Caro keeps writing these massive comments that I hate to see buried in the threads. So I thought I’d highlight this one too. (I’d urge people to click over to the thread also, though. James Romberger, Robert Stanley Martin, Jeet Heer, and others also have many interesting thoughts.)

____________

Gracious! I couldn’t participate yesterday or Friday and it’s going to take me awhile to really catch up, but I think I need to jump into the James/Robert kerfuffle here because I think James’ real target is probably me. So I’ll try to clarify.

For me it is a question not of giving precedence in the creative process to one person or another, or even to one skillset or another, but just of teasing out all the different “crafts” that go into making a really extraordinary comic. The importance of visual craft is certainly indisputable. I mean no dismissal of it. But I think the craft of manipulating narrative is also very important, and — depending on the conception of the work — the craft of manipulating prose may also be important.

So the question for me isn’t which is more important, because I think that there is no right answer to that — creators can make choices about whether to try and balance them or let one be dominant on a case-by-case basis. That’s part of the craft of creating any work, choosing which elements to emphasize at which point.

But I also do think it is the case that, de facto, right now, advanced visual craft is consistently and significantly much more important to people in art comics — both creators and fans — than advanced narrative craft, even though some creators dismiss both. At the level of skill, James, as you rightly point out here and many other places, it is extremely difficult to find someone who is really gifted at both visual creation and narrative manipulation. The conditions for getting highly skilled at visual craft are more accessible to cartoonists than the conditions for getting highly skilled at narrative craft.

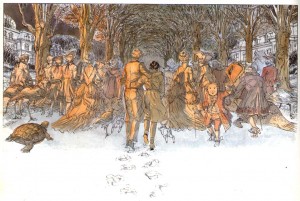

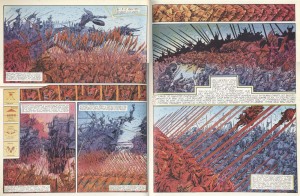

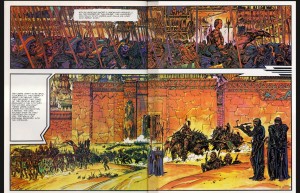

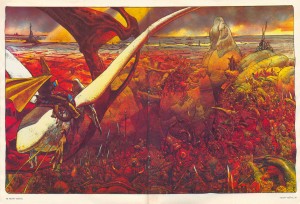

We’ve discussed this before: there are so many inputs to that — education, culture, aesthetic preference, history of the art forms — it’s just really rare that people are first-rate at both. Although I can make arguments for people here and there, I really can’t come up with anybody working right now other than Eddie Campbell who I think sails easily over my bar, except possibly Dan Clowes, who still isn’t quite in Campbell’s league narratively.

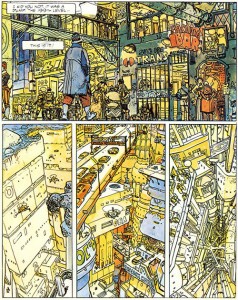

Given that difficulty of finding people who are good at both, and given the pressures of a commercial work environment, I think it’s logical that there aren’t many (any?) mainstream collaborations that have the seamlessness, the balance between the different craft inputs, of a tremendous literary/art comic like “Fate of the Artist.” I do understand what Gary and Brunetti are getting at with the notion that a single creator can integrate the disparate crafts in a way that’s very difficult for collaborators. A really seamless artistic collaboration probably requires a meaningful level of intimacy and honesty that seems likely hard to get in a really commercial environment.

I do understand the struggle here over who can and should get credit — without that intimacy and honesty, the more aggressive personality is probably going to be in the lead. But I think credit is a red herring when talking about issues of approach, because who gets credit would depend on how the approach played out in the specific work. Credit is specific; approach is general. I don’t think any particular imbalance is an inherent property of collaboration — look at John and Sondra of Metaphrog. I don’t have the sense that one of them is more “in charge” than the other. I think they are true collaborators. But that’s not going to be the case with all collaborators. They, like a lot of bands, get around the issue by giving themselves a collective name and emphasizing the group work.

I think it’s essential, therefore, that we bracket questions of credit and the relative importance of individual contributors when we think about the value and risks of collaboration in general. I think we need to look at the actual effects of the Gary/Brunetti approach in practice, not just the romance of it as an ideal goal: what so often happens in single-creator comics is that the elements of “architecture” typically associated with writing, the manipulation of narrative and the rudiments of fiction that Barth calls “craft”, get short shrift — often relative even to film and mainstream fiction, but especially relative to the types of narrative manipulation you see in the most ambitious prose writing.

This is partly because, I think, many cartoonists simply aren’t aware of how craft-intensive the manipulation of narrative is, or they think, like Dan says for Lynda Barry, that narrative is and should be something we do “naturally.”

