I grew up in a universe in which electrons were like planets orbiting double nuclei “suns” in tiny solar systems. It was a metaphor, a useful one at the time. Then new data required a figurative upheaval. Now the electrons of my children’s universe mingle in clouds. Electrons always have—chemistry teachers of my youth just didn’t know better. Any change in metaphor is also a change in reality. That’s why the in-between state, when the old system is collapsing but no new figurative principle has risen to organize the chaos, is so scary. Metaphors are how we think.

During the second half of the 20th century, the literary universe was a simple binary: good/bad, highbrow/lowbrow, serious/escapist, literature/pulp. Like Bohr’s atomic solar system, that model has lost its descriptive accuracy. We’ve hit a critical mass of literary data that don’t fit the old dichotomies. Margaret Atwood, Michael Chabon, and Jonathan Lethem are among the most obvious paradigm disruptors, but the list of literary/genre writers keeps expanding. A New Yorker editor, Joshua Rothman, recently added Emily St. John Mandel to the list: Her postapocalyptic novel Station Eleven is a National Book Award finalist—further evidence, Rothman writes, of the “genre apocalypse.”

Rothman resurrects Northrop Frye to fill the vacuum left by the collapsing genre system, but the Frye model’s four-part structure (novel, romance, anatomy, confession) is more likely to spread chaos (“novel” is a kind of novel?). Another suggestion comes from a holdout of the 20th-century model: The critic Arthur Krystal believes an indisputable boundary separates “guilty pleasures” from serious writing. Perhaps more disorienting, Chabon would strip bookstores of all signage and shelve all fiction together. Ursula Le Guin, probably the most celebrated speculative-fiction author alive, agrees: “Literature is the extant body of written art. All novels belong to it.”

I applaud the egalitarian spirit, but the Chabon-Le Guin nonmodel, while accurate, offers no conceptual comforts. The Bohr model survived even after physicists knew it was wrong because it was so eloquent. Even this former high-school-chemistry student could steer his B-average brain through it. A vast expanse of free-floating books is unnavigable. A good metaphor needs gravity.

To explain the lowly lowbrow world of comic books, Peter Coogan, director of the Institute for Comics Studies, spins superheroes around a “genre sun”—the closer a text orbits the sun, the more rigid the text’s generic conventions. It’s a good metaphor, which is why most models use some version of it, including all those old binaries: The further a text travels from the bad-lowbrow-genre-escapist sun, the more good-highbrow-literary-serious it is. But because metaphors control how we think, solar models are preventing us from understanding changes in our literary/genre universe. It looks like an apocalypse only because we don’t know how to measure it yet.

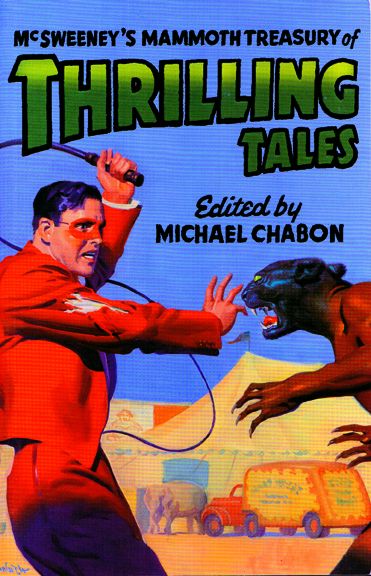

Chabon is often credited for starting the genre debate with “Thrilling Tales,” the first genre-themed issue of McSweeney’s, published in 2003—though the Peter Straub-edited “New Wave Fabulists” issue of Conjunctions beat it to press by months, and surely Francis Ford Coppola deserves credit for rebooting the classic pulp magazine All-Story in 1997. Coppola has since published luminaries like Rushdie and Murakami, even if, according to the old model, those literary gas giants should exude far too much gravitas to be attracted to a lowly pulp star. And what becomes of second-class planets when their own creators declare them subliterary? According to S.S. Van Dine’s 1928 writing rules, detective fiction shouldn’t include any “long descriptive passages” or “literary dallying with side-issues,” not even “subtly worked-out character analyses.” For Krystal, if a “bad” novel becomes “good,” it exits its neighborhood and ascends into Literature. The Krystal universe of fiction resolves around the collapsed sun of a black genre hole, and his literary event horizon separates which novels are sucked in and which escape into the expansive beauty of literary fiction.

Lev Grossman, author of The Magicians, calls that argument “bollocks, of the most bollocky kind.”

“As soon as a novel becomes moving or important or great,” he retorted in Time, “critics try to surgically extract it from its genre, lest our carefully constructed hierarchies collapse in the presence of such a taxonomical anomaly.” The problem is nomenclature. Grossman defines genre by tropes: A story about a detective is a detective story—it may or may not also be a formulaic detective story. Krystal defines genre exclusively by formula. Substitute out the ambiguous term, and his logic is self-evident: When a formula novel ceases to be primarily about its formula it is no longer a formula novel. Well, duh.

Grossman’s trope approach makes more sense, but Krystal is nostalgic for more than generic categorization. The old dichotomy was seductive because it was (as Grossman points out) hierarchical, performing the double organizing duty of describing and evaluating. By opposing “literary” to “genre” and then conflating “literary” with “quality,” Krystal is forced to make some ineloquent claims: “All the Pretty Horses is no more a western than 1984 is science fiction.” While technically true (Cormac McCarthy’s and Orwell’s novels are genre to the same degree), such assertions are forgivable as long as they are exceptions. But when those free-floating planets represent the expanding norm (in what possible sense are Atwood’s, McCarthy’s, and Colson Whitehead’s most recent novels not apocalyptic?), Krystal’s model collapses.

