This first ran on Splice Today.

_________________

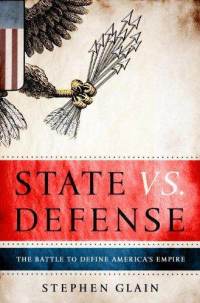

Stephen Glain’s State vs. Defense is a chronicle of America’s post-World War II militarization of foreign policy. Which is to say, it’s a long, depressing slog through stupidity, stubbornness, waste and blood. From Joe McCarthy’s bone-headed, politicized assault on civilian China experts in the State Department to Jesse Helms’ bone-headed, politicized assault on civilian foreign experts of all sorts; from the fictitious Gulf of Tonkin incident to the fictitious WMD’s in Iraq; from the groundless characterization of the Soviets as an aggressive threat during the Cold War to the groundless characterization of China as an aggressive threat today, the United States has for six decades picked up bucket after bucket of bullshit, buried its collective head in the offal and gone staggering blindly off towards empire. At some points in the accounting, you’re forced to wonder why Washington even bothers to invest in weapons. Why not, after all, simply cut out all the middlemen and just physically bury our foes, real and imaginary, in trillions of dollar bills? At least it’s a more effective strategy than SDI.

Stephen Glain’s State vs. Defense is a chronicle of America’s post-World War II militarization of foreign policy. Which is to say, it’s a long, depressing slog through stupidity, stubbornness, waste and blood. From Joe McCarthy’s bone-headed, politicized assault on civilian China experts in the State Department to Jesse Helms’ bone-headed, politicized assault on civilian foreign experts of all sorts; from the fictitious Gulf of Tonkin incident to the fictitious WMD’s in Iraq; from the groundless characterization of the Soviets as an aggressive threat during the Cold War to the groundless characterization of China as an aggressive threat today, the United States has for six decades picked up bucket after bucket of bullshit, buried its collective head in the offal and gone staggering blindly off towards empire. At some points in the accounting, you’re forced to wonder why Washington even bothers to invest in weapons. Why not, after all, simply cut out all the middlemen and just physically bury our foes, real and imaginary, in trillions of dollar bills? At least it’s a more effective strategy than SDI.

SDI is still under development, of course, at least as far as I could figure out from the Internet. We also, as Glain notes, continue to have troops in South Korea, “defending…one of the world’s most prosperous countries from its famine-stricken neighbor,” as well as troops wandering around the Sinai Desert “as they had since 1982 as part of a multinational peace-keeping force.” When the Cold War ended and we didn’t have any reason to gratuitously and provocatively violate Soviet airspace with spy planes, the military brass, reluctant to end a program just because it was useless and dangerous, decided to start gratuitously and provocatively violating Chinese airspace. This has resulted in a heightening of tensions that could conceivably, Glain notes rather helplessly, lead to a catastrophic Sino-American war.

Indeed, the overwhelming takeaway from Glain’s book is helplessness. No matter the cost in American lives (to say nothing, of course, of those poor bastards overseas), no matter the cost to our standard of living, no matter the catastrophic foreign policy failures, the empire, it seems, only expands. Even Commanders-in-Chief, in Glain’s account, can do little to stem the inevitable American march towards war. Glain, for example, points out that president after president has been horrified by SIOP, the Pentagon’s Single Integrated Operational Plan for “winning” a nuclear war. In the first incarnation of the plan during the 1950s, “Casualty estimates ranged between 175 million and 285 million Russian and Chinese dead, regardless of whether or not China was party to a Soviet attack [Glain’s emphasis]”. Counting dead in Eastern Europe and resulting fires, the death toll would probably have topped one billion. Eisenhower said the plan “frightene(ed) the devil out of me,”—yet he signed off on it. Kennedy wanted to get rid of it too, but didn’t. Reagan—not a man noted for his soft stand on Communism or, indeed, for his rationality—called SIOP “crazy.” Yet, despite the fact that president after president has condemned it, and despite the fact that the Cold War has been over for more than two decades, SIOP still exists, a sign of America’s apparently insatiable nostalgia for apocalypse.

Glain is excellent at explaining bureaucratic infighting. In one passage he discusses how a supine Condoleezza Rice as Secretary of State failed to back her wonks, with the result that the invasion went ahead without any input from anyone who had any clue about Iraq before the invasion. In another he describes how the oleaginous Richard Perle helped undermine massive arms reduction at the end of the Cold War by encouraging Reagan’s woozy fantasies about the viability of SDI.

Still, Glain’s focus on the upper echelons of policy tends to leave a few questions unanswered. Kennedy and Johnson, Glain shows fairly clearly, didn’t want to escalate in Vietnam, but they did, in large part because they feared political backlash. Obama and Biden made some vague gestures towards attempting a drawdown in Afghanistan, but they were, according to Glain, politically outmaneuvered by their military officers. “For Obama,” Glain says, “there was no alternative to expanding the war, particularly if he wanted to win at least some Republican support for his domestic agenda.”

The question, then, becomes not so much why do presidents want to engage in endless military overseas adventures, but rather, why do we? Despite war after war; despite a humiliating, catastrophic failure in Iraq; despite what appears to be an endless slog in Afghanistan; the American people just can’t say no. Sure, there have been occasional protests; Glain points in particular to the nuclear freeze movement in the 1980s which arguably had a real impact on Reagan’s foreign policy. But in general, and especially since 9/11, we seem as a whole in love with our empire. What is our problem?

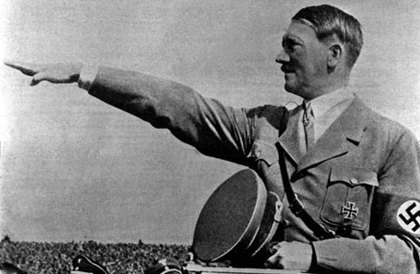

I don’t have a definite answer, but I have a guess. Our problem is that we are cowardly, craven shitheads, who spend our lives in desperate fear for our measly, worthless lives. We drop bombs on the innocent and guilty alike, kidnap, torture, and assassinate, and plan to wipe all human life off the earth because we are terrified that somebody might try to kill us.

Don’t get me wrong. I really don’t want to die in a terrorist attack. I am even less eager to have my loved ones die in a terrorist attack. But at some point, you really do need to buck the fuck up. The chances of me or anyone I know getting killed by murderous strangers is infinitely smaller than the chance that I’ll die in a car accident. And it is dishonorable to allow my government to drop bombs on Afghan wedding parties on the off chance that I might possibly be slightly safer. How many people, exactly, need to be reduced to jelly to make up for Americans’ collective spinelessness?

The Right likes to wail about the culture of dependency fostered when you provide some minimal resources to prevent people starving in the street. But nobody wants to talk about the real culture of dependency; the trillions of dollars we spend on our defensive nanny state, assuaging our knee-jerk timidity by swaddling ourselves in weapons of death. Our leaders like to talk about American virtue, but there is no virtue without personal courage. Until we realize that, our terror will continue to be a scourge, and the only question will be whether it will destroy us before, or along with, the rest of the earth.