories about people with anterograde amnesia, Memento having served as the pilot.

Personally — as I am wont to do in most circumstances — I tried to ignore the existence of Christopher Nolan to focus on something more interesting. There is a profoundly odd dialectic at work in the Hindi Ghajini. Like the Nolan film, in detailing his story of a man on the hunt for revenge, Murugadoss includes both scenes of ‘present’ action and scenes from the ‘past.’ But there is no tension between b&w and color, and no tricks with the chronology. Instead, all of the ‘past’ footage is shot in a bright, sunny, eminently artifice-driven manner common of Hindi entertainers. A silly Bollywood romance, which ends with the heroine getting bludgeoned to death. It is a memory, horribly preserved; a film by which Aamir Khan’s protagonist might memorialize his happy former life.

The ‘present’ footage, in contrast, is noticeably drabber and dull, with whipping camera movements and ‘gritty’ editing which (to this American) calls to mind network police procedurals. Basically, it is a different kind of entertainment, coexisting in space with its fluffier sibling. At one point, Khan attends a gala function in pursuit of his nemesis, where a stage show is about to begin. He then seems to hallucinate a massive, impossible dance sequence, full of beauty and glamor and costume changes. Normal Bollywood pictures do this all the time, but they merely cut to the dancing, warping the cast into a music video and ignoring reality altogether. Murugadoss, however, implicates diegesis, which I found utterly fascinating – was the director attempting to comment on the psychological salve of candyfloss cinema? Gangs of Wasseypur, a much more self-evidently ‘serious’ project from a ‘serious’ filmmaker (Anurag Kashyap, 2013), would break off syrupy, sentimental songs from older movies and recontextualize them as motivating factors for a criminal antihero; was Ghajini really so different? Hell, would Murugadoss reveal that ‘dark’ stylization might be just as artificial as ‘light,’ pulling the rug out from under the whole vigilante concept? The possibility is delightfully teased!

But this is a tease without climax. Ghajini, in the end, is a pretty common revenge picture, one which entirely fails to answer any of the cinematic questions it raises – if, indeed, it was aware it was raising them.

Clues, perhaps, might be found in Murugadoss’ background. He’d been a writer and an actor during school, his artistic tendencies encouraged by his beloved father, a man of modest means who did not live to witness his son’s success. “AR” were the older man’s initials, folded by Murugadoss with numerological assistance into a lucky pseudonym. Purportedly, Murugadoss also toyed with radical politics in college, though it seems his Naxalite flirtations derived less from a doctrinally Maoist point of view than a generalized concern for social justice. His film school applications were rejected after graduation, so he instead worked as a novelist and story writer while pursuing on-the-job training as an AD, which finally led to his debut as auteur in 2001. He has written every one of his eight directorial ventures. His films have never failed to make money.

When asked once about his success, Murugadoss replied pragmatically: “I am focused; I analyze film trends and work extensively on scripts.” Elsewhere he adds that this is not to copy the latest theatrical successes so much as to understand the tastes of the audience, and hit them with something they haven’t realized they want. He also apparently keeps an eye on foreign concepts; his follow-up to the original, ’05 Ghajini was a Telugu-language picture which took its premise from the notorious sentimental drama Pay It Forward(!!), transformed into a socially conscious action-drama with the amazing title of Stalin. It was then remade in Bollywood under the title Jai Ho, where it grossed over Rs 100 crore, though Murugadoss did not direct; he was too busy with other projects, and no doubt analyzing further trends.

And as I became less ignorant, I wondered: is sophistication a mistake of culture? I saw Ghajini as unusually sensitive and inquisitive re: pop cinema properties, but couldn’t that also be a directness that evades my provincial expectations? In ‘normal’ American films, you expect a steadiness of cinematography, of color correction, so as not to disrupt the illusion of witnessing actual life occurring before you. But since Bollywood films frequently break out into music and dancing anyway, it could be that it makes perfect sense just to ‘code’ the happy scenes as happy, and the serious scenes as serious, in an intuitive visual manner that audiences wouldn’t need to be able to explain in order to know. This way, the maximum number of viewers could interface with a fairly complex plot, as there could be no mistake as to the film’s intent from moment to moment. This is also why Murugadoss, by his own admission, tends to set his films in cities: because they translate better to different languages across India, with little need to worry about anyone puzzling over local customs or obscure dialects.

