After a year in New York City, where the claustrophobia was so oppressive that I sometimes snuck out into the hallway to beat on the plywood screwed onto the roof hatch, my husband and I moved to a small village in Ohio. Yellow Springs is a town you may have heard of, in spite of its population of only a few thousand; the hometown of Dave Chappelle, a liberal enclave filled with older radicals and young free-spirit entrepreneurs, it is bounded by farms and parks. The Tecumseh Land Trust, a sort of demilitarized zone whose maintenance keeps strip malls and chain stores at bay, insures a level of charm annihilated by an influx of big box stores in neighboring towns. It is bounded on another side by Glen Helen, a small nature preserve with winding trails leading over a waterfall and a modest center for the rehabilitation of injured birds of prey. Our downtown consists of a few restaurants, a few coffee joints, a number of shops devoted to the functional and ornamental artwork of locals, a movie theater, and a local grocery. On Saturdays, much of the town turns out for the farmer’s market, populated by piles of organic peppers and tomatoes, small-batch fermented vegetables, and cheese from the cows I walk past on foggy mornings.

A year after our move, the pavement was still hot against the soles of our feet as my husband and I stood, arms around one another’s shoulders, looking far down the street. This was an awkward posture for us—neither a cold nor an overly affectionate couple—and after a while, we ended up standing apart but close, as the rattle of gun shots down the block shuddered through the air.

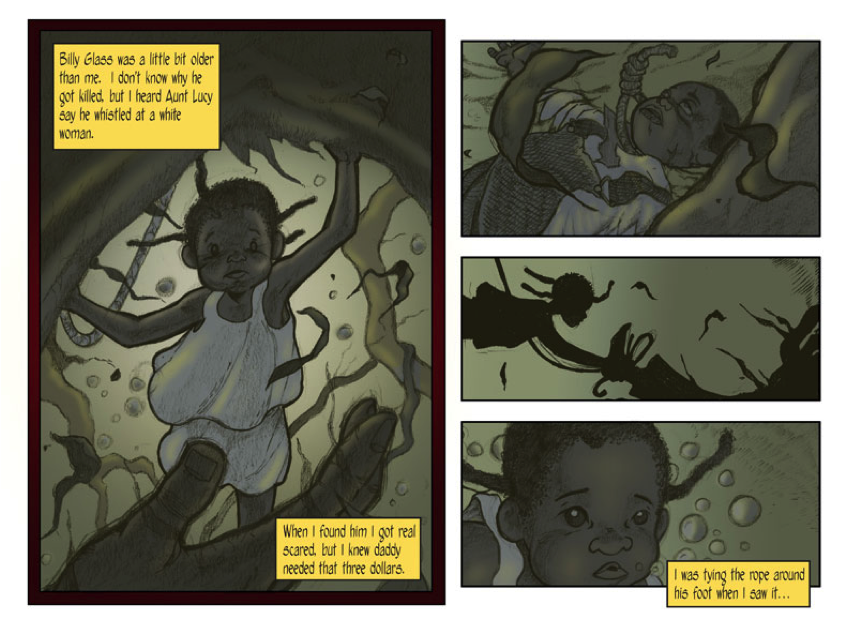

I came from a neighborhood where SWAT raids, random gunfire, and despair were not uncommon. I was in eighth grade when a girl in my class was gunned down in a nearby parking lot—I didn’t know it was her, but I had seen a body lying in a parking lot on a walk. One morning, I woke to the train whistle, more insistent than usual. A block away, a man had simply sat down on the tracks and waited. The rails were awash in blood by the time I was going to school, a fine spray over the rocks in the cess. A stray bullet fired by a neighbor in a fury of celebration one July 4th afternoon lodged itself in the wall above my parents’ bed. If it had been the evening, it would have penetrated my father’s abdomen. He dug it out of the wall and displayed it next to the pennies he and my mother crush on the train tracks.

On this night, however, violence was out of place.

