I knew I’d seen the actress who played Oracle (and who I blame for sucking me into watching this damn travesty of a television show, curse it) before, so I checked Wikipedia, because that slightly off nose and those cheekbones were familiar. Ayup. Bats. (Look, I went with a friend who adored cheesy horror and it had Lou Diamond Phillips–don’t judge, OK? Also, it wasn’t that bad. Now you can judge.) Also, the Mentalist, where she was killed off.

So, as astute readers might know, I’ve got a bad leg, so I’m not the spry, handstand performing Vom of ages past (and yes, actually, my usual workouts did involve handstands, no joke). Nowadays, I walk with a limp and sometimes use a cane, so a superhero who is stuck in a wheelchair appealed to me, especially if she was brilliant, lead a double-life, had a Greek inspired name, and kicked butt. We all have our ids.

Now, I’d heard this show was pretty bad. But lots of people hate comics TV on general principal and it garnered a lot of viewers before being inexplicably wiped off the air. So I thought maybe it was just the usual insular bitching and moaning about continuity or whatever.

Ahahahaha. No.

This show is truly, deeply, wretchedly bad. Which is a shame, because it had so much potential.

I’ll admit upfront that I only made it through the pilot. Maybe things get drastically better, but I doubt it.

So, we begin with Alfred narrating a tale of Gotham and talking about Batman and Joker, which kind of annoyed me, because I am not watching this show to find out about Batman. But anyway. So Alfred says that Le Bat put away the Joker, but first, the Joker took his revenge by cruelly killing or maiming the ones Batman loved. We watch Catwoman get stabbed while her daughter watches on (secret lovechild of the Bat and the Cat!) and then Batgirl get shot after a weirdly gratuitous shower scene (I don’t know, because this show was supposed to be for women, I thought) and then we see that a little blonde girl gets visions of all of this.

And OK, none of that sounds bad, actually. It sounds like a comic made into TV, sure, but not bad. It gets bad when we watch the young girl, now a teenager, meet a guy on the bus as she goes to Gotham city to make her fortune. That’s when the cliches start–because he asks her if she’s running from or to and she ends up taking his number and I just rolled my eyes. I don’t know who the hell writes this shit, but every girl I know is wary of strange guys on buses who sit down next to them and start chatting, cute or not. I mean, lol whut. It’s eventually revealed that the guy isn’t so nice afterall. What a surprise. I never saw that coming.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. So, the girl on the bus is the teenaged Dinah, and she’s looking for two women she’s seen in her mind but never met.

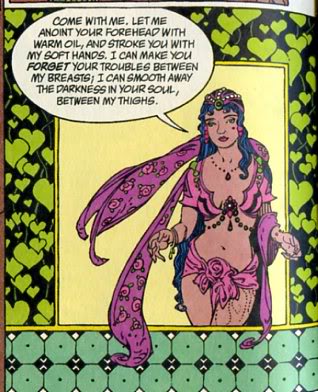

Meanwhile, we get to see Helena, Huntress, swank around in the most absurd outfit for crime fighting I have ever seen. It’s like a bizarre combination of floaty fairy-wing and dominatrix, and it just does not work for me. There’s a weird wide-neck nearly-disco collar but the fabric is gossamer and there’s pleather or something and just….

Huntress is beautiful and cranky and athletic and she’s kicking and fighting and beating up bad guys in dark alleys and yet somehow instead of being enthralled, I’m thinking, gosh, I bet that’s really uncomfortable to workout in. I hope she’s wearing proper support.

….This is probably not the emotion that the producers were hoping for.

I know it’s cool and all, but my goodness, that would get jabby into uncomfortable places and how could she bend properly to do roundhouses? I kind of want to hand her a Title9 catalog and recommend she look into something made from breathable fabrics and maybe some better cushioned shoes. Nikes, perhaps, or with all that leaping, maybe some Rykas.

If you think I’m overthinking things in an action show, it’s probably because the editing in this fiasco sucks. There are long pauses between words. There’s time for people to strike ridiculous poses and then just….stand there. It’s kind of weird and sad and I wanted it to stop, because at the heart, there’s some interesting possibilities for storytelling.

The three women eventually come together in a loft with nifty gadgetry (although the head scanner looked a lot like a McGuyver’d cuisinart container, which made me giggle). Anyway. Three women, all from rough pasts, making a little family and happiness and fighting crime.

Which would be awesome, except there were all these plot holes. The docks at Gotham city have been bought up and haven’t been used. No one’s been there for years. Dun dun dun. Really? No one’s been at the docks in a river-based city? Really?

Huntress goes to visit a businessman wearing her dominatrix “work” getup. She looks like a very weird, expensive hooker, but this is what she wears when fighting crime, I guess. They’ve got goggles that mockup vision miles away but nobody’s thought of undercover business casual, I guess.

It’s just very puzzling.

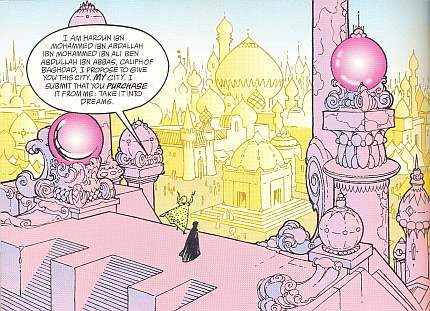

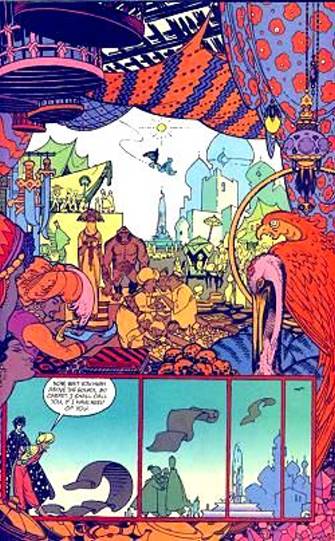

The villain in the pilot is painfully obvious, and the way the three women battle him is just as obvious. There’s a moment that should be touching and emotional, when in her mind, Batgirl/Oracle has legs in the villainous dreamworld and then gets crushed down to her new body with no working legs, but it just came off as flat and kind of embarrassing.

And in the bat-leather costume, Batgirl just looked kind of weird. Not confident and awesome, but, dare I say it, silly.

Which is really the whole problem with this show. In Star Trek, costume silliness is everywhere. It’s as if 100% lycra was the perfectly normal and valid lifestyle choice of the future. Only a few people get into funny looking threads and those few are aliens. The bland Star Trek sets are kind of like community theater. You’re not supposed to notice them.

In Birds of Prey, the whole set-up is backwards. Most people, extras and Dinah and Oracle at her dayjob, are all picture-perfect and real as real. The ones who aren’t real are Huntress, Batgirl, and any villain we’re supposed to take seriously, like the Joker. And I’m sorry, but it just doesn’t work. Joker doesn’t look scary. He looks like my neighbor kid got into the cheap Halloween greasepaint again. It’s comical, and not in the echoes the fine world of graphic novels sort of way.

Much like any TV, good storytelling would have carried the show through bad costume, silly sets, and ridiculous special effects. I’m sorry to say that it’s just not here. So much potential, so many cool characters, and….we get cliches and some heavy-handed acting.