Analytics. Logic. He’d seem almost a robot, this Murugadoss, if he weren’t so fucking perverse.

***

2.

Holiday: A Soldier Is Never Off Duty, is the newest film written and directed by AR Murugadoss. It is an extremely close remake of his 2012 Tamil-language smash Thuppakki; if you have not been keeping count, know that one quarter of Murugadoss’ directorial oeuvre consists of remakes of films from elsewhere in his catalog, though the filmmaker appears to view “remaking” a film as an opportunity to isolate the flaws of an original and create a perfected version. Holiday, then, can be seen as the final form of Thuppakki. It is not based on any discernible Hollywood antecedent, so I am left to grasp at the trend its analytic creator must have identified.

The answer, I guess, is martial patriotism.

Toward the beginning of this year’s summer blockbuster season, I was advised away from director Gareth Edwards’ new version of Godzilla on the allegation that it engaged in Michael Bay-style military worship. I saw the film anyway, and disagreed. While it is true that the hero of the story is a Navy man, and that Our Armed Forces more-or-less save the day, the American military is nonetheless shown to make dangerous, critical mistakes. They must be saved — as men often are in Godzilla films — from their own hubris.

There is no such vacillation in Holiday; its closest English-language equivalent is 2012’s Act of Valor, a film starring real Navy SEALs and live Navy firepower. Akshay Kumar, about whom I’ve written before, stars as Virat Bakshi of the Indian Army, who is secretly a nigh-unkillable specialist with the Defence Intelligence Agency. He has returned home to Mumbai on leave, where his family plots his arranged marriage with a nice girl, by which I mean a grown adult, but do keep in mind that heroine Sonakshi Sinha *is* young enough to be Kumar’s daughter, and, like a child, is not given a single goddamned thing of substance to do at any point whatsoever.

Even some admirers of this film have suggested it could be even better with the romantic track excised. I suspect, however, that Murugadoss is hedging his bets; the widest audience, after all, may not want to stare at a sausage party, and those with a stake in the promotion of romantic songs will be even less pleased. With Ghajini, a crowd-pleasing romance was built right in to the plot; no such luck here, so best to keep it painless with a familiar jodi – of Sinha’s thirteen film appearances, six have been in Akshay Kumar vehicles, and the two share an easy, convincing chemistry, ideal for mass placation.

And yet!

As with Ghajini, Murugadoss plays the romance and thriller elements of Holiday directly off of one another, this time as deliberate interruptions. In fact, the first 35 or so minutes of the film betray no suggestion that there’s even going to *be* any action – it’s a completely straightforward mismatched couple scenario, complete with a big, ditzy song number where Kumar hilariously and romantically pisses Sinha off by imposing himself on all of her extracurricular interests. This, the film says, is the [h]oliday a soldier can enjoy, but alas, it is short-lived – soon a satchel bomb explodes in a crowded bus, the camera leering at an elderly couple trapped in an adjoining car as they’re enveloped, luxuriously, by flames.

This time, Murugadoss allows no variation in visual approach; everything is shot in a distinctly bright, it’s-gonna-be-okay-the-hero’s-gonna-win type of manner, even as Kumar, having spotted the terrorist behind the bombing escaping with ease from his hospital confines, abducts the man and whisks him away to a bedroom torture chamber, where the hero slices a joint from one of that bastard’s fingers and immediately elicits wholly accurate information. Stow your murmurs, American liberals: not only is torture necessary, it is SO FUCKING COOL.

Before long, Kumar has discovered a pestilence coursing through the blood of India: “sleeper cells,” always pronounced in English, with the frequency and intonation of “LSD” in a ’60s drug film. A talking head on a television fills us in on the details, praising U.S. domestic security policies in the wake of 9/11. This is hardcore shit, quickly lapsing into feverish, ecstatic fantasy. Gathering a group of Army buddies at a wedding reception, Kumar suggests a jolly game for the well-dressed bunch to play. Having kept the original, tortured terrorist dosed on ketamine and locked in a closet for days, Kumar now allows his escape; as would any of us in the same situation, the man immediately and accurately goes about facilitating the complicated, dozen-man bombing mission planned for that date. Men break off from Kumar’s party to follow each new sleeper agent, until it is 12 heroes following 12 villains.