The gun battle was raging at 11pm on a Tuesday. After picking Ian up from work when the sirens began wheeling around our neighborhood, we padded back and forth between the porch and the intersection between our street and a major road. For two blocks beyond the intersection, police cars lined either side of the street, and the main road was rapidly filling with news cameras, giant lights casting a surreal glow on the corner I normally turned to walk past a friend’s wild flower-strewn front garden. She sometimes punctuates the arboreal splendor with artfully curated holiday decorations. The pavement was still hot against the soles of our feet as Ian and I stood, arms around one another’s shoulders, looking far down the street. This was an awkward posture for us—neither a cold nor an overly affectionate couple—and after a while, we stood apart but close, as the rattle of gun shots down the block shuddered through the air.

Facebook had exploded with rumors two hours before, but by 11pm, we know that the shooter was Ian’s friend Paul, that he was barricaded in his house a few blocks north on our street, and that he would not be coming over for dinner on Wednesday.

We had been trying to find time for a cookout for a year, in part because I had never met him in person. Online, Paul’s regular posts on Ian’s Facebook wall, while littered with extraneous ellipses, were well-reasoned, and emotionally raw—a mockery of form that nonetheless commanded respect for their naked subjective engagement. In spite of this, however, he was not known for his delicacy of approach. Debates about guns were particularly vituperative. Paul had, several years before, been the subject of a raid, which turned up hundreds of guns and thousands of rounds of ammunition. All of it was legally purchased, and all of it was returned. Several other friends had already blocked him, and his rambling responses were occasionally aggressive. Unlike those on most internet commenting threads, however, the longer Paul interacted, the sweeter he became—after what began as a particularly vicious battle, the thread would eventually devolve into Paul’s declarations of love and appreciation, grateful for the debate.

Ian had seen him the day before, Monday, at Kroger, and was a bit sad and distant after watching Paul limp to the plastic pharmacy counter to collect his blood pressure medication. He had picked me up from mucking out stalls, I was flush with the new strength in my arms, and reeked of dirt and manure, my spine singing from the muscles knitting and thickening across my shoulders and back, and easily gamboled over Ian’s ache for Paul’s reduction.

Tuesday morning was spent pulling meat out of the freezer to defrost and marinate.

My fingers closed on Ian’s arm as we counted seventeen shots in rapid succession. We walked back to the corner, looked down at the army surrounding Paul’s small house, briefly embraced, walked back.

On Wednesday morning, I started to weep.

A week before, the day after I defended my dissertation, my friend Jeremy was gunned down in a local bar after what can only be described as a psychotic break. During high school, Jeremy’s parents’ porch was a safe space; conveniently placed alongside of a main drag, but tucked just away off on a side street, the wide, concrete steps could accommodate more than a dozen milling youth, while the solid stone paling shielded us from passersby. Teenaged girlfriends and I loitered while he and his friends joked around, but the unusual element in this scene was that Jeremy and his friend Phil policed the discourse; it was a misogyny-free zone, the only anodyne social space in my adolescence.

Jeremy and I had been in irregular but enthusiastic contact since we were in high school, using the innovations of digital correspondence to manufacture political debates every few months. Looking back on a long conversation on hate crimes, I’m struck more by the pleasantness of the exchange than by our stark disagreement. Jeremy thought that the existence of the legal designation of hate crimes amounted to criminalizing thought, while I see them as a classification of a crime committed against an individual but intended to terrorize a larger group. Jeremy thought profiling could be useful, while I think that profiling is an act of racism. These are wide gulfs in thought and approach, but his respect for my views was apparent in his phrasing. He wasn’t seeking to convert me—merely to show me that his point-of-view was reasonable. I often explain to my students that this is the only truly honorable approach in a debate.

On the day of his death, according to reports, he argued with his mother before departing her home. When confronted by police he removed his gun from its holster and waved it around in a threatening manner, at which point he was repeatedly tased and then shot to death in a bar around the corner from his parents’ house, the only bar in crawling distance from my apartment of half a decade. He had apparently tried to raise his gun as officers struggled him to the ground.