At least the good/bad dichotomy has collapsed. It never made categorical sense, since a “bad good book”—a poorly written work of literary fiction—had no category. Literary fiction is another problematic term. It traditionally denotes narrative realism, fiction that appears to take place here on Earth, but it’s also been used as shorthand for works of artistic worth. With the second half of the definition provisionally struck, we’re left with realism. Its solar center is mimesis, the mirror that works of literature are held against to test their ability to reflect our world. Northrop Frye declared mimesis one of the two defining poles of literature, though he had trouble naming its opposite. Frye located romance—a category that includes romance as well as all other popular genres (and so another conceptual strike against the Frye model)—in the idealized world, so Harlequin romances are part fantasy too (real guys just aren’t that gorgeous and wonderful).

But any overt authorial agenda can rile mimesis fans. Agni editor Sven Birkerts panned Margaret Atwood’s first MaddAddam novel because “its characters all lack the chromosome that confers deeper human credibility,” and so, he concluded of the larger premise-driven genre, “science fiction will never be Literature with a capital ‘L.’” Atwood was writing in a subliterary mode because she had an overt social and political intention. So her greatest literary sins, for Birkerts, aren’t her genetically engineered humans, but her Godlike and so nonmimetic use of them.

Others have tried to balance the seesaw with poetic style or formula or sincerity, suggesting that literature is a wheel of spectra with mimesis at its revolving center. In the old model, mimesis was also the definition of “literary quality”: The closer a work of fiction orbited its mimetic sun, the brighter and better it was. Like the Bohr model, that’s comprehensively simple, and so little wonder Krystal is still grasping it: Literature is the lone throbbing speck of Universal Goodness surrounded by an abyss of quality-sucking black genre space. Remove “quality” from the equation and posit a spectrum of mimetic to nonmimetic categorizations bearing no innate relationship to artistic worth, and the system still collapses.

Quality could rest in that fuzzy middle zone, a literary sweet spot combining the event horizons of two stars: mimesis and genre. That middle way is tempting—and perhaps even accurate when studying “21st Century North American Literary Genre Fiction,” the clumsily titled course I taught last semester. I am requiring my current advanced fiction workshop students to write in that two-star mode, applying psychological realism to a genre of their choice. But it’s a lie. If quality is mobile, and it is, then no position on the spectrum—any spectrum—is inherently “good.”

Perhaps novels, like the electrons of my youth, orbit double-star nuclei, zigzagging around convention neutrons and invention protons in states of qualitative flux. It’s not just the text—it’s the reader. That’s a central paradox of physics too. “We are faced with a new kind of difficulty,” wrote Albert Einstein. “We have two contradictory pictures of reality; separately neither of them fully explains the phenomena of light, but together they do.” Light, depending on how you measure it, is made either of particles or of waves—and so somehow is both. That seemingly impossible wave-particle duality applies to all quantic elements, including works of fiction.

The cognitive psychologists David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano, in their 2013 study, “Reading Literary Fiction Improves Theory of Mind,”dragged the genre debate onto the pages of Science. Literary fiction, they reason, makes readers infer the thoughts and feelings of characters with complex inner lives. Psychologists call that Theory of Mind. I call it psychological realism, another form of mimesis. The researchers place popular fiction at the other, nonmimetic pole, because popular fiction, they argue, is populated by simple and predictable characters, and so reading about them doesn’t involve “ToM.”

Kidd and Castano are recycling Krystal’s “genre” definition, only using “popular” for “formulaic.” Their results support their hypothesis—volunteers who read literary fiction scored better on ToM tests afterward—because their literary reading included “Corrie,” a recent O. Henry Prize-winning story by Alice Munro, and the genre reading included Robert Heinlein’s “Space Jockey,” a detailed speculation on the nuts and bolts of space travel populated by appallingly two-dimensional characters. The science is as circular as Krystal’s: Stories that don’t use readers’ ToM skills don’t improve readers’ ToM skills.

If psychological realism is taxonomically useful for defining “literary” (and I believe it is), then here’s a better question: What results would a ToM-focused genre story yield? My colleague in Washington and Lee University’s psychology department, Dan Johnson, and I are exploring that right now. For a pilot study, we created two versions of the same ToM-focused scene. One takes place in a diner, the other on a spaceship. Aside from word substitutions (“door” and “airlock,” “waitress” and “android”), it’s the same story, the same inference-rich exploration of characters’ inner experiences. When asked how much effort was needed to understand the characters, the readers of the narrative-realist scene reported expending 45 percent more effort than the sci-fi readers. The narrative realists also scored 22 percent higher on a comprehension quiz. When asked to rate the scene’s quality on a five-point scale, the diner landed 45 percent higher than the spaceship. The inclusion of sci-fi tropes flipped a switch in our readers’ heads, reducing the amount of effort they exerted and so also their understanding and appreciation. Genre made them stupid. “Literariness” is at least partially a product of a reader’s expectations, whether you lean in or kick back. Fiction, like light, can be two things at once.

This wave-particle model may or may not emerge as the organizing metaphor of contemporary literature, but follow-up experiments are under way. We will survive the genre apocalypse. In fact, I predict we’ll find ourselves still orbiting the mimetic sun of psychological realism. The good/bad, literary/genre binary has collapsed, but the center still holds.

[This article originally appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education in January 2015.]