Reach into your bags, Kumar says, and you’ll find I’ve given you a gun! The man you are following is a terrorist! On my signal, you must draw your weapon and shoot him dead in public! Each player agrees without hesitation, and on Kumar’s signal Murugadoss cuts rapidly across one dozen gory headshots, crack crack crack: a coordinated strike on terrorism, just like the coordinated attacks they launch on innocents! Twelve handsome, well-dressed cosmopolitan men — the livelihood of a strapping nation — flee the scene, and the news media immediately and unanimously identifies each and every victim of this ritual as dirty terrorists, causing the leader of the terrorists, played by model-turned-actor Freddy Daruwala, to glower in his well-furnished estate… and summon further terror, via mobile!

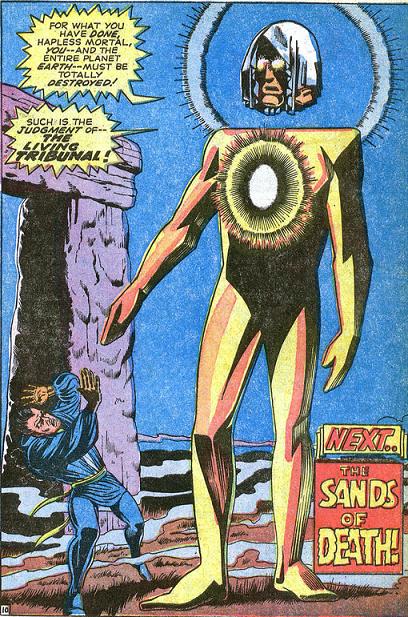

It is too much: a quality that seems to have been discerned by the poster designers, at least (see above). If the writer/director is aware, however, he does not overplay his hand, and lord knows he could. Akshay Kumar is more than capable of playing things five-alarm broad, but here he’s subdued and emphatic. He’s a big improvement over “Vijay,” the preternaturally collegiate star of Thuppakki, sneering his way through every scene like the cockiest freshman in general science and requiring some combination of wirework and intrusively rapid editing to accomplish anything in the way of fighting. Kumar, though 46, is still fit enough to draw from his background in martial arts performance and pull off some genuine stunts, so Murugadoss gladly extends the duration of certain major confrontations to flatter his hero’s proclivities. It makes for rightly perfected action.

There is also an interesting deletion from the Thuppakki version of the story. As I’ve mentioned, both films begin as a sort of feigned romantic comedy, only to abruptly transform into an action-thriller. The romance, however, keeps bumping its way back in to both versions, complete with a ludicrous subplot about Virat’s superior officer becoming engaged to the heroine. In the midst of all this — and so self-evident is the intrusion that Murugadoss at one point has the heroine interrupt a conversation between Virat and a friend about the thriller plot to drag him into the romance track, only for the friend to call Virat on his cell phone near the end of the romance scene to beg him to continue explaining the thriller plot — Thuppakki sees the superior officer try and set Virat up with a sexy lady, only for comedy to ensue when Virat finds out she’s a call girl, with whom no respectable man would ever associate with on a personal or professional level. That’s basically the joke. She’s a nice lady, but she’s trash.

This bit is absent from Holiday. Possibly, Murugadoss felt it detracted from the pacing, but then again – he does plan to work with Sinha further, this time as solo star on a Hindi-original project, an untitled 2015 action movie “based on a story which is close to my heart and has a very personal and powerful message for all Indian women.” Might he now sense the trends shifting?