It has been nearly two years since their deaths, and I have fought with myself over how to say something meaningful about them. Mass shootings are in the news more often than not, and each time another young man murders, I think back to Paul and Jeremy. Their stories are not unfamiliar: both had issues with mental illness, both had easy access to firearms, and both had a deep and abiding suspicion that gun regulation was the first step down the road towards fascism. But both were also deeply compassionate, vulnerable, had families they loved and large social circles. They were friendly and warm, and when they talked about the issues they cared about, they spoke clearly and calmly, and they listened respectfully to other views. It won’t do to memorialize them with another call to fund mental health services, to regulate the sale of firearms, or to expand government oversight. They had good access to mental healthcare, they purchased firearms within the bounds of the law, and they would have been appalled if I leveraged their memories for more regulation. It won’t do to call on neighbors and friends, or to point towards a particular viewpoint or conspiracy theory. They had friends and family who cared deeply, and they weren’t rigid ideologues. They were nuanced.

In both cases, the authorities tasked with handling Jeremy and Paul’s respective outbursts were in danger, but also were both heavy-handed, which led to discussions in Cincinnati and Yellow Springs about the increasing militarization of the police force. It’s a discussion that should continue, but it is not the only discussion worth having in relation to outbreaks of gun violence (if their perpetuity can even be captured by the term “outbreak” anymore).

These deaths recall for me a darker aspect of our culture. As I mentioned at the opening of this essay, I’m not a stranger to violence. The neighborhood I grew up in goes through regular cycles, the ebb and flow of blood that is a fact of life in poverty. As a teenager, I had guns trained on me by both criminals and officers, and never in the context of a “drug deal gone wrong” or during an arrest. Instead, it was during activities remarkable in this context only for their dailiness; walking home from getting a cone of shaved ice, walking into my parents’ back yard. When the ATF raided the house two doors down and pulled 147 illegal guns out of one side of the duplex, kids had been playing in the front yard an hour before. The girl in my 8th grade class who was shot to death in a parking lot two blocks away. Shots fired were nothing irregular. These were not the experiences of the vast majority of my white classmates, whose houses were nestled in quiet cul-de-sacs in different neighborhoods that seemed very, very far away.

But now, the boundaries are failing. It isn’t that mass shootings are becoming more frequent. It’s that they’re becoming more frequent in ways middle-class white people can see. At 33, now a middle-class white person myself, it is eerie to watch the type of violence I grew up understanding to be common follow me into areas where the police brutality, the S.W.A.T. raids, the tanks, the guns, and all of the other attendant material hallmarks are clearly perceived as something new.

One of the things that always bothered me in discussions about gun violence and violence in general is that those who have not grown up in the shadow of its threat often assume that we acclimate ourselves to it. Environments of violence don’t breed an adjustment period that is capped with a reconciliation with one’s surroundings. It doesn’t get less traumatic just because it happens every day.

I’m a professor of English now. My work is concerned with the representation of violence in literature and the study of empathy. The longer I consider the questions that have guided my life and career, the less I believe that empathy exists beyond a very narrow engagement with the people around me who are like me. Who are around you, who are like you. I worry sometimes that my academic interests are turning me into a sort of voyeur sociopath, who has feelings but suspects that they are considerably more limited and less useful than most would assume. As I read over the essays written by smart, caring people attempting to grapple with this suddenly more unsafe world, I think back to the neighborhood of my youth, where if you chalked the outline of every body that had lain on those streets, you couldn’t take a step without toeing the outline of another tragedy.

The last discussion I had with Jeremy centered on gun control, gun rights, and intent versus contemporary usage in Constitutional rights. While he advocated for gun rights, he was nonetheless disturbed when I sent him information about the connection between the ratification of the Second Amendment and Virginia’s slave-hunting militias. He had a conceal-and-carry license, and frequently encouraged me to buy a gun and take classes in order to better protect myself. In one of our last exchanges, he told me that he wanted to be “the good guy with a gun,” and that he hoped, in spite of my views, I would thank him. Winky face.

I can’t help but wonder, as I re-read those messages, whether a relentless consciousness of the chaos at the gates was what compelled him to have that gun, and if a more immersive vision of it—as I had in my old neighborhood—would have made him feel any differently. But I don’t get to ask him, which is itself a tragedy, because he would have had some interesting thoughts to share.