Up to a point, the notion that human beings are storytelling creatures is true, with some caveats to what “natural” means, but narrative-minded Western humans have been stylizing that “natural” ability for at least a few hundred years now, so it’s a pretty aggressive choice to reject everything they’ve done out of hand. Not that you were defending that stance, James, but to privilege “naif” writing is to be extremely aggressively anti-writing, at least in the sense of what “writing” means to most people who spend a lot of time reading prose fiction.

I think Barry’s anti-Craft stance is much, much, much more harshly against writing than Robert’s is against visual art. I find it really hard not to get very personally offended at it, and the only reason I can avoid it is because it seems to have a psychological source rather than a political one. She feels excluded by formal writing, and so her response is to construct a pedagogy that excludes formal writing right back. That’s not personal against me. But I just don’t agree that either group needs to exclude the other, and I think she’s wrong to approach it that way.

This quote is a good place to expand on that point:

ask her about how she wrote CRUDDY and she’ll tell you a tale of years of woe stemming from reading book after book on story structure and novel-writing, which ended only when she threw it all away and painted the novel in ten months with a brush.

I’d be curious to hear Dan’s response to Noah’s form/content point, but my problem with this ties back into the Dickey book and the tangent with Charles about reading speed – you don’t develop intuition about story structure and novel-writing by reading how-to books. You develop intuition about story structure and novel writing by reading thousands of novels. How-to books just help make you more conscious of things you already know about and have experienced through tens of thousands of hours of reading prose books. Those how-to books resonate and make sense not because they show you something new, but because they articulate intuitions you already have as a reader. If you don’t have those intuitions already developed through that relationship with reading, those books won’t make sense. They won’t tie back into anything “natural” and they’ll feel horrifically artificial, like they are talking to someone completely different from you.

And if you don’t have that intuition, it’s going to be very hard to manipulate narratives and write in ways that speak intimately and in compelling ways to the people who have read thousands of novels. Those people SHOULD BE an audience for “literary” comics. But we often are not, because there is such widespread contempt for the writing we love among the comics community. It is a fierce exclusion, and one that feels very deeply personal. And it is a completely unnecessary exclusion — and I think often a completely UNINTENTIONAL exclusion, born of psychology and lack of experience and interest rather than actual dislike.

So although I want to qualify again that as a way of getting at inner process, Barry’s pedagogy sounds extraordinary, what I find so terribly off-putting about it, at least as presented here, is her seeming inability to see past the limitations of her own, “naif” or “brut” discourse to recognize how her pedagogy and its goals could work with rather than against more craft-intensive approaches to writing and more stylized approaches to narrative, how it could be welcoming to prose readers rather than exclusive of them.

There is no reason why comics cannot have both a brut, naif tradition and a full-range of more stylized traditions in narrative — the exact same way it draws from both naif and stylized traditions from visual art. There are brut visual traditions as well as artists who are as skilled as the best classical illustrators and painters, and comics welcomes them all.

But for writers, if you are interested in more stylized narratives, or in more academic ways of talking about and thinking about narrative, you are consistently marginalized — forced to defend your perspective against charges that it’s “anti-visual” or anti-artist, and, more aggressively, told you are insensitive to the history of comics or just plain uninformed. That type of assertion, like Barry’s “anti-Craft” language, are not “approaches” to making art when they are stated so baldly and with the intent to derrogate or exclude other approaches. At that point, they are just ways of policing the discourse community. And a strictly policed discourse community is not a fecund environment for great art — ask any anti-academic Modernist.

What I’d like to see is a more engaged recognition from within comics of the extent to which these ways of thinking about comics are schools or whatever that can co-exist and even overlap and inform each other. The “anti-Craft” approach Barry and others take is a school of cartooning and should be treated as such (someone mentioned James Kochalka’s term “cute brut” to me.) There is an “art school cartooning” that allows for naif narrative but requires more ambitious visual craft. I’m sure there are several more approaches that already exist within comics praxis, and there are definitely a number of approaches that hypothetically are possible but really do not exist within comics praxis.

If comics praxis is to expand to include the widest possible range of discourse communities in its scope — something which absolutely MUST HAPPEN before it can truly and accurately be considered a medium (rather than a genre) in praxis rather than in potential — comics practitioners, including critics, have to be able to talk about competing approaches as competing approaches, without bullying each other over the various ways that one approach excludes elements of the others. That’s the point of approaches — they select certain aspects to privilege and push aside others. But they do not do so universally — more comics like Eddie Campbell’s won’t mean there are fewer comics like Lynda Barry’s or Ariel Schrag’s or Seth’s. It will just mean the discourse communities who can find affinities with comics and make investments in comics will be bigger and more diverse, and that’s better for every cartoonist, no matter what his or her approach.