Holiday otherwise remains comprehensively patriarchal, both in terms of how it approaches women, and how it approaches military protection. Kumar gets quite a lot of people killed due to retributive violence over the course of this film, but it’s all collateral damage. At one point he even manipulates his own sister to be kidnapped and nearly murdered by terrorists, just so he can track ’em down, shoot ’em up, and lock the lone survivor in the boot of a commandeered vehicle. The girl castigates her brother’s lack of compassion on the ride back, only for Kumar to shut her down in borderline Marine Todd fashion by declaring that if terrorists are willing to die in their mission to kill thousands, civilians ought to be ready to pay the same price as the soldiers and police who gladly face death to protect them. BOOM.

The girl then informs her brother that he’s not yet killed all of the terrorists, which does not so much challenge the statements made as segue into another round of enhanced interrogation (SO COOL), only for the romantic track as personified by Sonakshi Sinha to scale a ladder a la Clarissa Explains It All and surprise her man inside his bedroom/torture chamber. Kumar manages to hide the prisoner in a closet, only for someone else to approach the bedroom door; thinking it’s his mother, Kumar then shoves Sinha in another closet, only for the second intruder to reveal himself as a policeman friend. A relieved Kumar opens up all the closets. “Don’t you keep any clothes in there?” asks the friend.

Then there is a romantic song sequence, and immediately after we see that Kumar has tortured his prisoner to death and dumped his corpse in public. Perhaps he did it in the ‘real’ world, while the romantic daydream played. The news identifies the dead man as a terrorist; there is no dissent.

At this point, you’re probably wondering what the sleeper cells are hoping to accomplish. I’ve watched two extremely similar versions of this movie in two languages, and I’m still not 100% sure on that myself, but from what I can gather there’s a bit of a twist involved. The terrorists, it seems, are at the beck and call not of religious zealots or foreign nations, but certain factions of the Indian government itself, hoping to extract prestige and wealth from scaring the population into trusting them, then playing the hero as the pre-planned attacks stop. Only the Indian Army is pure of sleeper cell contamination.

I like this scheme. It brings us right back to Murugadoss the would-be Naxalite – “empowered with arms,” he said, “to fight for the masses.” Think like an analyst: who is more *acceptably* armed than the Indian Army? And it isn’t a novelty to have them cleaning up the government at large; there, Murugadoss is drawing from the library of his great role model, Tamil pop cinema icon Shanmugam Shankar, who — before whipping up a frenzy of computer graphics at the helm of mega-blockbuster Enthiran — created popular vigilante films in which men who can’t take it anymore enact lurid expressions of popular disenchantment with widespread corruption. In Bollywood, this sort of thing arguably goes back to the ‘angry young man’ persona of superstar Amitabh Bachchan in the 1970s. Massy hits are lousy with crooked cops, dirty politicians, avaricious bureaucrats – positioning those scumbags as the power behind the sleeper cells isn’t radical, it’s logical.

And as we’ve already established, AR Murugadoss is a very logical man, both in terms of popular calculation and the raw nerve appeal of vulgar poetic vengeance.

There’s a scene leading into the climax of Holiday where Freddy Daruwala, model-hot terrorist kingpin, phones Akshay Kumar with a nasty surprise. A bomb has been hidden in a mall, where one of the 12 assassins has taken his whole family, and it will explode in ten seconds! Frantic, Kumar phones his buddy, and urges him to take his wife and kids and flee the premises, but the man becomes paralyzed considering all the people he’d want to save. He and the camera, and therefore we, stare into the eyes of happy children, one after another… until a blast rips down the walls!

Anything is justified in the face of this. Never mind that Kumar arguably sort of provoked this response – anything is justified in the face of this. We might even imagine a quiet respect, underneath the agony, for the screenwriting utility of this grandest of gestures. From this sacrifice — small, really, when you consider the safety of a nation’s people! — the hero is beaming and uncomplicated again, like pressed linen or a polished gun. Murugadoss knows.

In seconds, the hero will be addressing an audience of army officers – all of them confined to wheelchairs. They will be reactivated for one last mission: to mold plastic explosives with their own hands, so wizened with sacrifice. Imagine: a suicide bombing on the terrorist leader! A taste of their own medicine at last! The audience of crippled veterans applauds with passion. Murugadoss knows. Audiences in cinemas across the globe are cheering too.

Every one of us knows.

You needn’t conduct a survey to get the consensus on that.